In 1983, Bill Forsyth quietly made history when he wrote and directed Local Hero, his quaint and charming comedy about an outsider being stranded on a remote Scottish island, and forced to cavort with the eccentric local residents who may not have had ill-intentions, but certainly didn’t always mean as well as they seemed to think they did. What made this film particularly resonant is how it presented audience with the concept of an outsider undergoing a journey to try and find himself, separated from nearly all of his creature comforts, and instead having to find salvation within the most arid community he could possibly imagine. Ben Sharrock seems to be taking a cue from Local Hero in the form of Limbo, which could be considered something of a spiritual successor to Forsyth’s film, particularly in how it carefully and gracefully moves between endearing comedy-of-manners and heartbreaking, character-driven drama – and also adds in layers of hard-hitting social commentary that makes it a truly unforgettable experience, a film that can be challenging to watch considering the subject matter it is based around, while never abandoning the hope that inspired its existence. Sharrock is an immense new talent, and working with a cast of mostly unknown actors plucked from all around the globe, and placed on this strange but charming island somewhere far from reality, Limbo is an extraordinary triumph of humanity that gives us strong evidence to the power of the smallest films to leave the biggest impressions, and where even the most disconcerting adventures into the heart of the past can be seen as positive when the intentions are pure and the execution is well-devised.

Limbo is a film about outsiders – whatever way the viewer wants to look at it, Sharrock essentially made a film composed of only people who don’t belong. Whether it be the main characters, a rag-tag group of asylum-seekers forced to take up residence in a small Scottish village, or the motley crew of supporting characters who serve as the inhabitants of this fictional location, everyone in this film seems like they don’t seem to exist in communion with anyone else. This is at first an excuse to make this as irreverent and off-the-wall as possible – who of us aren’t sometimes endeared by a well-measured dosage of peculiar, quirky humour? The use of stark, deadpan humour and heightened personality types does initially mislead us into thinking Limbo is going to be a lot more blase about the issues at its centre than perhaps we feel comfortable admitting – but the director gradually strips away the layers of humour and reveals a very tender, heartwrenching story about loss in various forms, and how one young man makes his way through a completely foreign territory – both in terms of his environment and the people who occupy it – literally carrying his past with him, fearful of losing everything he cherishes so dearly. Sharrock is taking some very bold risks with this film – Limbo could’ve easily have used strange humour to outweigh the serious conversations, rather than complement it, which was eventually the method he took. Finding the right balance between levity and gravitas takes a very skilled filmmaker, and for someone so young and relatively inexperienced as a director, Sharrock demonstrates a very keen and forthright vision that makes him someone to keep a close eye on, since his manner of taking what is essentially just a story of a young man wandering through pastoral Scotland, and turning it into a series of meaningful conversations, is astonishing.

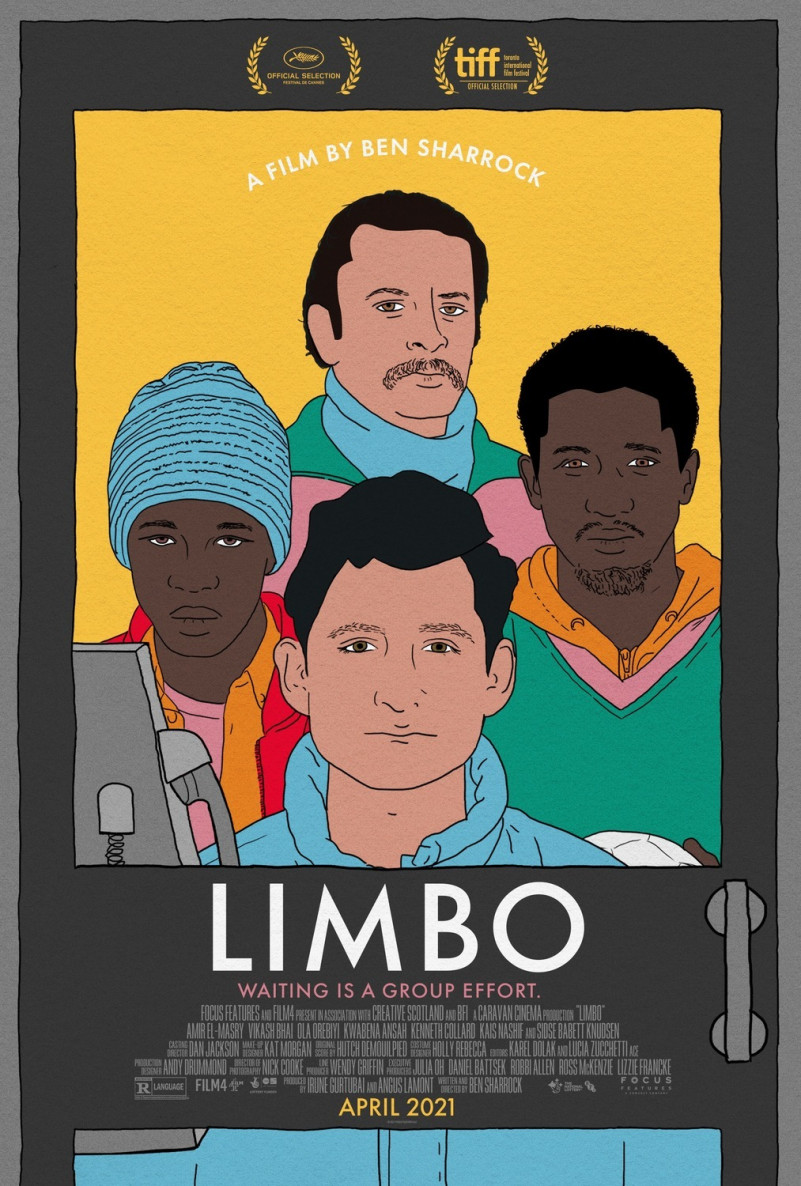

The director is massively helped along by his ensemble, which consists of some tremendously gifted actors. Some of them are newer to many of us, others familiar faces that take us by surprise when they appear on screen. The film is led by Amir El-Masry, who plays the quiet and introspective Omar, a Syrian immigrant who is desperately trying to find his way off this island and back into the functional world. He doesn’t have much interest in countryside living, and instead wants to pursue a career that not only allows him to express his passion for music, but provide for his family, who have receded into being voices on the other end of a telephone conversation, rather than the people who surround him. The young actor is absolutely marvellous – he doesn’t speak a great deal, and most of his performance is contained in his physical movements and expressions (the film emphasizes body language as a legitimate means of communication – we may not all speak the same language when it comes to the verbal channel, but a smile or frown means the same to everyone, whether you’re a refugee from the war-torn Middle East, or a pernickety Scottish fisherman returning home from a day at sea), and he develops into a truly compelling protagonist. Vikash Bhai is a scene-stealer as the charming Farhad, who has a much more positive outlook on life, and whose optimism turns out to be far from delusional, as he seems to be the only person who seems to have a way out of this island. Smaller performances by Ola Orebiyi and Kwabena Ansah (as bickering African immigrants struggling to accept that they can’t achieve their ambitions), Sidse Babett Knudsen and Kais Nashef all round out this cast and make it such a beautiful poignant ensemble that manages to find the truthfulness in these characters that could’ve so easily been archetypes, void of any personality outside of their peculiar quirks.

If there is something that Limbo sets out to prove, it’s the importance of community. This isn’t a rare subject, especially for films that take place in isolated regions, and focus on outsiders trying to make a home for themselves, in spite of the circumstances. The concept of unexpected friendships springing from bad situations is not one altogether new to fiction, but it’s something that Sharrock beautifully explores in this film. What starts as a peculiar array of lovable eccentrics patiently waiting out the verdict regarding their refugee status on an isolated Scottish island eventually flourishes into one of the most poignant explorations of humanity anyone is likely to encounter – but it does come at the cost of some enormous emotional baggage, with which the director is clearly not against bombarding us. It takes a lot of effort to make something so endearing out of a series of tragic moments, strung together with light touches of comedy that helps carry the story forward, but Sharrock achieves this without any difficulty, carefully deconstructing the lives of these characters – and in the process the entire idea of seeking asylum – all through the lens of a sweet and sentimental drama about community values. The cheerful demeanour of these characters, and the unexpectedly close-knit kinship they have for one another, masks some bleaker reality of these people, who find themselves stranded away from their homes, their past a distant blur, their futures an entirely uncertain destination that they aren’t even sure they’re going to reach. As the title suggests, they’re stuck in limbo, a kind of purgatory where life isn’t particularly difficult, but it could be a lot easier, especially when it comes to establishing a clear direction.

Limbo is a magnificent film, but one that needs to rely on the word-of-mouth of those who love it, because it’s unfortunately the kind of small, independent drama that flies under the radar without the right amount of conversation. There isn’t much to sell this film on other than a few key components – it’s very sweet use of comedy to punctuate some shattering emotional moments (there are numerous sequences in this film where we are completely thrown out of the irreverence and into the dark reality of these individuals), the lovable characters who have a lot more depth than we’d expect at first glance, or the story that touches on a range of issues, from the purely trivial to the overwhelmingly disconcerting. However, if there is only one reason to seek Limbo out and invest in this world created by the gifted young director, it would have to be the compassion – rarely do we find films so deeply and unequivocally profound in how they treat their characters not as pawns in some broadly ambitious artistic endeavour, but as real people reflecting a particular time and place. There’s a heartfulness to this film that is so difficult to avoid, forcing us to fall in love with these people, both the fictional characters as well as those who they represent. There were so many opportunities for cheap cultural humour, or an endless bombardment of irritating stereotypes, but Sharrock manages to consistently take the high road in every instance, delivering a stellar drama about the refugee experience that is more insightful and powerful than nearly any other work of fiction that focuses on this harrowing reality – and through his honesty in telling this story, and his willingness to add some humour to the proceedings to help it along, he creates one of the most stunning films of the past year, and a mercilessly powerful testament to the human condition.