The title The Green Man might not be familiar to many viewers, who might (on hearing of it), expect it to be some strange, provocative science fiction thriller, since it evokes such images, as well as being made during an era where these films were at their peak. However, in reality, the film is a deranged and absolutely brilliant dark comedy focusing on a freelance assassin who has his most recent assignment derailed when a young vacuum cleaner salesman and a young woman he has just met stumble onto his plans to murder a well-known public figure. Robert Day and Basil Dearden (the latter having co-directed this film without receiving a credit) made something profoundly strange, but also incredibly enticing – complex, but beautifully executed, The Green Man is a wonderful film, the kind of obscure gem that only becomes more effective as a piece as more audiences discover it. In recent years, it has gradually started to be seen by a wider group of viewers, all of whom find themselves utterly engaged with this bewilderingly strange story of an assassin having his biggest job foiled by the presence of two incompetent pedestrian citizens who stumble onto his plot by accident – and through all of the madness emerges a rivetting, hilarious irreverent comedy-of-manners that focuses on the social aspect in a way that many films at the time refuse to, as it was considered too absurd to actually expect audiences to relate to what we were seeing on screen. Yet, The Green Man presses on, and occupies its own unique space in the culture as a bewilderingly entertaining film about how the tiniest of mistakes can lead to enormous complications that are sometimes literally a matter of life and death, as proven here.

There is something about British comedy just after the Second World War that are so captivating – the influence of Ealing Studios over the development of British humour around this time played a substantial role in exposing the inherent comedic side of society, focusing on deconstructing the unwritten social and cultural laws, and taking aim at the peculiarities of the country and its occupants. However, the war naturally brought a cynicism to the proceedings (we see this occurring in the national cinemas of all the major countries that were involved in some way, a reflection of the loss of optimism, and the need to be more critical and introspective about how it conveys its culture). On one side, there were the “angry young men” that started to emerge around this time, and on the other, the more renegade, comedically-minded folk who were more focused on bringing out the humour in these terrible circumstances. The Green Man certainly fits into this category, and the directors ensure that every frame is brimming with an off-kilter energy that hints at something deeper and more profound, without becoming heavy-handed in its themes. Day and Dearden were invested in pulling together a fascinating story that provoked thought and extracted laughter – and layering on an overriding plot about an assassin taking aim at his next victim may seem like an odd choice for a film designed under the manifesto of boosting national morale, yet it all makes absolutely perfect sense when taken in context, and executed with the delightful irreverence for authority that we can see scattered throughout The Green Man, a film that doesn’t seem to mind too much about courting controversy, as it has bigger intentions than playing by the rules, which is nothing if not admirable.

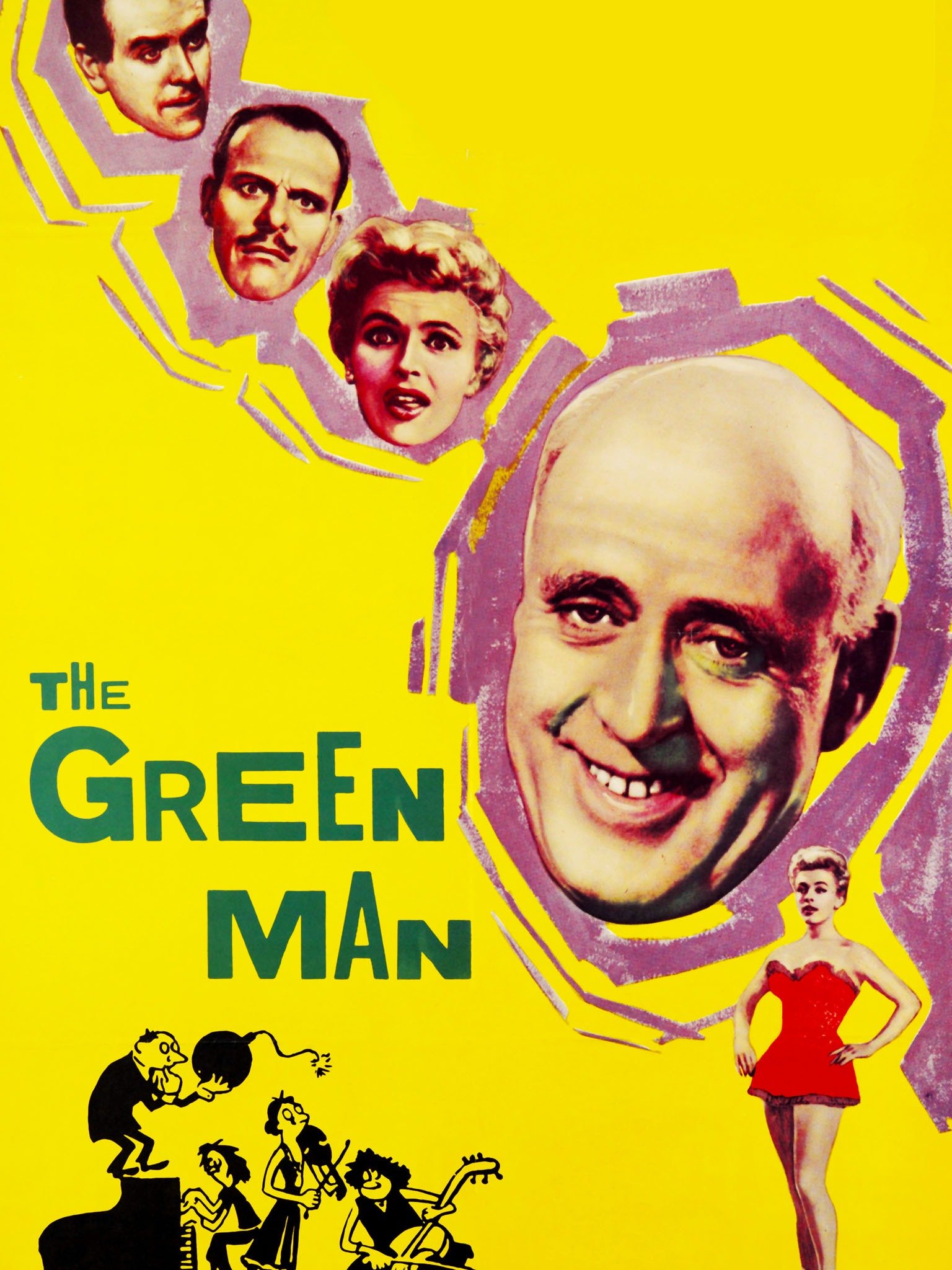

The combination of a “stiff upper lip” British comedy-of-manners that pokes fun at social mores, with a pitch-black satire centred around someone who literally makes a killing from killing people serves to be quite a peculiar approach to making a film, but as we’ve seen with many other films produced at this time (particularly in Great Britain – what is it about the British that attracts them to such dark and bleak stories?), there is merit to extracting humour from darker material. The directors of The Green Man find the perfect balance between the horrifying subject matter and the blasé, almost even flippant, humourous approach to exploring it. Part of the success comes in the presence of two titans of British comedy, Alastair Sim and Terry-Thomas, both of whom are anchors of this particular era of comedy, and are always welcome additions to any film. Their participation may be limited to major supporting roles (despite Sims playing the de facto anti-hero for much of the film), but the fact that they lent their talents to this film in the first place grounds the story and makes it much more endearing, as opposed to casting more serious actors who may not have found the humour in the characters. The script is also structured very interestingly – there is a central plot, but the film mainly consists of a series of extended vignettes, all centred around something relating to the main premise, until the final act, where everything converges into a dizzying, chaotic array of hilarious errors that may induce stress in the viewer, but in a way that actually feels entertaining, since tension is a powerful tool when used correctly. All the components for a wildly successful film can be found scattered throughout this film, which feels all the more enthralling considering the effort that went into making it as entertaining as it could be with such a dark story at its centre.

The Green Man may not be particularly funny compared to other films from this era, but its merits are found in how it balances the humour with a more sobering set of conversations. It may be entirely understandable by this film has resided in relative obscurity for all these years – it’s not the most exuberant of comedies, and the jokes don’t always land. It’s not all that different from your garden variety dark comedy that tended to come about as a response to the growing cynicism of a world undergoing considerable change – but beneath all of this, there is a very charming film that set out to enthral audiences with a joyful and entertaining story with overtures or romance, just so happens to be centred on someone whose career hinges on his ability to murder people without much suspicion. A somewhat revolutionary work in terms of the discussions it evokes, and how it played a part in establishing dark comedies that dare to focus on more harrowing subject matter – it’s not the defining work in this regard, nor is it one that necessarily lends itself to vast discussions. Yet, it is still a wonderfully unique film, beautifully made (it has that elegant style that is indicative of this era in British cinema), and runs at a brisk 80 minutes, so even if the main takeaway from the film is its message, the delivery is, at the very least, enthralling enough to keep us interested, which is more than enough to justify some of the liberties taken throughout this wonderfully strange and unique piece of darkly comical cinema.