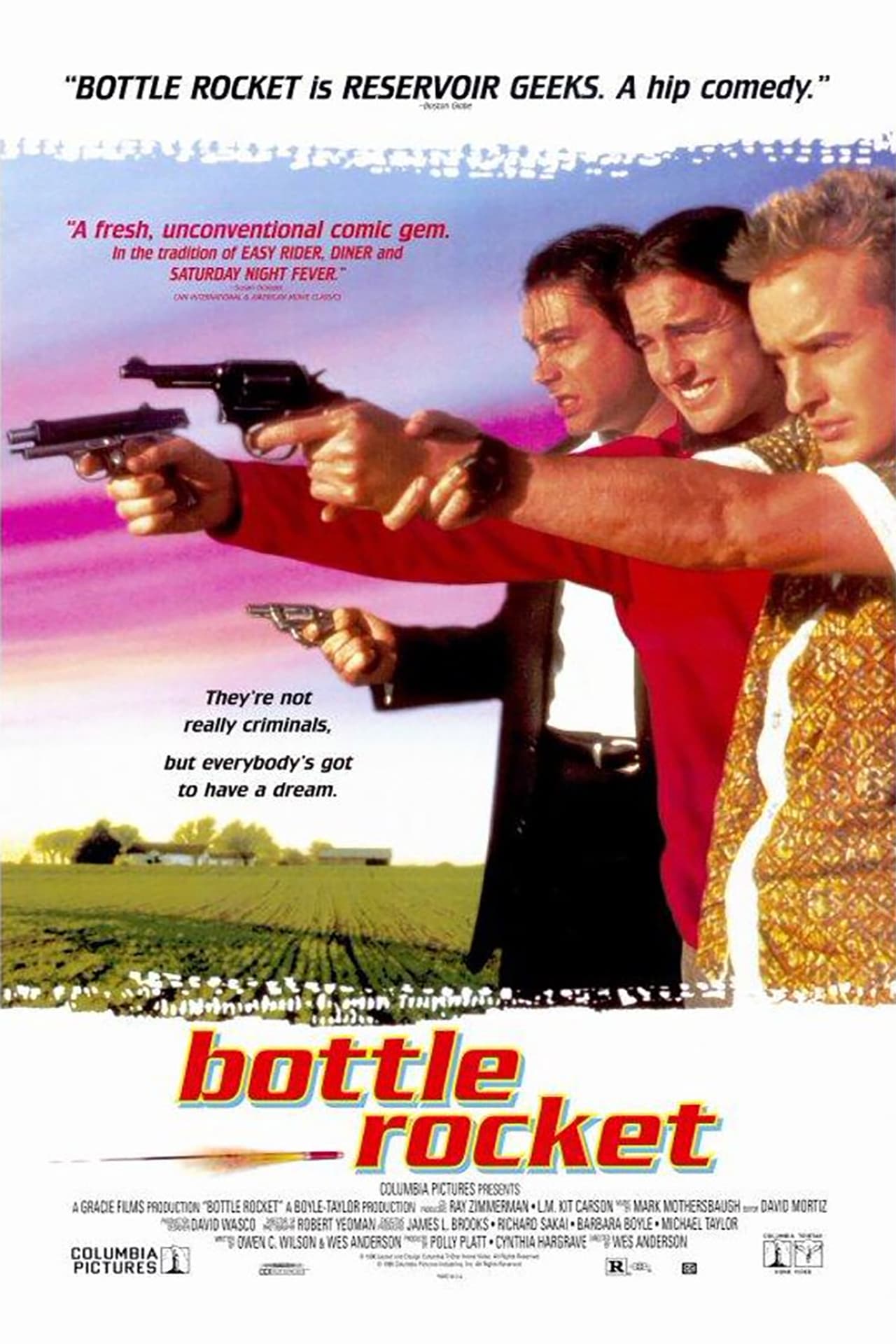

While he remains quite a popular figure, Wes Anderson has had his fair share of polarizing reactions, with his recent work indicating that he is a director with a penchant for the quirky and overly-stylised, which has amounted in him receiving an equal share of devotees and detractors. I fall between the two – I admire him as an artist, but find that he is gradually collapsing into his own idiosyncracies, becoming too focused on style and not providing enough substance to some very interesting stories. This is a more recent development, since looking all the way back to the beginning of his career affords us a chance to see a very different kind of director, as made evident by Bottle Rocket, his directorial debut and a film that bears some of the esteemed filmmaker’s most notable quirks, but also represents a more rough and personal approach to his filmmaking style. It might be more intimate, and focused on a smaller group of characters (as well as a much more simple story), but Bottle Rocket is still quintessentially the work of a director who has continuously pushed the envelope from his first time behind a camera. There’s an argument to be made that this may be amongst his finest achievements, if only for the sake of it being so radically different from anything he did afterwards (even if one absolutely admires Anderson, it’s difficult to not be fascinated by the clear differences embedded in this film and in his later work). This argument is almost always dismissed based on the virtue that this was a very early attempt to venture into the world of filmmaking, and thus Anderson’s style was still a work-in-progress – but without the risks he took in adapting his shoestring-budgeted short film into a feature-length production, none of his other works would’ve been possible, since this one set the foundation and allowed for the director to pursue new opportunities that formed him into the artist he is today.

The qualities that make Anderson such an inventive artist are not difficult to understand – like some of his contemporaries, he’s developed a style that he can easily adapt to any story, spinning tales in any corner of the world, focusing on any kind of character, and still giving a clear indication that this is one of his films. His quirky style can be an acquired taste, but it’s one that has been relatively well-celebrated, even by those who aren’t entirely sold on his peculiar stylistic choices. Bottle Rocket, contrary to what some may say, isn’t entirely deviant from this style – it is a more experimental comedy, but the traces of Anderson’s work is very clear. Whether it be in the camera movements (with the distinctive static shots), production design or off-the-wall characters, this is still very much the incubator for the director Anderson was set to become. Set in his native Texas (and thus having some degree of self-referential qualities, as he’s clearly drawing from his own youth), and telling the story of a group of mischievous young men with ambitions that extend far beyond their small southern hamlet, this is clearly a work that is very close to the heart of the director, as well as his two stars, Owen Wilson (who co-wrote the film) and Luke Wilson, both of whom are giving breakthrough performances as the dim-witted but kind-hearted Texan slackers who just want to make something of themselves. There’s something about a debut film that sees a director reflecting on their own life (even if not telling a directly autobiographical story), that keeps us engaged, since it feels like Anderson is giving us unrestrained insights into his own life – and considering he’s a director that has often been accused of high-concept storytelling that lacks a particular viewpoint (which is often replaced with his very distinct authorial voice), Bottle Rocket is perhaps his most daring project, at least in terms of telling us who the director is, and where he comes from.

If there is one quality that persists throughout Anderson’s work, regardless of the story, it’s the abundance of heart, which is the major reason why it’s so entirely difficult to criticize his work, since even at its most unbearably twee, they tend to resonate, being well-formed examples of incredible emotion. Bottle Rocket certainly doesn’t skimp on this aspect, and is in many ways one of the director’s most emotional stories – it centres on three friends trying to navigate their way out of their small town, doing it through planning a series of small heists that they believe will bring them fame and fortune, not realizing that they aren’t criminal masterminds, but rather a trio of misguided youngsters that may have an abundance of ambition, but lack a clear sense of direction. At his best, Anderson is an incredible social critic, since looking beyond the stylish nature he often employs in his films, his stories focus on the relationships between people as they try and overcome some particularly challenging situations. This is the most common thread that persists throughout his filmmaking career , alongside the very real emotion that underpins these stories, and they help make his directorial ventures all the more enriching, since there is real depth to these people. When you set aside the very endearing comedy, you’re likely to find that Bottle Rocket is a rather sad film, a melancholy tale of the fleeting days of youth. Not many people could make a film that is essentially 90 minutes of two grown men acting like teenagers, and have it come across as entirely endearing and beautifully poignant – but for all his faults, if there is something that Anderson has mastered by this point, it’s that he knows how to tell a compelling story about human connections, which is the fundamental basis of Bottle Rocket.

Anderson is helped along wonderfully by his cast, and even from the first time he directed a film, he demonstrated a keen understanding on how to bring out memorable performances. Owen Wilson and Luke Wilson have had wildly popular careers, but neither has ever been better than under the direction of their friend Anderson, who wrote them two star-making characters in the roles of Dignan and Anthony, two wayward young men who are doing their best to look beyond the neatly-trimmed lawns of their Texas town. For them, hope resides on the other side of the horizon, but they don’t realize there is no shortcut to a prosperous future. Both of the Wilson brothers are wonderful – they’re able to play such different characters, in both temperament and capacity to be rational, while still fitting perfectly into this world. Anderson may have accumulated a wide range of regular collaborators over his career (each new film seems to bring in another few fantastic actors), but his fondness for the Wilson brothers, who were as pivotal in launching his career as he was theirs, is clear from the first moment they appear on screen. The legendary James Caan appears in the third act, and while he only has a handful of scenes, he is clearly having a lot of fun in the role of a part-time criminal, full-time landscaping tycoon – it’s quite surprising how Caan hasn’t appeared in any of Anderson’s later films, since he had the exact kind of manic energy that the director is able to harness so beautifully. It’s inarguably a smaller ensemble, but it’s one that is filled with vivid and distinct characters nonetheless, which only helps us situate this within the wider universe of the director’s diverse career.

It’s difficult not to love Bottle Rocket – this is the kind of film that compensates for its relative immaturity (an intentional choice based on the kinds of characters at the heart of the film), with an abundance of emotional resonance, which helps guide us through this off-kilter world. Anderson is having a lot of fun here – the story itself isn’t particularly serious, and it evokes a sub-genre of independent films from the 1990s and early 2000s that were less focused on an individual story, and more on establishing a specific atmosphere, in which a bevvy of quirky and eccentric characters luxuriate. The director doesn’t waste any time – every moment in Bottle Rocket is genuinely endearing, and there’s a kind of uniqueness to the storytelling that feels rich and evocative. It may not be the artistic achievement that we’d come to expect from Anderson later on in his career, but it’s certainly just as wonderfully warm and charming, especially when it comes down to the aspects that really matter. He doesn’t always succeed wholeheartedly at taking these bold leaps, but when he does (which is most of the time, with only a few small missteps throughout his career), Anderson is capable of absolute magic. It’s a wonderfully unique and delightful comedy about friendship and individuality, and through the lovable performances by the two leads, a strong story and a very precise and meaningful execution, the film evolves far beyond just a silly comedy, becoming something much more special by the end.