Something that is very important when talking about queer cinema is that it doesn’t always need to be serious – in fact, most of the greatest films on the subject of the LGBTQIA+ community have been the most charming, effervescent comedies ever produced. When it came to making But I’m a Cheerleader, director Jamie Babbit and screenwriter Brian Wayne Peterson had a small challenge ahead of them – they were intent on telling a story about a young woman’s journey to realizing her sexuality through a tenderhearted romance, but in the form of a peculiar and vaguely absurdist comedy about conversion therapy, a subject that is still quite rightly controversial. Done as the most deranged satire imaginable (borrowing heavily from many sources, most notably one of the pioneers of queer cinema, the incredible John Waters, whose work lingers as a spectre throughout this film), but not neglecting the heart and soul necessary to bring such a story to life, But I’m a Cheerleader is an impressive achievement, a film that is far more complex than we’d imagine based on a cursory glance. It has so much more depth than we could ever expect, and while there isn’t any shortage of laughter to be found peppered liberally throughout this film, it’s the raw, brutal emotional content that keeps us engaged, with Babbit’s skills behind the camera being so effective, it’s staggering to imagine that this was her directorial debut. As a whole, But I’m a Cheerleader is a deservedly iconic cult classic of queer cinema, and a film that traverses some incredibly difficult subjects with poise, respect and a healthy dosage of surreal humour that makes every eccentricity embedded in the film perfectly understandable, and perhaps even supplements the strange but captivating tone that defines the film and has made it such a cherished classic.

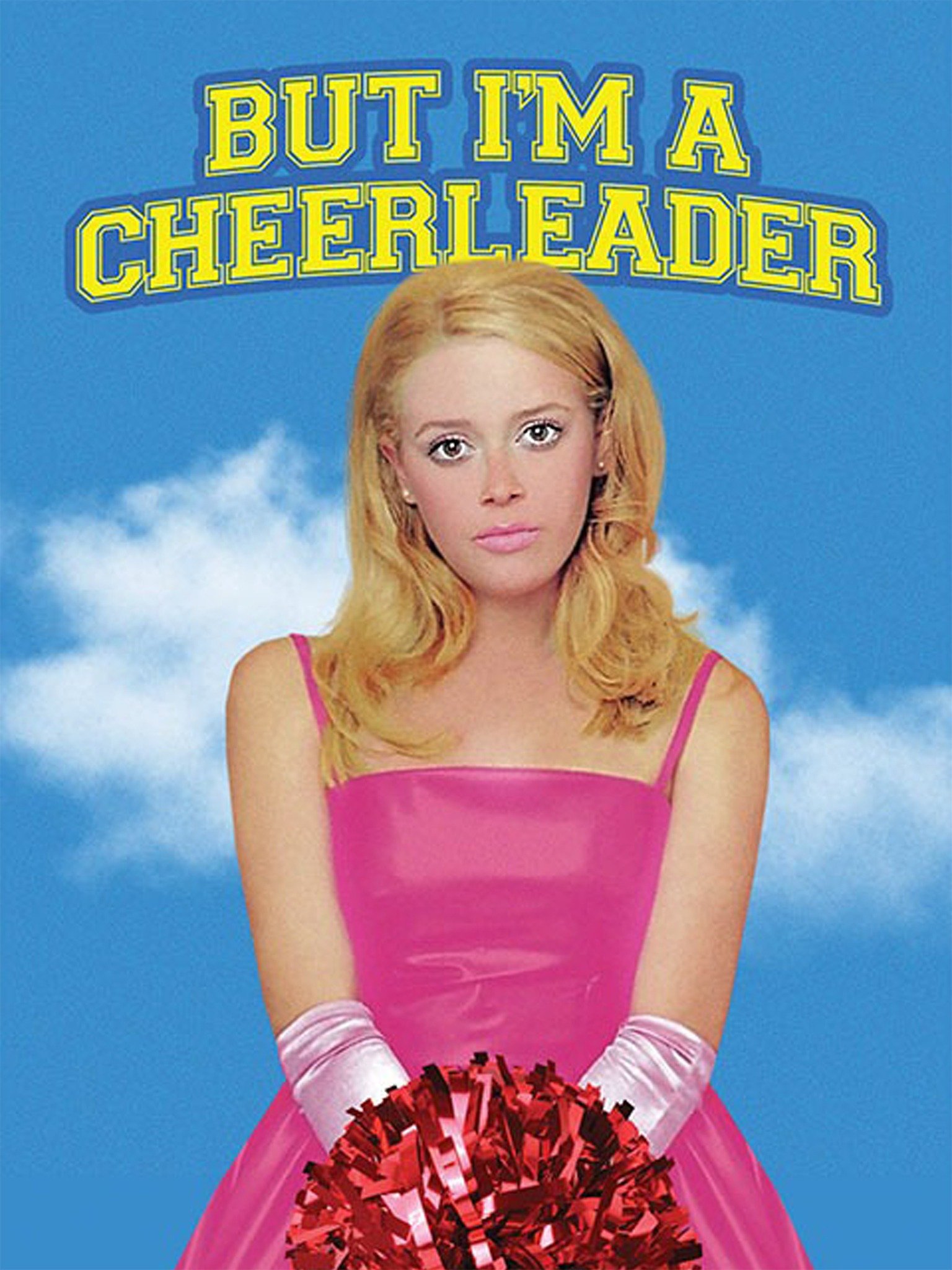

The film focuses on Megan (Natasha Lyonne), who is the embodiment of a regular, All-American high school student – she is mildly popular at school, where she is one of the star cheerleaders, has a boyfriend who is on the football team, and goes home everyday to what she calls her “Christmas-card family” (Mink Stole and Bud Cort), who layer their only daughter with an abundance of love. However, beneath this exterior lies a series of quirks that have become a cause for concern in the life of Megan’s parents, friends and peers, since she is exhibiting behaviour mostly associated with a group they will do anything to prevent Megan from joining: lesbians. They enlist the help of Mike (RuPaul), a self-proclaimed “ex-gay”, who has apparently seen success in converting from his previously deviant desires into the embodiment of the everyday American male. Somehow, Megan’s parents manage to get her to reluctantly agree to join Mike at the most demented summer camp in the country, True Directions. It is here that Mary Brown (Cathy Moriarty) conducts a five-step course in converting wayward teenagers “from homosexuality to normality”. It is here that Megan encounters a range of fellow teenagers who have been forced to go under the care of this deranged woman, who genuinely believes wanting to live a gay lifestyle isn’t only a choice, but the result of decades of propaganda perversions, which she hopes to erase, placing these young people in the position of embodying the spirit of the Norman Rockwell nuclear family, which she considers the ideal image of success. However, it turns out that her program is far from fool-proof, since she doesn’t realize that you can’t easily change someone’s hearts and minds when they are already so intently convinced in living their authentic lives, regardless of the cost with which it comes.

Based on the premise, we already can tell But I’m a Cheerleader is a film that refuses to mince its words. One of the great benefits of a film like this being the feature-length debut for a young director is that there isn’t any reason to play it safe – without a particular reputation to uphold, they stand to gain much more than they will lose if their work is a failure, so it stands to reason many debuts have a sense of renegade originality to them. Babbit’s work here is remarkably raw in how it demonstrates a newcomer staking her claim at a legitimate career by crafting an unforgettable story about intersecting identities and fiery romantic passion, all through the guise of a very strange dark comedy that doesn’t hesitate to both grab the low-hanging fruit and shoot for the stars, often in tandem. Whatever the impetus for this film may have been (which is quite well-documented, particularly in how both the director and screenwriter used their own experiences and knowledge of recovery programs and perceptions around queer identity, to put this film together), the result is a masterful demonstration of using pitch-black humour for the sake of telling a compelling story. It deconstructs many issues relating to the queer community, and while it may not be particularly serious in both form or content, it at least incites a conversation and sets the groundwork for some ideas that haven’t necessarily been absent from the discourse, but not often layered with the interesting approach that a subversive dark comedy often brings to the discussion. Beneath the offbeat sense of humour is the crucial quality that all queer films should aspire to having – a sense of genuine interest in not only portraying real issues relating to the community, but also the sense of communicating the fact that identity is far more complex than we often make it out to be, with every moment in But I’m a Cheerleader feeling more endearing than the last in how it looks at the idea of a queer coming-of-age comedy.

This film is almost worth seeing solely for the performance given by Natasha Lyonne, who has constantly proven herself to be a singular talent. Not a performer known for playing by the rules, Lyonne has enjoyed over two decades of success as something of an indie darling, taking unconventional roles in otherwise straightforward projects that benefit massively from her eccentric personality, while gradually developing her own unique brand of humour that has converged in more significant roles being built around her star persona. The main character in But I’m a Cheerleader is slightly different from the kind of self-assured, cocksure urbane woman she tends to play – but the spark of brilliance she has exemplified for her entire career is present in every frame, with Megan becoming a unique creation, all through Lyonne’s fascinating commitment to a role that could’ve easily have just been a passive character that existed solely to react to the peculiarities that surround her. Lyonne is joined by a galaxy of familiar faces, with some very gifted young actors accompanying her in the central roles, such as Clea DuVall and Melanie Lynskey, both of which would become notable performers in their own right in the coming decades, as well as veterans such as Bud Cort and Mink Stole (who further demonstrates how indebted this film is to the work of John Waters), and a scene-stealing performance from the tremendous Cathy Moriarty, playing one of the more underrated villains of the decade, chewing scenery with a ferocity that that we barely glimpse from actresses of her stature. But I’m a Cheerleader boasts a terrific cast that plays a fundamental role in not only bringing out the inherent comedy, but also humanizing these eccentric characters, who could’ve immediately slipped into parody without the restraint shown by both the director and the cast.

But I’m a Cheerleader may not always hit all the intended targets (and may be somewhat jagged at some points, often feeling as if it put too much emphasis into the concept, rather than following through in the execution), but it earns every bit of kudos for the laborious amount of effort that went into its creation, each moment reflecting the work of a director who clearly knew the story she wanted to tell, and managed to do her best to extract some really complex commentary from a seemingly simple story of burgeoning sexuality and queer identity. Telling a story like this, even through the lens of a very dark comedy, isn’t particularly easy, and Babbit certainly puts in the work to make it endearing. There’s a very narrow boundary between a film like this being a very entertaining comedy, and being outright exploitative and even offensive – the difference being all in the execution, with every subversive joke being complemented by a moment of genuine compassion to counteracts it, making for a perfectly balanced blend of comedy and pathos, which is a rare occurrence for a film like this. Its ability to explore some deeper themes without becoming heavy-handed is one of the film’s most unexpectedly brilliant qualities, and a major reason why this is such a surprisingly deep film – it takes a lot of work to make something that is simultaneously excessively silly but also incredibly profound, and Babbit clearly was willing to put in the effort to bring these ideas to life in vivid detail. Based on a surface-level analysis, you’d be led to believe that But I’m a Cheerleader is just a silly, quaint dark comedy about conversion therapy – but it develops such a genuine heartfulness, and its story is one that speaks very strongly to the intimate issues that are still faced regularly by the queer community.

Films centring on LGBTQIA+ matters continue to change perceptions, and the fact that many of them manage to be entertaining at the same time is only an additional benefit, since audiences tend to react most strongly to content that captivates us. But I’m a Cheerleader is a fascinating experiment, since it takes the form of an irreverent comedy, but gradually unveils a sense of genuine compassion, which is reflected in how deeply this film embraces the idea of queerness as being a continuous journey for many individuals. On the surface, this is a colourful and very bombastic film, filled with visual splendour and an endless amount of visual gags and peculiar jokes. However, if we look deeper, we find something much more meaningful, a kind of enduring honesty that clearly indicates this film was coming from a place of experience for those involved in its creation. This is the kind of film that earns our respect through its unflinching commitment to being itself, and while it may not be perfect, it embraces that fact that it is somewhat rough around the edges, and demonstrates its fervent belief that society should not be shunning those that don’t fit into outdated models of what an ideal individual looks like, and that rather than adhering to the strict confines of the status quo, we should instead be celebrating those who dare to be different. Progress only comes from changing hearts and minds, and while it may not be a definitive text on queer issues, But I’m a Cheerleader does kickstart some very meaningful conversations, which is just as important as directly addressing the problems facing the community. Each work of queer storytelling has a purpose, and in this instance, giving the viewer a good time while quietly inserting some profoundly moving commentary, was the intention, and it succeeded wholeheartedly.