What is most fascinating – or perhaps even bewildering – about Bigger Than Life is the fundamental duality at its centre that creates something of a contradiction, since it is simultaneously a poignant product of a particular era, while still be truly ahead of its time. This kind of paradox is often found in the work of Nicholas Ray, a director who reigned supreme in the final waning years of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and proved himself to be someone who could weave together the most fascinating portrayals of humanity from the most simple material. His adaptation of “Ten Feet Tall”, a widely-circulated medical article turned out to be one of the finest melodramas of its time, a dark and brooding tale of a descent into madness, anchored by a towering performance by one of the most impressive actors of his generation, whose touch is found everywhere in this film. Bigger Than Life is an astounding work of socially charged fiction, the kind of film that forces us to stop and reconsider our own choices, while peering voyeuristically into the life of a man whose entire existence is hanging by a slender thread, ready to fall apart at a moment’s notice. Far from the overwrought “message films” that were often just thinly-veiled parables, and more of a complex, human drama with an alarming social message at its core, Ray’s film is an impeccable achievement, a work of art that requires the viewer to become adjusted to what we’re seeing on screen, but rewarding anyone who surrenders to the unsettling storyline, since beneath the excess resides a bold and unforgiving social thriller that says more about our place in the world than perhaps any other similarly-themed film from this particular era ever could, which immediately makes this a film worth seeing.

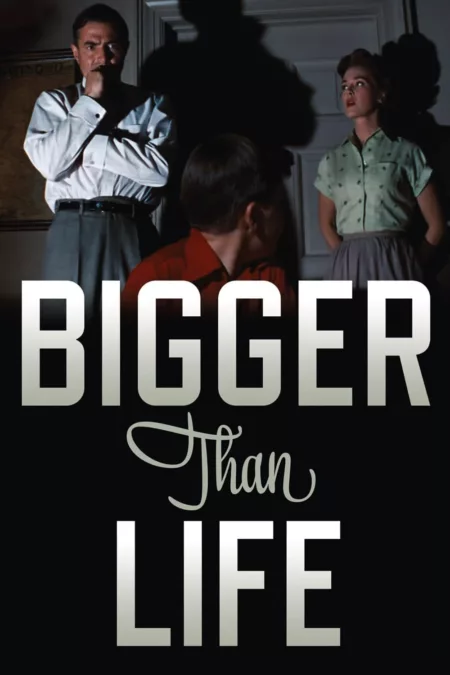

James Mason was an enigmatic actor – the consummate professional who was willing to take on any role, he often struggled to disappear into his parts unless it was one written to make use of his peculiar charms. Bigger Than Life was a passion project for Mason, since he not only co-wrote the film with Cyril Hume and Richard Maibaum, he served as the primary producer, and as a result played a pivotal role in forming this character, and defining how he was going to play the role. Mason inhabits every recess of Ed Avery – his posh diction, upbeat personality and debonair composure in both personality and physicality contrasted sharply with the deeper aspects of the character, especially as he descends into a life-changing addiction. Mason commands the film, and even when attention is diverted to some of the supporting cast (in particular Barbara Rush and Christopher Olsen, as his worried wife and curious son respectively, or Walter Matthau in an early role as Ed’s best friend), we can’t help but have our attention drawn back to Mason’s stunning performance, which towers over many others from this era, for the sole reason that it isn’t one that tries too hard – it understands what it is aiming to convey, and Mason gets into the mind of the complex anti-hero, a man who sees the world in various shades of desire, not for carnal satiation, but rather the craving something that he knows will be harmful to him, but yet he persists. It results in a stunning portrait of a man being driven mad by addiction, and truly functions as one of Mason’s peaks as an actor, especially in how it gradually peels away the layers of a man who fell victim to the spectre of addiction.

Self-destruction is a challenging topic, but it’s one that forms the centrepiece of Bigger Than Life, since it functions as a morality tale about the pratfalls of addiction. In this film, the vice is cortisone, a highly addictive hormone that was still used mainly in experimental studies. However, despite the drug of choice, the film still works as a powerful ode to the dangers of addiction, in the same way as The Lost Weekend and Days of Wine and Roses warned against the growing dependency on alcohol, and how it can not only impact someone’s own wellbeing, but impact their entire family, having an indelible influence on one’s domestic life. As mentioned previously, this film is radically ahead of its time, and even only in theory, Ray was doing something here that was worth a look. The film combines two pressing issues that are still very much relevant today (perhaps even more so now, since we continue to make new discoveries towards the human mind), insofar as it is about the tragic intersection between a growing drug addiction, and mental illness, something that was simply not spoken about often (with the only representation of such issues being unequivocally negative, and perhaps even warranting of a punishment). Bigger Than Life feels so refreshing because it comes across as genuinely caring about its subject, and even when it is at its most openly cynical, there is something beautifully poetic about how Ray frames the central dynamic, drawing out the positives, which he then sharply contrasts with the darker reality underpinning these happy moments. It’s a striking indictment on addiction, but not one that reviles the subject – after all, the character of Ed may act erratically and perhaps even unfairly, but he was ultimately a victim to a disease from which he found it difficult to wrangle free, so Ray’s method of showing the reality of addiction, without losing the compassion, makes for a beautifully empathetic work of art.

There’s a thought that strikes the viewer as they work their way through Bigger Than Life – not only is this film an incredible work of socially charged filmmaking, it’s an essential piece of American art, a document of a generation lost to the ambiguities of the twentieth century, victims of progressive medicines and new ideas that would take decades to become fully-consolidated in the culture. The American Dream is a motif that has been explored to the extent of being overused, a trope that is more of a burden to most films than it is a guiding concept. Yet, while it may not be so obvious, Bigger Than Life certainly does meet the primary criterion, namely in being bold enough to show that life under the American Dream is far from ideal. Set in the Eisenhower era, which we have been conditioned to believe was the finest period in recent American history (since they had been triumphant in the Second World War, and once again regained their place as a worldwide power), the film doesn’t so much explore the concept of a nuclear family so much as it actively attacks it, showing the flaws that come about when we rely on the idyllic, Rockwellesque image of the proverbial “perfect family”. The film is driven by a narrative focused on addiction, and while it makes some meaningful remarks on the psychological toll substance abuse can take on the addict, the most profound meaning comes about through how it impacts the family, and how they have to grow and adapt to the changes, which they fear may become a regular feature of their daily lives. Far from heavy-handed, but still hard-hitting, the domestic aspects of Bigger Than Life, and its ability to deconstruct the family unit in a way that feels authentic and far from forced, is incredibly potent and helps guide the film along to reach a truly harrowing emotional crescendo that perhaps defines the entire story.

Bigger than Life is a truly challenging film, and it gradually becomes quite a shocking exploration of addiction, one that is far more profound due to its unconventional nature of looking at how an over-dependence on some substance can not only drive someone beyond the point of sanity, but also have an enormous impact on their lives, tearing their domestic life apart while making changes to their own worldwide perspective. It’s not an easy film, and it can sometimes come across as quite callous – part of this comes from James Mason’s incredible performance, since he manages to find the right balance between a character we sympathize with, and someone whose behaviour is so abhorrent, it comes close to being irredeemable. It’s a beautiful film, but one that dares the audience to look deeper into their idea of what constitutes a perfect family – Ray avoids sentimentality, but ensures that he is still showing the darker side of the idealistic image of suburban bliss, since below even the most well-adjusted, seemingly perfect families, there are some harrowing secrets that many would prefer to keep hidden. In this case, it is addiction, and the seamless combination of 1950s malaise and morality tale make for a truly unforgettable glimpse into American life, curated by perhaps the most notable of its critics, a director who both celebrated and deconstructed the very notion of the American Dream, and how it wasn’t always as joyful experienced as many who aspired towards it would believe.

Addiction is a recurring social problem in the movies. The frequent exploration of the functional alcoholic, the doomed addict, the casual abuser who slides a slippery slope, and the struggling soul in recovery are tropes of the genre. Beginning in 1945 Billy Wilder made the landmark drama The Lost Weekend. The unconventional flick frightened audiences with its unflinching depiction of alcoholism. Ray Milland, a lightweight B picture actor, picked up an Oscar for his intense portrayal of writer Don Birnam overwhelmed by his addiction.

Since then each year we see Oscar bait productions that seek to show actors at the top of their game as people in dire circumstances. Because addiction remains a lasting and insidious social issue, audiences are drawn to these stories in an effort understand the problem.

We like actors who bring insight into the lives of actual artists who abuse substances to address their insecurities. Arguably some of the best of these performances include Susan Hayward as Broadway star Lillian Roth in I’ll Cry Tomorrow, Diana Ross as the great Billie Holliday in Lady Sings the Blues, and Renee Zellweger as icon Judy Garland in Judy.

Some are functional alcoholics who provide us an honest appraisal of the iron clad grip of addiction. Arguably some of the best of these performances include Anne Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate, Elizabeth Taylor as Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Lee Remick in The Days of Wine and Roses.

Some are nonfunctional addicts whose lives have hit bottom. Arguably some of the best of these performances include Meryl Streep as Helen Archer in Ironweed, Ellen Burstyn as Sara Goldfarb in Requiem for a Dream, Katharine Hepburn as Mary Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Bigger Than Life embraces the distinctive visual of Douglas Sirk who sought elegantly dressed characters living relatively staid lives. The immaculate home, the pristine wife who washes dishes in a designer gown, oversized earrings and full manicure without gloves is unrealistic. The violent flashes Ed Avery endures appear purposefully overwrought. I understand the French critics in later years provided much praise to this disappointment from the 1950s. This stylistic and polite exploration of addiction doesn’t measure up to the work of the films/actresses mentioned.