Breaking from tradition was not always Alfred Hitchcock’s speciality, particularly in the subversive little quirks that defined his films. Regardless of how strange and bewildering his stories were, all of his films were distinctly his own. This required director himself to appear before the start of The Wrong Man, speaking directly to the audience as he remarks that, unlike many of his films, the one we are about to see is profoundly different, insofar as it is based on a true story, with the facts of the real-life events guiding the progression of the entire film. Hitchcock was someone who understood the artistic licence that he was offered as a director, and never failed to employ it, crafting unforgettable mood pieces with more suspense and intrigue than perhaps any other filmmaker we’ve seen so far. However, The Wrong Man is still one of the filmmaker’s finest works, if only for the sake of being a radical departure from some of the more notable directorial flourishes, and it shows the range that Hitchcock possessed, even when working within a genre he not only knew very well, but essentially helped design, to the point where he is definitive of this kind of filmmaking, his name synonymous with intricate, plot-driven psychological thrillers with healthy doses of dark, maniacal suspense. He made something quite special with The Wrong Man, a quiet but still thoroughly engaging thriller that takes us on a journey, this one in particular more terrifying than usual, since it is all rooted in reality, a fact that the director and his cohorts never fail to keep reminding us, since it only contributes to the general looming atmosphere lurking throughout the film, ready to pounce without a moment’s notice.

The Wrong Man is perhaps Hitchcock’s most minimalistic work, in both form and function. The story of an ordinary jazz musician and family man who is arrested under suspicion of being a notorious local criminal known for robbing a variety of establishments, is one that is certainly ripe for Hitchcock’s distinctive brand of suspense. However, at its core, this film is still quite different from anything we’ve seen the director do before, to the point where we forget that we’re actually watching a Hitchcock film, since so much of what underpins this film seems like the antithesis of the lavish, labyrinthine psychological thriller, where we are invited to luxuriate in the existential despair, which becomes oddly entertaining as more of the story unfolds. Here, everything is presented to us in stark detail – the story itself is incredibly simple, and the stylistic approach is even more straightforward, which may seem like a negative critique considering what we’ve come to expect from Hitchcock, but it actually becomes quite effective in the context of the story it’s telling, giving it the deeply unnerving, authentic sense of foreboding danger it was clearly trying to achieve. Intricate, but driven by the intention to unveil the many peculiarities of the story, rather than many any bold stylistic statements, The Wrong Man is a very interesting film to watch unravel, each scene bringing a new understanding to the central mystery, adding new layers to what is already a tense, disturbing story of a man whose entire life is teetering on complete destruction, all because he has a passing resemblance to a criminal. We’re rooting for him to get out of this bind, but each detail that we come across points towards a situation where his guilt is more than confirmed in the eyes of the investigators.

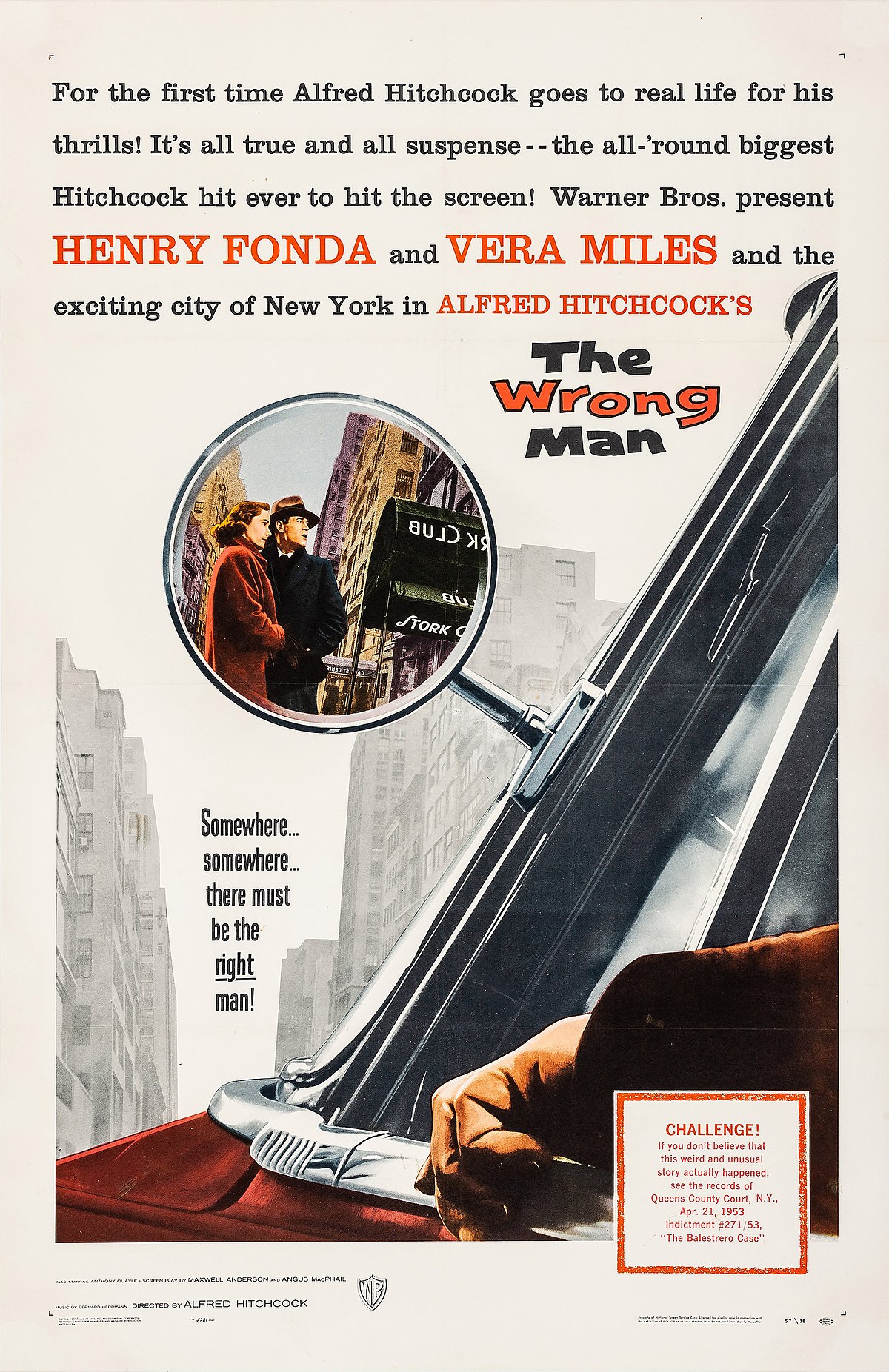

In casting the role of Christopher Emmanuel “Manny” Balestrero, you couldn’t do better than Henry Fonda, an actor who proved himself to be arguably the best charismatic and reliably likeable actor to ever work in the medium (challenged perhaps only by another Hitchcock regular, James Stewart). Considering this film needs the audience to believe in the character’s innocence without any proof, it was important the role was cast with someone we implicitly trust – and Fonda was the perfect candidate, since his salt-of-the-earth charisma makes for a compelling screen presence. While it may not be his finest performance, considering the depth of work he did over his career that spanned half a century, The Wrong Man is a fervent reminder of why he absolutely adore Fonda and revere him as one of the paragons of the Golden Age of Hollywood. He’s measured and deeply captivating, taking on this role with the kind of elegance that he normally would bring to his performances. He works well with Hitchcock’s intentionally vague interpretation of the story of Balestrero, playing him in a way that the audience can easily connect with his struggles, but without making him too much of a victim. Part of the film is that we know that Manny is not a guilty man, but it’s Fonda’s quieter moments that hint at the possibility that what we’re seeing may not necessarily be true, with the glimmer of doubt that comes about in certain moments being one of the director’s trademark instances of misleading us. It ultimately turns out to be for nought, since the final climactic moments of the film prove what an exceptionally interesting case this was, and how Manny faced many obstacles through being mistaken for a criminal – and throughout this entire story, Fonda is absolutely exceptional.

What is perhaps most interesting about The Wrong Man is how intentionally frustrating it is. We know that Manny is innocent – not only is he played by the very principled Fonda, there is clear evidence pointing away from his guilt, despite the film starting long after these supposed incidents took place. There is never any doubt in the viewer’s mind that he is innocent – yet, it seems like only the protagonist and the audience know the truth, while every other character (including his own family after a while) start to have their doubts, even if unintentionally. Hitchcock knows exactly what he is doing – rather than giving us the sweet relief of having the story go in the direction of a happy ending, he intentionally makes each scene more bleak, leading us to believe that the main character would eventually have to atone for crimes he didn’t even commit. Films about mistaken identities are relatively common (Hitchcock himself did a few throughout his career), but this is one where it actually becomes quite disturbing, especially since we want the very likeable protagonist to succeed, but all signs point towards the opposite. The choices the director makes throughout the film are fascinating, since he doesn’t ever surrender to the temptation to heighten the tone or make it more cinematic, instead allowing this very simple story of a man fighting for his innocence and freedom, but losing nearly every battle, speak for itself. It’s made with such razor-sharp precision, it’s very clearly the work of a master – but while this is a Hitchcock film at its core, some of his methods in telling Balastrero’s story shows how he could easily challenge his own style, taking on such a story in a very different way without losing the qualities that made him arguably the finest filmmaker in the English language, at least in terms of setting a foundation for nearly a century of fascinating, suspenseful storytelling.

The Wrong Man is a dark, unsettling portrayal of the flawed criminal justice system, and a demonstration of how the supposed principle of “innocent until proven guilty” is not so much a comfort as it is a hindrance to those who may be innocent, but just so happen to coincidentally bear some traits that conveniently indicate guilt. Paranoia has rarely been better demonstrated in a film than it was here – and through removing all of his trademark lavish humour, and replacing it with a bleak, hopeless image of one man’s descent into sanity as a result of a mere accident, Hitchcock creates one of his darkest glimpses into society, and a film that is likely going to terrify more than it will entertain. The fact that this is based on a true story only makes the central storyline all the more worrying, since this isn’t a work of fiction, but rather a biographical, almost documentary-like account of real events. This isn’t entirely untreaded ground for Hitchcock – anyone with even the most basic knowledge of the director’s work will be able to see his fundamental traits embedded in this film. The difference here is that the tone is slightly more simple, and the execution is a lot more minimalistic, almost being a throwback to the more sinister, looming dangers of his earlier films, where the mood lurking over the story was more focused on an atmosphere of unsettling the viewer and taking us into the heart of a truly disconcerting portrayal of the human condition. It’s not an overly complex film, and it does represent something of a stylistic departure for Hitchcock, who was certainly trying something different here, while still staying within the rough confines of what he is mostly known for, creating a vivid and unforgettable drama with a lot of nuance that only serves to pique the audience’s curiosity even more, and show us an entirely different side of society.