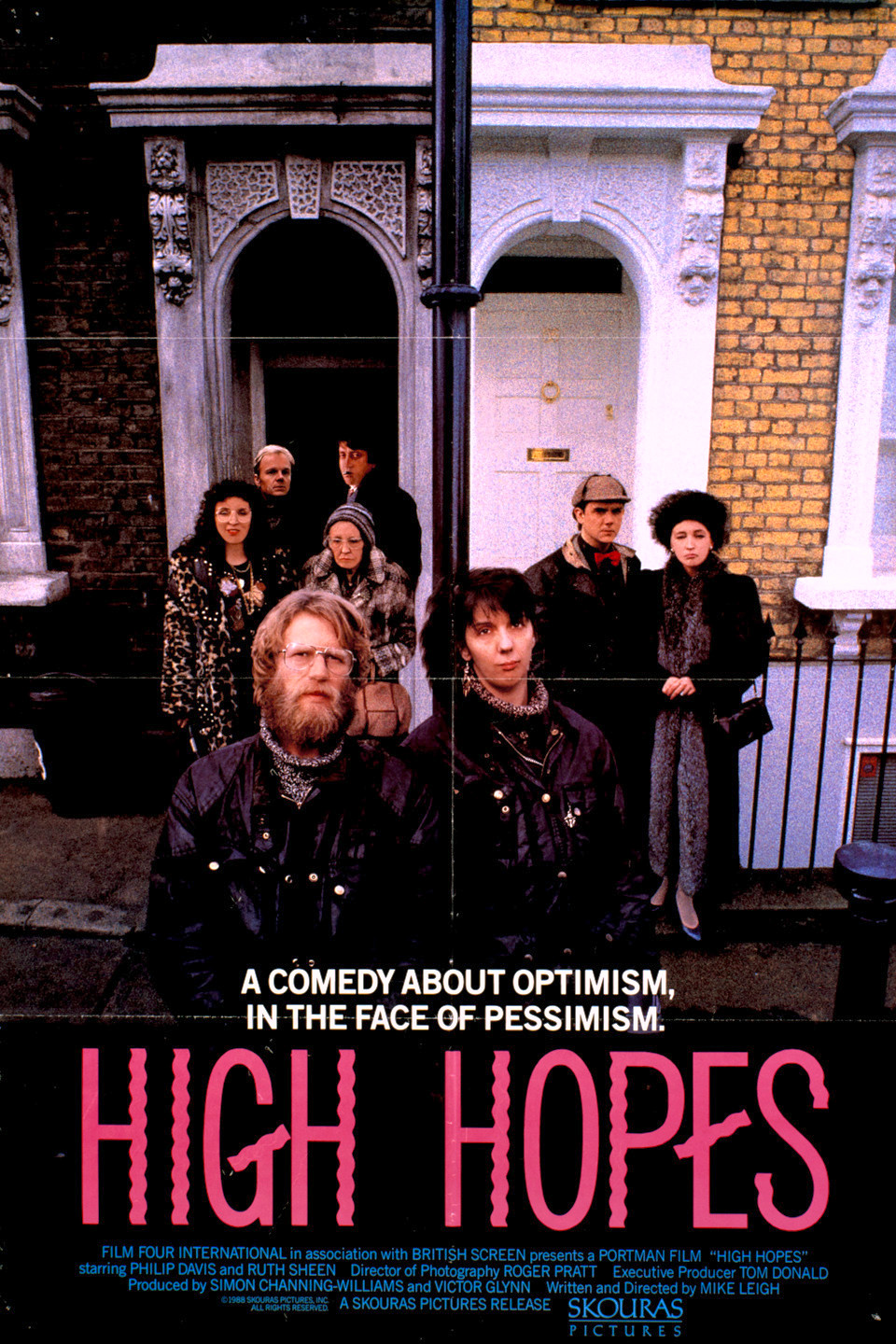

No one tells stories quite like Mike Leigh. He has devoted almost his entire career to bespoke explorations of the working class, taking the viewer into the intimate recesses of a nation torn apart by the broken promises of the Thatcher regime. His earlier films are also the ones that are propelled most notably by his fury towards the socio-political system of the United Kingdom that he had come to know during his artistic career. As one of the defining members of the class of “angry young men” that used a combination of their youth and disdain for conservative values to craft brutal indictments on the political system, Leigh was truly someone willing to put everything on the line in favour of providing only the most scathing commentary that would expose the injustices he saw every day as a socially-charged artist with a keen eye for the smallest existential details that govern daily life. This, coupled with the director’s magnificent ability to use humour to constructively curate a harrowing portrait of modern life, make for several wonderful works that show a different side of England, funnelled through his idiosyncratic perspective. One of his more unheralded films is High Hopes, which isn’t only one of his most moving stories, but also the film that I think best encapsulates everything about what makes Leigh such an iconic filmmaker, someone who gets to the very core of the human condition and creates something powerful from fragments of reality, which has always been one of the director’s most essential qualities, and what has led him to become such a beloved cinematic figure, even if his work is often the kind that unsettles more than it entertains. A wonderfully simple but deeply provocative slice-of-life drama with a jagged satirical edge, High Hopes is one of Leigh’s more compelling works in both form and content, even at its most challenging.

Leigh may have worked in a range of different genres throughout his career, oscillating between different forms of comedy and drama, and even trying his hand at a few historical epics and an occasional psychological thriller while he was at it. However, his best films are always going to be those that feel closest to home for the director, and High Hopes is the embodiment of both his existential curiosities and socio-cultural ravings, channelled into an enduring drama about a family trying to work towards a livable future, and hoping that whatever transpires as a result will help make life slightly more comfortable from them. With the exception of a few of his films, Leigh normally focuses on telling stories of ordinary people, his interests lying within the working-class society he came to be familiar with through his own upbringing in post-war England. It gave him a unique perspective that allowed him to critically comment on all areas of life, without becoming too heavy-handed in his approach, since his intention has always been to merely describe more than persuade, which is a primary reason towards his status as perhaps the most notable filmmaker in the school of kitchen-sink realism. In this regard, perhaps only Ken Loach (who made similarly complex films that sought to represent the realities of Thatcher-era Britain) is able to come close to the scathing but simple portrayals of the inner machinations of a country torn apart by political turmoil, which in turn informs much of their opinions on the rest of the social issues they come into contact with, even those that should not be guided by political ideology. This is a tall order for films that intend to function as simply just simple depictions of the trials and tribulations of the regular British citizen – but even with the peripheral social details, these films are beautifully poetic and incredibly compelling, which is par for the course when it comes to Leigh’s films.

The difference between Leigh’s work and that of some of his contemporaries (and the filmmakers he inspired), is that they’re hard-hitting and focused on eviscerating the social hierarchy, but never veer towards misanthropic. High Hopes exemplifies this, as there is a disconnect between the narrative and the underlying social message. On the surface, this film is a cheerful story about a family going about their day, meeting various people and finding themselves in the midst of various humorous situations – Leigh has never been a stranger to crafting stories along this line of endearing comedies-of-manner, where the misadventures of everyday life are repurposed into wonderfully upbeat stories that endear us to the characters. Yet, beneath the surface there is something more sinister, a sense of despair and disquieting melancholy that gradually increases as the film goes on – we see this in how the characters develop in a relatively short space of time. Each one of them harbours some inner turmoil that they try to avoid revealing to the rest of the world – whether it be the happy-go-lucky couple trying to spread positivity in public, but battling behind closed doors on account of their wildly different interpretations of their shared future, or the young woman who has high-society aspirations but can’t escape her meagre working-class life, or the elderly woman who tries to mind her own business, but is constantly pushed into the lives of other, until she is at the breaking point, without any peace to be had in her final years as a result. Leigh portrays the lives of these characters with such incredible precision, creating stories that can be told through only a few brief utterances, or even just through their faces, whereby Roger Pratt’s camera lingers slightly too long on a single shot, allowing us to see through these facades and understand the complex lives that underpin these characters and make them more than the thin archetypes that they appear to be at the outset.

Leigh’s films are communal experiences, and each of his actors is equally responsible for developing their characters and turning them into the fully-formed individuals that we see on screen. His method of working with his actors in a much more personal setting has established Leigh as someone who can attract incredible talent, all of which tend to fit into his regular ensemble of repertory players, a few of which had their start in High Hopes. It’s not necessary to wax poetic on most of these performances, as Phil Davies and Ruth Sheen give solid performances, and Lesley Manville is as much of a scene-stealer here as she should be in nearly every project she appeared in for the next thirty years – they’re solid and memorable performances that we’d expect from a Leigh film. However, the best performance comes from someone who is on the outskirts of the director’s regular ensemble, appearing in mainly minor roles, but is placed at the centre of this film. Iconic character actress Edna Doré gives one of the finest performances across any Leigh film, playing the lonely elderly widow who only desires to live out her remaining days in quiet solitude, but is often thrust into the lives of her children, who see her as less of a mother, and more of a tool to progress their own individual agendas, using her to their benefit when it is necessary. Doré is just incredible in the part – her eyes tell a dozen stories, and the camera is so utterly enamoured with her, capturing each wayward emotion with an incredible sincerity that can’t be found in many performances. She brings the spirit of the ennui Leigh was trying to evoke through this film better than perhaps anyone else ever has, and delivers the most heartbreaking performance in a film that sets out to shatter us through presenting the audience with the harsh realities of existence.

High Hopes is a fascinating film, and an incredibly powerful achievement hailing from a director who understands the extent of human existence better than most. He tells stories through the lens of working-class strife, but is never plumbing for emotions in a way that feels inappropriate. Everything is so authentic, and he keeps the narrative simple and straightforward, to the point where it feels like we are voyeurs, looking into the lives of a family at a time when tensions around political ideology and social order were at their most palpable. Leigh’s films are breathtaking precisely because they feature such a deft balance of so many different tones and themes, so it’s difficult to pin them down and view them as works solely within one particular set of conventions. Some of the commentary may be incredibly obvious – one just needs to look at one of the early scenes to see this, where one of the main characters and her neighbour return home at the same time, their dialogue overlapping and showing the difference in both deportment and the content of their conversations, which paints a multilayered portrait of Britain during this period. The interweaving lives of half a dozen characters is more than enough space for Leigh to press on and tell a story of individuality set to the backdrop of an oppressive system that benefitted far fewer people than it actively put at an indelible disadvantage, their lives being caught in a cycle of perpetual suffering, where only the most superficial pleasures could dull the pain of existing in a country that seemed to care very little about the people that formed its foundation. All this simmering anger is filtered into this staggering drama that is never overwrought, but instead very creative and insightful about the message it delivers – and if one needs any proof that Leigh is a genius, you can easily just look towards High Hope, which exemplifies that even when playing in a slightly minor key, he still makes something captivating, moving and thought-provoking, yet another instance of his incredible talents as one of the most important filmmakers of his generation.