I’d love to say that Zola, the film adapted from a 148-post Twitter thread from 2015, is a work of immense genius and resourcefulness, rather than resigning to the fact that this is an enormous headache of a film. Much of what has been written about this film, which was apparently meticulously crafted from the origin internet thread by Aziah “Zola” King, whose real-time documenting of her odyssey through a low-level Floridian prostitution ring went viral when it first appeared (and deservedly so, it was an online event that kept many of us engaged), and the Rolling Stone article that revisited some of the major players, has been about how incredibly unique this film is. Unfortunately, everything that would make for a good piece of filmmaking is entirely lost, and the result is something that is far more of an annoyance than an entertaining, biographical comedy. The director of the film, Janicza Bravo, has received a lot of acclaim for her work here, with many considering this her breakthrough (while seemingly not realizing that she already made a bona fide masterpiece a few years ago in the nihilistic comedy Lemon, a much better film, as well as a few years of solid directing for a range of television shows) – and while it’s difficult to argue against someone as gifted as Bravo receiving acclaim after years of reliable work, it should’ve been for something much better. It’s difficult to imagine how this film could’ve been improved, and perhaps the best way to have told this story was simply to have left it alone. Unfortunately, as is common with the film industry, anything mildly popular has to be subjected to a lavish production, with the results being disappointing, to say the least.

There are two problems with Zola that should be contradictory – it somehow manages to be both annoyingly frantic, and mind-numbingly boring, which would be the last descriptor one would imagine a film based on something as truly chaotic as Zola’s journey through Florida would be. The first act of the film is promising, since Bravo teases some enticing twists and turns that would normally keep us engaged. However, this is a classic case of a film overselling itself, since it never reaches the apex it thinks it is reaching. Understandably, there is only a finite amount of artistic licence afforded to a film like this, especially since Bravo and screenwriter Jeremy O. Harris make it very clear that they’re trying to keep this as close to reality as possible (rather than deviating from the truth in order to make it more exciting). Selling this as the embodiment of the “reality is stranger than fiction” adage is certainly one way of approaching it, and it would’ve worked had there actually been effort put into developing it into something that feels genuine, rather than 85-minutes of hurried tension, which ultimately builds to a disappointing crescendo, when an entire act’s worth of events transpire in about three minutes. The film promises to be a wild tale of intrigue, filled with sleazy characters that engage in all kinds of sexual debauchery and violence over the course of only a few nights – and while some would think that this would be perfect material for a hilarious and irreverent dark comedy, it just never reaches the point it genuinely seems to be aiming for, leading to a film that frequently deflates itself long before reaching the impossible heights that were maybe always out of its reach.

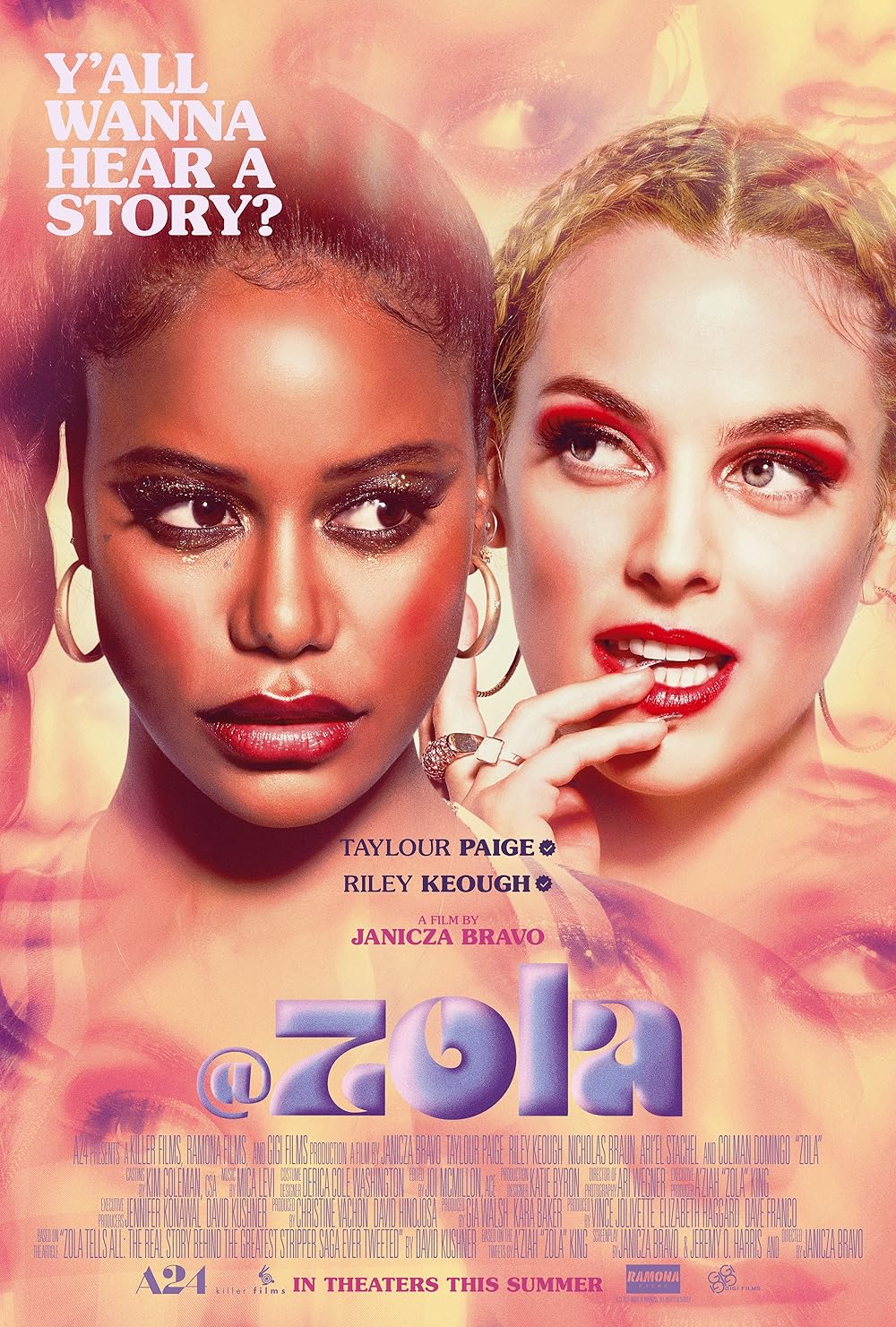

A film like Zola may falter when it comes to executing the story, but there’s always the potential that it could be saved by the performances. Unfortunately, almost entirely across the board, this film is filled with characters that range from barely human to absolutely atrocious, with very few redeeming qualities to be found anywhere. To its credit, it’s clear that Bravo was trying to create an environment where this story was populated by larger-than-life characters, as a way of heightening the stakes and expressing the absurdity of the real-life events that took place. However, the result was an array of unintentionally bad performances that don’t come close to achieving anything particularly noteworthy, despite the talent involved. Taylour Paige plays the titular character, serving as the primary perspective of the film – and while she is a very gifted young actress, she just feels out of place in this film, not quite knowing if she should be playing it entirely straight, or if she is supposed to surrender to the surrealism that surrounds her. Someone who did make a conscious decision in this case was Riley Keough, who turns in an unequivocally bad performance as the catalyst for the chaos of the film, a young stripper who sets off the events, and stands back as the pandemonium occurs around her. Unlike Paige, who is putting in some effort to come across as human, Keough’s performance is a series of poor choices, each one making her character more unlikeable. The rest of the cast isn’t any better – Colman Domingo (a wonderful character actor) struggles to find his voice as the film’s main villain, and Nicholas Braun is constantly ill-served with a character who exists merely as a patsy for the main protagonists, a foil to their madcap performances that really doesn’t do anything. Had the film been more focused on humanizing these characters, rather than giving decently gifted actors these eccentric individuals to portray, it’s possible Zola would’ve improved considerably.

Confusion is the driving factor behind Zola, and while there have been times that films have effectively used the sensation of reckless disorientation, Bravo just struggles to find a particular tone. The film doesn’t know what it wants to be, and instead gradually just disintegrates under the weight of its own ambitions, which were tenuous to begin with. Tonally, there’s a complete lack of coherency – caught somewhere between a gritty, real-life biographical drama, and a sardonic dark comedy, the film struggles to find its footing, and by the time we realize where it is heading, we’ve already become lost to the madness ingrained in the film. Discomfort is a powerful tool when it comes to art, but only in instances when it is used right – Bravo, as gifted as she may be, feels out of ideas midway through the film, with the bulk of the intriguing material being understandably early on, with the back half just being one tense situation after another. It makes the viewer profoundly uncomfortable, but in a way that isn’t effective, and rather serves to just repulse us even more. It feels as if the filmmakers are trying to make a statement, but rather than actually bolstering what could’ve been a promising dark comedy, they instead choose an approach that feels limp and unexciting, while constantly provoking us to feel something towards these characters, without actually putting in any of the work. It’s vague and unlikable, and even when there’s some depth to the feminist message of the film, it sharply turns to the left and presents us with yet another discomfiting situation that feels inauthentic, despite the film’s very ardent belief in its own genuine nature. Not every biographical film needs to stay so close to reality – there is some degree of artistic freedom afforded to filmmakers, and while Bravo doesn’t neglect to use it, it comes through in the most inopportune places, being gaudy when a more simple approach would’ve been better, and vice versa.

If there is a lesson to be found in Zola, at least in terms of the actual fictionalization of this true-life saga, it’s that not every piece of viral media deserves to be made into a film. This is a clear example of a film taking a risk, and it not paying off particularly well. The story of @zolarmoon and her nightmarish road trip to Florida is fascinating enough on its own, and should’ve absolutely have remained on the internet, where it belonged, especially since much of what made it such an entertaining (and tense) piece of media is the authenticity of it. An overly-stylised dark comedy with excessive performances doesn’t service the story nearly as much as it thinks it does, and it even comes close to removing the unique lustre of the thread that inspired it, since it turns a truly awe-inspiring piece of chaos into a mainstream production, which is counterintuitive to what film normally is supposed to be. Whether or not this was the purpose, Zola is a genuinely unpleasant film, and it’s not nearly as fun as it thinks it is. Designed as some dizzying, entertaining thriller with broad overtures of dark comedy, but without any of the charm needed to elevate the material beyond a mere novelty, the film just falls apart before it reaches even a slightly coherent point. This could’ve been so much more powerful, since there is a kind of bravery that comes with telling a story about sexual liberty and feminist issues – it just loses a lot of its power when it’s layered under vaguely pretentious techniques and a kind of malevolent approach to developing characters that pushes us away far faster than it draws us in, which becomes something of a problem when the film surrounding a promising story refuses to move beyond a certain point. Zola doesn’t do much justice to the subject matter, and rather than making something that was already thrilling into a wonderful cinematic odyssey, it just comes across as gauche and unlikable, which is only doing a disservice to a truly interesting piece of internet culture.