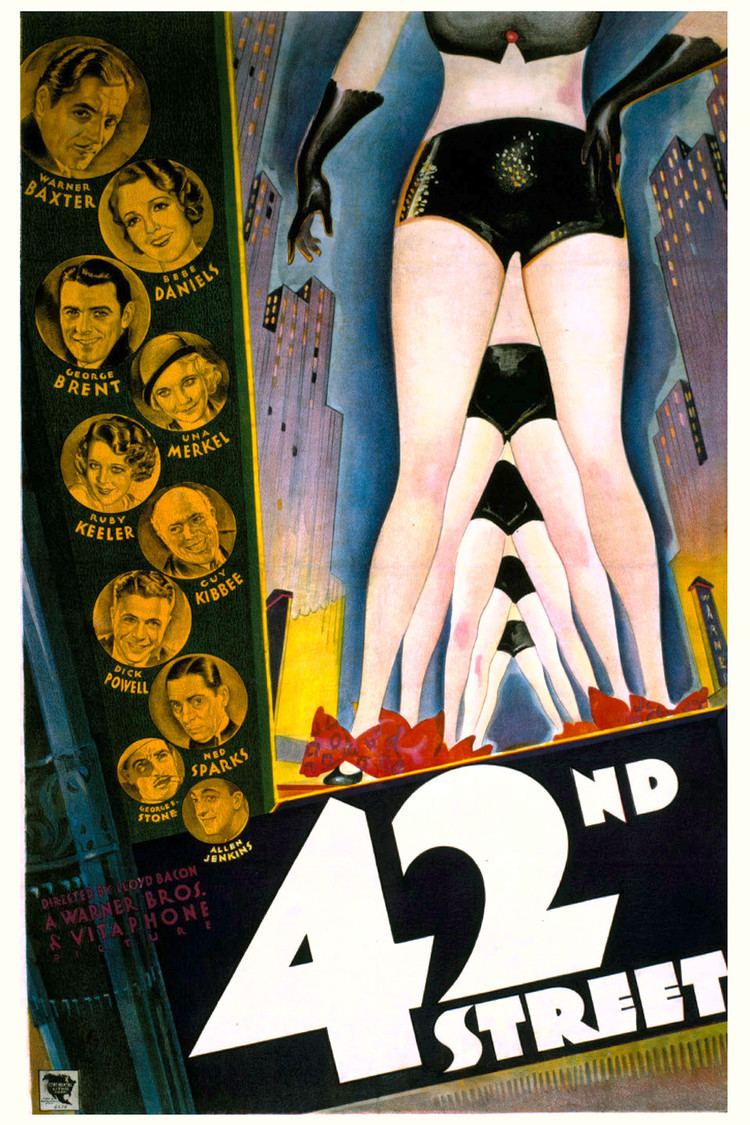

When it comes to musical films, there often exists two completely different entities – the concept and the execution, with many of them focusing on one over the other, in addition to varying quality of the music involved. There are a few that manage to combine both beautifully, but they’re slightly more rare, often restricted to only a handful of masterful musicals that work both elements into the filmmaking. 42nd Street is one of the most legendary screen musicals ever made, an early Pre-Code drama that serves as a revolutionary glimpse into the rise (and inevitable fall) of a Broadway musical. Directed by the curiously talented Lloyd Bacon, who takes the script by Rian James and James Seymour and concocts pure visual splendour out of a relatively simple storyline, and anchored by wonderful performances by the likes of Warner Baxter, Bebe Daniels and Ruby Keeler, 42nd Street has more than established itself as a great film – it’s an essential work of cinema, a daring and provocative journey behind the theatre curtain and right into the heart of the myriad of people who are tasked with bringing a major production to life – a gruelling but captivating drama that has hints of wonderfully effervescent comedy embedded at its core (mainly the result of the very human element that drives the film forward), 42nd Street has its work cut out for it, and it achieves exactly what it aimed to accomplish, gradually revealing as much as the entertainment industry as it did the people involved.

This film is the final result of the combination of many different moving parts, all brilliantly assembled by a director who had a great deal of experience mounting ambitious production. Bacon may not be a director that is often revered as much as some of his contemporaries, but he had an inspiring level of audacity that is worth noting. A director whose origins were in the pioneering days of the silent era, directing everything from Charlie Chaplin shorts to early western action films – and as a result, he was an artist who understood movement and expressivity more than many of his peers. The Pre-Code era was defined by stories that pushed the boundaries, and while there is nothing particularly controversial about 42nd Street (outside of a brief inference towards homosexuality, in a moment that is more comedic than anything else), there is a sense that the filmmakers were actively pursuing something deeper than the widely-embraced, crowd-pleasing musical comedies produced around this time. The transition between the silent and sound era gave many directors the opportunity to extend their art, especially those that focused on the convergence of music and performance – so for a film like 42nd Street to come about in such close proximity to this change, and still be willing to have some very deep conversation about the realities of the entertainment industry, is absolutely fascinating, and is one of the components of 42nd Street that is most compelling and worth discussion.

This is precisely where 42nd Street is at its most captivating, since even though it was a very quaint and endearing musical comedy at a time when these kinds of stories were very popular, it is never solely defined by this, and functions as one of the pioneering “backstage” dramas, giving us invaluable insights into the affairs that happen behind the scenes of a major production. This kind of story, at least in this form, was absolutely unprecedented. Bacon offers valuable insights into the trials and tribulations of the cast and crew of Pretty Lady as they plan to mount an enormous performance of a new musical, in the hopes that it’ll ignite the career of the young stars, give an opportunity to those in the chorus, be an enormous success for the scrappy young writers and allow the director to retire comfortably – and throughout the film, emphasis is placed less on the production as a whole, and more on the individual components, the people involved in its creation. Bacon beautifully deconstructs the concept of a musical with this film, giving us access into the lurid scandals and mild controversies that fuel nearly any production, cleverly withholding the spectacle until the very end, when it finally converges into a stunning climax that stands as one of the most interesting uses of the musical film format ever captured, a doubly impressive achievement considering how this was still a relatively new approach to storytelling. The details are captivating, but never distract from the growing tension that revolves around whether or not we will get to see this supposedly ambitious production – and the two themes working in tandem are exactly what allows 42nd Street to transcend genre and convention in its pursuit of some deep, thematically-rich storytelling techniques.

Occasionally, we encounter a piece of filmmaking that evolves into the kind of art that it is critiquing – and the concept of a major stage musical being at the heart of 42nd Street eventually turns into the final few scenes, where we finally see the bold and ambitious production that has been the subject of the previous hour come to fruition. If there was anyone that could capture the manic, inspiring chaos that comes with such a production, it’s Busby Berkeley, one of the great choreographers to ever work in any medium. This is the exact moment when Bacon takes a few steps back and allows the film to become entirely the property of Berkeley, with the director’s responsibility suddenly less of him shepherding the story forward, and instead making sure he captured every detail in the esteemed dancer’s process. The camera movements are fluid and profoundly modern – somehow, Bacon and Berkeley are working in tandem to bring this production to life. This is the epitome of a breathtaking climax – the entire film was leading up to this very moment, and while there were some memorable sequences, it’s only when we (like the audience in that Broadway theatre) get to encounter the actual production, that we understand how impactful a piece of art 42nd Street actually is.

When Ethel Merman (and many others over the years) sang those resounding words “there’s no business like showbusiness”, one has to wonder whether this film inspired those lyrics – and while it is obviously unlikely, that kind of rapturous celebration of the experience of simply performing is very much a part of our collective culture. 42nd Street is one of the greatest examples of this kind of storytelling – a detailed account of a major production, and the people who appear on both sides of the curtain, focusing on the many challenges they endure while trying to mount what could be the most important show of their lives. In this film, the stakes are high and the tensions even higher – and Bacon pulls together quite a formidable cast to interpret this strong story, which pays tribute to the heyday of Broadway, and the countless people that have made their way through those hallowed halls, not to mention the many more than never got the opportunity. Beautifully-made, and propelled by a real sense of generosity for its characters and the world they occupy, 42nd Street is an absolute triumph, and a worthwhile entry into a strong canon of early musical films that not only offered entertainment, but provoked some decent, meaningful conversation as well along the way, especially on the subject of fame and ambition.