If there was ever a lesson to be learned from crime films made during the Golden Age of Hollywood, it was that crime doesn’t pay. It was incredibly rare to find a film focused on a criminal that ends with them getting away with the crime, or at least not facing some consequences as a result of their misdeeds. This was mostly a result of the Hays Code, which forced productions to ensure that, should a major character be someone on the wrong side of the law, that he or she find themselves on the right side of it before the credits rolled. This led to a degree of predictability with lesser works, but also served as a fertile opportunity for directors like Michael Curtiz to add layers of additional commentary onto the proceedings. Angels with Dirty Faces is a film beyond iconic, serving as arguably one of the finest crime films ever made. The story of two childhood best friends heading down completely different paths as they got older, one becoming a hardened criminal, the other a dedicated priest, was a perfect opportunity for Curtiz to combine different genres, merging a character-driven drama with a crime thriller in a way that might be somewhat predictable, but makes exceptional use of the conventions it’s built on, to the point where the experience of seeing what the director does with this material is almost as impressive as some of his later efforts, many of which he is most known for. This may not be his commercial or critical peak, but Angels with Dirty Faces is still an astonishing film, and one that has absolutely earned every bit of its legendary status as one of the finest films of its era.

It’s certainly easy to dismiss Angels with Dirty Faces as yet another 1930s gangster film based on a quick glance, because the premise itself doesn’t lend much credence to the idea that this film is doing anything differently, nor does the original novel by Rowland Brown, which is often considered another notable but unremarkable entry into a long canon of pulp fiction stories). However, one shouldn’t be hasty when judging this film, since what appears to be a relatively conventional film is actually simmering with complexity. Curtiz may not have been the most proficient storyteller, nor the most gifted visual stylist (but mercifully, these components were placed in the capable hands of screenwriter John Wexley Warren Duff and director of photography Sol Polito), with the director’s responsibility being to guide this story from the page to the screen, creating something vivid and memorable, without deviating too far from the pattern that has been tried and tested for years. It’s important to not overlook the fact that Angels with Dirty Faces is not built on a foundation of a simple crime thriller, but instead a character-driven drama about bad choices and broken friendships, which makes the classification of this film as a gangster film tenuous, with those aspects being supplementary to the plot, rather than the device that propels it. For viewers who aren’t interested in early noir and gangster films, this one provides a welcome change of pace, while devotees of the genre will doubtlessly be captivated by the unique approach taken to telling such stories – there’s very little accomplished in this film that isn’t impressive, which is perhaps the main reason it has succeeded in standing the test of time for over eight decades, continuing to find supporters to the present day.

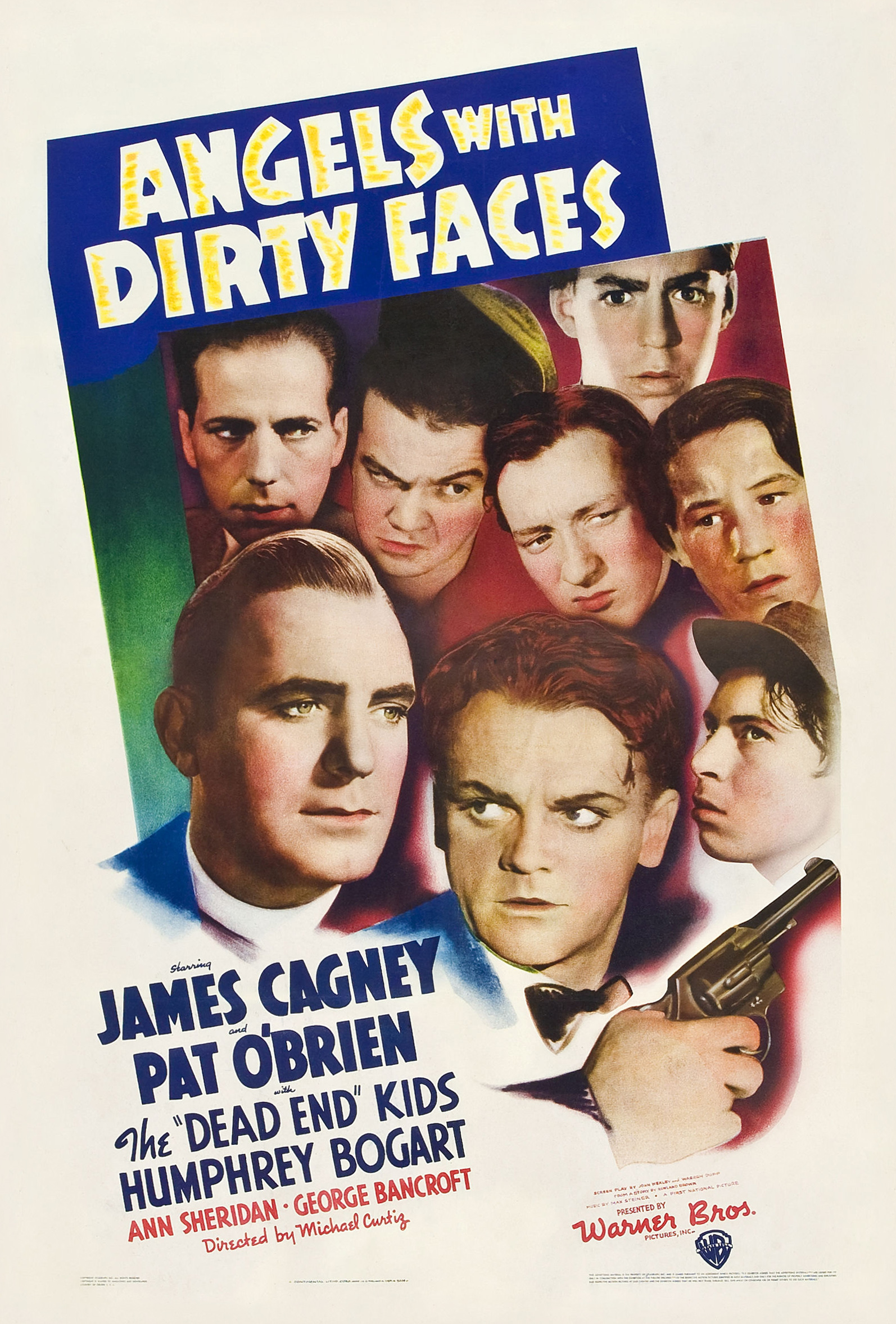

If anything, Angels with Dirty Faces is mostly remembered as a starring vehicle for James Cagney, who had been working reliably to the point of being a household name, and was one of the dominant talents in Hollywood at the time. This film presented him some more challenges than usual, forcing the actor to expand his skills beyond simply playing quick-witted, maniacal gangsters – he not only needed to assimilate these qualities into his repertoire, but also taken on a new set of characteristics in constructing the character of William “Rocky” Sullivan, who is far more than just a one-dimensional criminal, but a man wronged by both his own actions and those of the institution. Cagney is obviously tremendous, and the film realizes his talents very early on, enough to not only showcase his remarkable ability to do absolutely anything with a role, but also to step aside and allow some of his co-stars the space to showcase their own talents. Pat O’Brien is the emotional heart of the film, playing the principled priest who does everything he can to help his friend, while knowing that his duty isn’t to a childhood chum, but rather to society in general, which causes the rift between the two men to form. Humphrey Bogart is also unforgettable in a smaller role as the film’s primary villain, a crooked and malicious lawyer that sharply reflects the more heroic characters he would play at the height of his fame (Bogart would play a similar role in another terrific Cagney vehicle the following year, The Roaring Twenties, highly recommended for those who are fond of this film). The film is propelled by the deep and genuine fondness it has for its characters, and it showcases some incredible empathy that makes it quite an extraordinary piece of filmmaking.

From the first moment, we know Angels with Dirty Faces isn’t going to be a typical gangster film, with the emphasis clearly being on friendship. Allegiance to the past is a pivotal theme to the film, and whether it be reflected in Rocky’s tumultuous friendship with his former childhood companion after both have chosen radically different paths in life, or the insidious partnership between the main character and his supposedly loyal business partner, who actually betrays him the first moment he can. This is the aspect that the film is most interested in considering, focusing on the complex human dynamic that exists between several different characters – it allows for some remarkable performances, but also gives the film an unexpected amount of depth, an increasingly rare quality that the film succeeds in utilizing very well, taking this beyond a run-of-the-mill crime thriller and instead focusing on the individual moments that are often left out of more mainstream versions of such stories. Curtiz and his collaborators approach this story with a deep sense of empathy – they’re not too focused on the more crime-driven aspect of the plot (even if it is very important, and therefore doesn’t go entirely ignored), and instead venture deep into the more serious material, layering on some incredibly complex meta-commentary about society that is truly disconcerting, especially considering how the concept of corruption and the flaws within the criminal justice system are not any better today than they were in 1938, which gives Angels with Dirty Faces an unexpected amount of resonance that elevates it far beyond a novelty of a bygone era. These small details, when put in contrast with the broad narrative strokes, make for a truly captivating example of poignant social critique being merged with mainstream filmmaking.

Angels with Dirty Faces is a masterful, humane drama constructed in the form of a captivating crime thriller, brimming with a unique energy that keeps us engaged and enthralled for the entire running time – and it’s certainly not a mystery as to why it has remained a classic of the genre for so many years, still readily embraced by audiences across every conceivable demographic. It speaks to deeper issues in the worldwide culture, which are reflected in the small, intimate and human moments that occur between characters, each one of them having made decisions to follow a particular path, and now have to stand by their choice, since it’s almost impossible to change the course of one’s life once you’ve chosen a particular journey. Anchored by one of the greatest performances Cagney ever gave, and told with wit, precision and a candour that is far more powerful considering the genuine roots of the story, Angels with Dirty Faces is an incredible achievement, a film that works just as well on the first watch as it does when a viewer revisits it. Complex and layered, but still incredibly accessible and perfect calibrated in terms of both narrative structure and emotional content (leading to several sequences where it tugs on the heartstrings), the film is an absolute triumph, and certainly one of the very best of its kind ever to be produced by a major studio, and one that has aged better than many of the pale imitations that sprung up as a result. It’s an unexpectedly moving film, and an absolutely essential part of the history of the Golden Age of Hollywood, which relied on such original productions to prove how it could honestly move even the most cynical of viewers, while captivating those who are fully invested in the strange version of the world it presents to us.