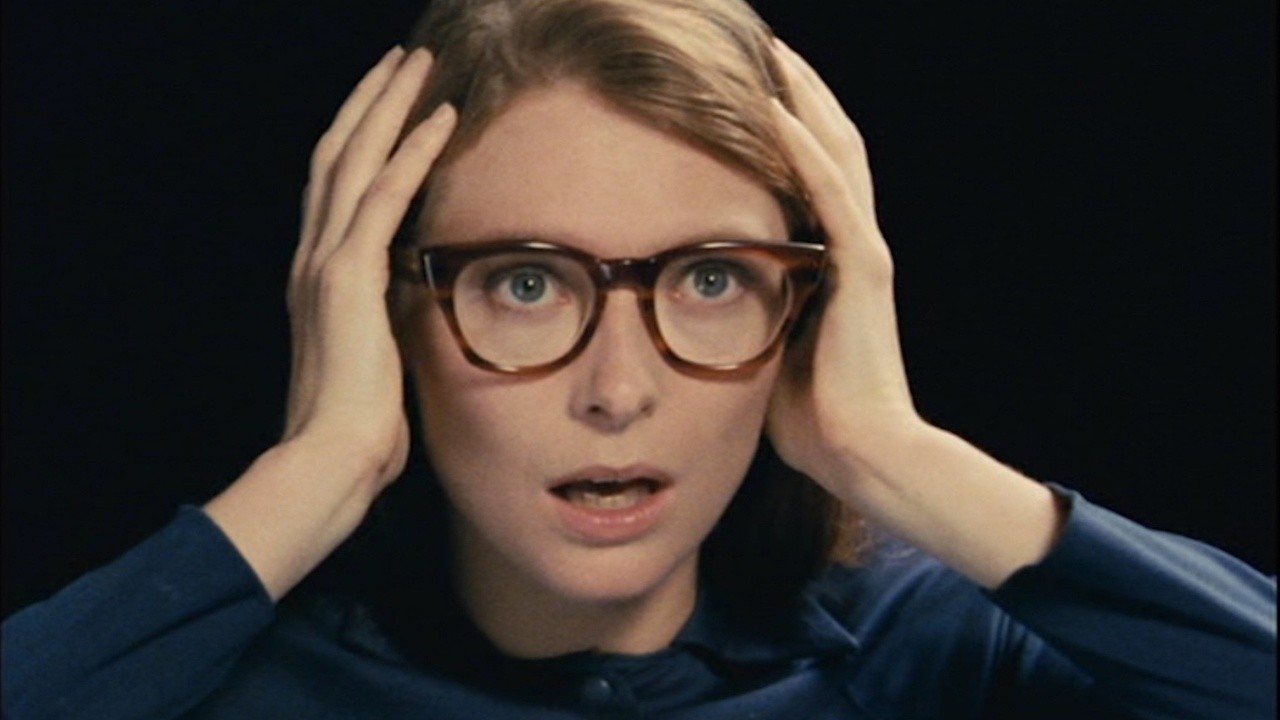

Few veteran filmmakers have had a more sudden ascent to acclaim than Joanna Hogg. Most would have come to have known her through her magnificent The Souvenir duology, which won her many new admirers. For those with an ear to the ground in terms of British independent cinema, she would be familiar as the director behind small but well-received dramas like Archipelago and Exhibition, which were celebrated in small but substantial groups of devotees to alternative cinema. However, she has steadily been growing in esteem, having something of a second-act to what is already quite a fascinating career. Recently we saw Caprice, her thesis film from when she was a young student, being given a release, and it’s not difficult to see exactly why Hogg would go on to become one of the more interesting directors working in British independent film. The project, which is a 27-minute long experimental short film, sees the first collaboration between the director and one of her muses, the incredible Tilda Swinton (here credited under the full name “Matilda”, an obvious but still disorienting detail that proves what a very early work this was in both artists’ careers), and tells the story of young woman obsessed with a particular fashion magazine being transported into its pages, where she navigates a peculiar version of the world that has captivated her for years, encountering the individuals she has read about, and discovering that there is a downside to fame that isn’t accurately represented in the glamorous world of fashion and entertainment publications, which work together in forming this dreamlike, surreal voyage into the world of pop culture and our collective obsession with it.

Needless to say, Caprice proves that old adage that the most dynamic products come in the smallest packages – and in a film that barely runs half an hour, Hogg manages to dive deep into some very potent issues, all filtered through the lens of postmodernism, which seems to have informed much of this film’s creation. One of the movement’s central tenets is that it is all about deconstruction, and Caprice proves itself to be aligned with similar ideas, quite literally seeing the protagonist venture into a fantastical world, where the magazine that has been the subject of her adoration is suddenly surrounding her, Hogg pulling apart the layers to reveal the message embedded deep within the story, which isn’t all that clear at first. At a cursory glance, we’d likely believe that Caprice is a work of self-indulgent ambition from a young and audacious filmmaker who had to produce something to meet the requirements of her university course (and thus we should appropriately scale or criticisms and perceptions based around the fact that it was never intended for wider distribution, especially not over a quarter of a century later), and in many ways, this is exactly what it is. However, looking beyond the very obvious, and instead focusing on the intention, we can soon discover that this short film is actually a much more captivating work than many would give it credit for, a daring and provocative exercise in metafictional filmmaking that understands the constraints, not only of the storytelling process, but also of the subject matter that forms the foundation of the film that surrounds these bold ideas.

Throughout the short but impactful running time of Caprice, there are unmistakeable traits that place this within the realm of novice filmmaking (referring to it as “amateur” is not only inappropriate, it’s entirely wrong – Hogg had amassed quite a bit of experience through her studies, as evidenced by this film’s very unique tone and appearance). The most obvious sign is the use of film sets, where this entire adventure takes place on a single stage, with only the backdrops changing to indicate a shift in location. Naturally, this is the result of Hogg and her collaborators being a small group of penniless students tasked with making a film without much of a budget, or any of the luxuries industry professionals take for granted. Fortunately, this very simple execution allows the film to take on an artificial appearance, which services the story well, the gaudy sets and clearly second-hand or homemade costumes lending the film a very distinct charm, the kind that formed the foundation of many early independent films, which were rarely produced to make money, but rather for other purposes, such as for a school project. Caprice proves that one doesn’t need anything other than ambition and a group of like-minded collaborators to make something special, and the “do-it-yourself” aesthetic actually services the film and adds accidental nuance to the story, which benefits massively from the small-scale production. This is one of the rare cases where an early short film is perfectly acceptable the way it is, rather than being used as a way to experiment with the form and acting as a placeholder for a feature film adaptation later on, where the story is expanded (as we often see with directorial debuts). Standing entirely on its own, Caprice manages to be just as inspiring and gripping as films three or four times its length, which is not an easy feat to accomplish.

As the first thesis film reviewed here, it was a challenging experience to watch and write about Caprice, since it’s unfair to assert the same discerning perspective on a film that was not intended for such purposes. However, there wasn’t any need to hedge expectations or soften the approach taken in writing about it, since this is a perfectly decent and inspiring work of independent filmmaking that immediately proved that Hogg had a monumental future ahead of her. If there is one fact that becomes increasingly clear as we venture through this world, it would be that Hogg would never be a conventional filmmaker – she’s far too free-spirited in her perspective, and experimental in the approach she takes to telling stories, to ever play by the rules. Yet, this is something that is continuously celebrated as the sign of a great filmmaker, and even in something as small as a student short film, Hogg proved her mettle as a fascinating artistic voice, paying tribute to Technicolor musicals and vivid adventure films in this unconventional postmodern odyssey. It’s wonderful to see her receive so much acclaim for her work, to the point where the release of her thesis film feels like a major event, the unearthing of a lost project that proves, even at its most raw and inexperienced, she had a wealth of talents that could transform even a small student project into a fascinating and insightful work of fiction. Peculiar but memorable, and incredibly well-made considering the constraints she had to work with, Caprice is a unique and fascinating glimpse into the young mind of one of the finest, yet sadly mostly unheralded, filmmakers working today, and who we are mercifully seeing receive the acclaim and admiration she was been overdue to receive for several years now.