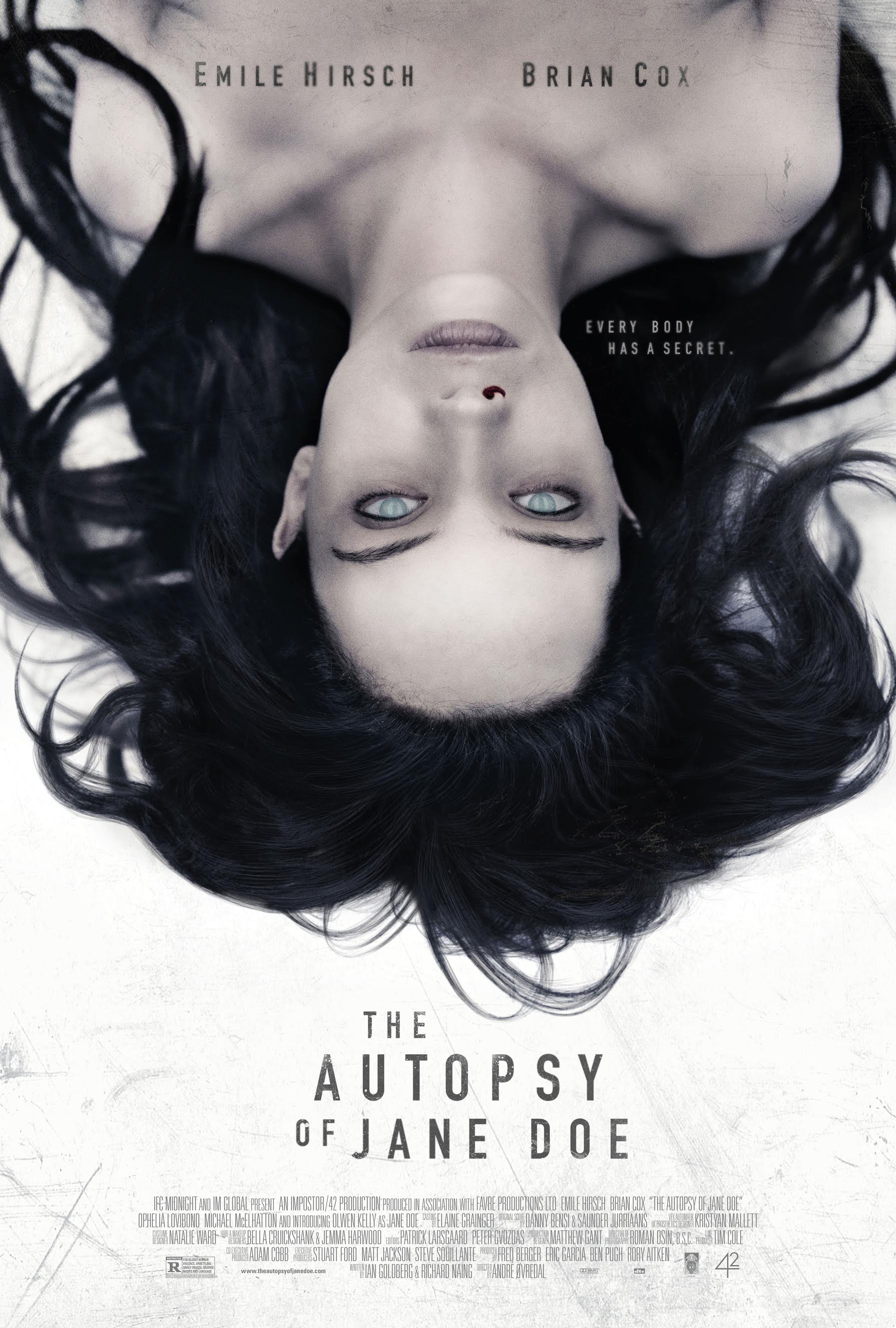

While he may not be credited for inventing or even defining the genre, André Øvredal did contribute significantly to the success of the found-footage horror film when he made Trollhunter, one of the most wildly unique works of terror produced in the last two decades. However, in speaking on the successes of that fascinating piece of folkloric horror, the director made sure to prove that he wasn’t one to rest on his laurels, and was in search of something profoundly different – this turned into The Autopsy of Jane Doe, a film that may not be as startlingly fantastic as his previous work, but instead functions as a return to the most fundamental aspects of the genre. On the surface, the film doesn’t appear to be all that interesting or enticing – two men, a father-and-son duo of coroners, are tasked with examining a mysterious body, which had been brought to them without any identification, for them to provide a cause of death to the authorities so they can close this case. It is common work for the veteran medical examiner and his son, who doesn’t see this as too much of a challenge. It’s just another day at the office for them – until strange events start to occur all around them, and they realize this body harbours some very dark secrets. It seems like a rather conventional film, and in many ways, it does fit within the confines of the genre, following familiar patterns and being predictable, but only to a point. The brilliance comes in how Øvredal uses his own experience as a genre director to pull apart the strands of narrative, uncovering the dark, underlying details that make The Autopsy of Jane Doe such an oddly hypnotic, and undeniably terrifying, excursion into the dark recesses of the human mind and its relationship with the environment around it, and a meaningful commentary on the value of minding one’s own business, since curiosity seems to be capable of killing far more than the cat, as this film makes abundantly clear.

Øvredal makes short work of the horror in The Autopsy of Jane Doe, which could’ve very easily fallen victim to the same ridiculous, overwrought conventions that tend to hinder many subpar horror films. Just because the film didn’t have a massively original starting point doesn’t mean that it is any less impressive, since the brilliance comes in how the director tackles the script by Ian Goldberg and Richard Naing, who designed this film as less of a horror, and more as a psychological drama. Make no mistake, this is an absolutely terrifying film – but what we’re led to believe is the root of the horror turns out to be merely a non-sequitur, with the real terror coming from the most unexpected sources. There’s a degree of dignity to a film that not only respects the audience in giving them the benefit of the doubt (as opposed to overexplaining every detail), but also contributes something to the genre, regardless of what it is specifically, The Autopsy of Jane Doe is a very simple film, but one that knows exactly the direction it wants to go – it is assured, and clearly designed with a specific target. However, the destination is not necessarily the end-point of this film – this isn’t a case of trying to escape from a hostile situation. Instead, this is a carefully curated series of moments, in which each new scene brings something to the story, whether it be a minuscule detail or an enormous progression in the plot. The journey is the main propellant of The Autopsy of Jane Doe, and through placing us in a voyeuristic position of passively observing these two men working, and watching as the world around them becomes to make less sense the more they unravel the mystery, alternates between utterly terrifying, and almost profoundly ingenious. They simply don’t make films like this anymore, where the most simple premise can be fertile ground for a stark, brilliant discussion on both the genre itself, and the ideas contained within it.

The Autopsy of Jane Doe is quite literally a deconstruction of the horror genre, with the format of the film being oddly playful, at least in how Øvredal and the two screenwriters structure the story. The two main characters are delivered a body, and asked to analyse it – so begins an ordinary assignment, which is so common for these coroners, they have a clearly defined, step-by-step process of conducting it. Methodology is a vital component of this film, since it allows the director both the plot guidance that would prevent this film spiralling out of control (often a significant problem for many horror films that are a bit too ambitious for their own good), but also the free-reign to carefully manipulate the story to fit his own intentions. The horror is gradual – the sense of unease is present from the start, but it’s nothing you couldn’t find in your garden-variety horror film. Where this film differs is in how these traditions are altered to fit the growing tension – situated in a single room, from which the characters barely leave, there is a sense of entrapment that governs the film. As far as they (and the audience) are concerned, for the few hours in which they’re conducting this autopsy, there isn’t an outside world. This lack of distraction for the sake of peaceful work turns out to be a hindrance, since the tranquillity of isolation becomes their biggest challenge. Over the course of this evening, strange occurrences abound – and Øvredal is very creative in how he represents the growing terror, measuring it out in healthy doses that keep the film engaging, but obviously prevent it from becoming contrived. After all, this is an unhinged, supernatural horror that is designed as a quiet, independent drama – so while the film delivers exactly what it promises, it doesn’t always come in the form we’d expect.

Rather than allowing everything to descend into madness at once, the director instead calculates each moment with a careful precision that can only come from a firm understanding of what terrifies us as human beings, as well as the skillfulness to employ these very visceral qualities into the film in a way that feels genuine. Part of what makes this film so compelling is that, even when it is dealing with very dark supernatural material, it doesn’t seem all that divorced from reality, since it draws on recognizable conceptions of human fear, rather than simply imagining what could conceivably shock and horrify the viewer. We may avoid the horrors that we can see, but we are most fearful of those that lurk just out of sight, and the heightening suspense employed throughout The Autopsy of Jane Doe is so palpable, we ourselves start to feel as if we’re falling into the kind of hysterical madness that these characters are narrowly avoiding. Despite the madness that persists through the film (and there is an abundance of it), the director never lets the film spiral to the point of no return – everything is kept very simple, and even at its most deranged, The Autopsy of Jane Doe is still very measured and straightforward. This doesn’t only give the film the space to flourish into something very memorable, it prevents it from hiding in any of the recesses that a lesser filmmaker would rely on. Øvredal knows exactly what is going to scare us, and the big revelation (which I won’t reveal here, in order to allow anyone who has not seen this film to experience these demented twists and turns for themselves) comes across as surprising, but still without lacking the nuance it needed to be convincing. This is a very gritty, dark film, but it has serious depth to it, each detail contributing to the growing sense of despair that essentially defines the film and makes it such a peculiar work of horror-fueled artistry.

Going into The Autopsy of Jane Doe, not even the most accustomed viewer can anticipate the scope of what they’re about to see – and perhaps it is better this way, since not only does it leave room for the film to take us by surprise, it helps define this insidious tale of the supernatural interweaving with the deep curiosities of the human condition. This is the kind of terrifying, small-town horror that leaves the viewer profoundly unsettled, and thoroughly disturbed, which is more than many of us bargained for when entering into what appeared to be a relatively run-of-the-mill psychological horror. Helped along massively by some stunning work by Brian Cox and Emile Hirsch (both of whom are at their peak playing these characters), and a script that can occasionally veer towards cliche, but quickly catches itself long before it can be written off as even nearly conventional enough to qualify as anything other than a massively successful piece of horror filmmaking. Unfortunately, The Autopsy of Jane Doe has flown too far under the radar since its release, and the intentional framing of this as more traditional horror fare, while understandable, doesn’t even come close to encapsulating an iota of the madness embedded in this film. It is filled with shocks and surprises, and is oddly captivating, even for a film that is essentially wall-to-wall terror, condensed into a space so small, not only does it play on our inherent apprehension of the unknown, it may even inspire new fears in the viewer, which is perhaps one of the most resounding pieces of praise one can assert on a film. Entertaining, terrifying and incredibly well-made, The Autopsy of Jane Doe is one of the finest horror films of the past decade, and a truly triumphant exemplification of the incredible work that can be done when an audacious filmmaker is given the platform to explore their artistic curiosities.