At the perfect intersection between romance, melodrama and fantasy resides Portrait of Jennie, a film that combines all three genres in a particularly beautiful way that has rarely been witnessed, and has allowed it to flourish into one of the more cherished dramas of the 1940s. Director William Dieterle was certainly not a stranger to these kinds of tales, socially-charged dramas that employ deep discussions on folklore and mythology to tell these stories, giving audiences a glimpse into their own lives through the lens of vaguely fantastical means, which are always quite beautifully conceived, even if the quality of the stories may deviate at times. Portrait of Jennie is a remarkably simple film – a young, penniless painter encounters a mysterious girl named Jennie, who is not all that interesting at first glance, but yet he can’t get her out of his mind. Over the next few months, he constantly stumbles into her, each time being absolutely bewildered by how she’s managed to age years in the matter of weeks, which leads him to finally produce his life’s greatest work, the titular portrait, which he hopes can capture the spirit of this young woman who has captured his heart. Simple but effective in the way that all good melodramas should aim to be, and composed with an immense amount of sincerity that shatters boundaries and helps it develop into one of the most progressive dramas of its era (looking at aspects of the genre that were still somewhat revolutionary, even if we’ve grown accustomed to them in later years), and sets a foundation for the kind of beautifully romantic fantasy films that would come to define entire generations, who found the striking imagery of another world coming into contact with our own both puzzling and thoroughly endearing.

Functioning as some combination of James Joyce’s The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (thematically, rather than just sharing the artist motif), this film is a fascinating character study that feels genuinely insightful without being too overwrought, finding the perfect balance between character-driven drama, and bold, emotionally-resonant romance. Dieterle had an interesting approach to these stories, allowing the intricate details to filter through the veneer of simple, quiet meditations on life in its different forms. From the first moment of Portrait of Jennie, we know that what we’re about to see is going to be special – the story may be set over half a century ago, but the premise is one that will resonate with anyone who has felt that deep melancholy when encountering someone for the first time, and immediately knowing that they’re going to have a profound impact on your life. In the case of this film, the relationship between Eben and Jennie is one that resembles less of a romance built on attraction, but a dynamic that exists between an artist and a muse, and how this person changes his perspective and guides him to doing the best work of his life. In the process of recording her various nuances, Eben doesn’t notice how the source of his inspiration is fading away, almost as if she only came into his life as a means to ensure that her memory never disappears – and without spoiling the film, there is a twist towards the end that is truly stunning, and helps the more unconventional aspects of the plot make perfect sense, particularly in how it comes together to create a truly unforgettable image of the artistic process, and how inspiration can not only strike in the most unexpected places, but also leave us profoundly changed in our perspective on creativity.

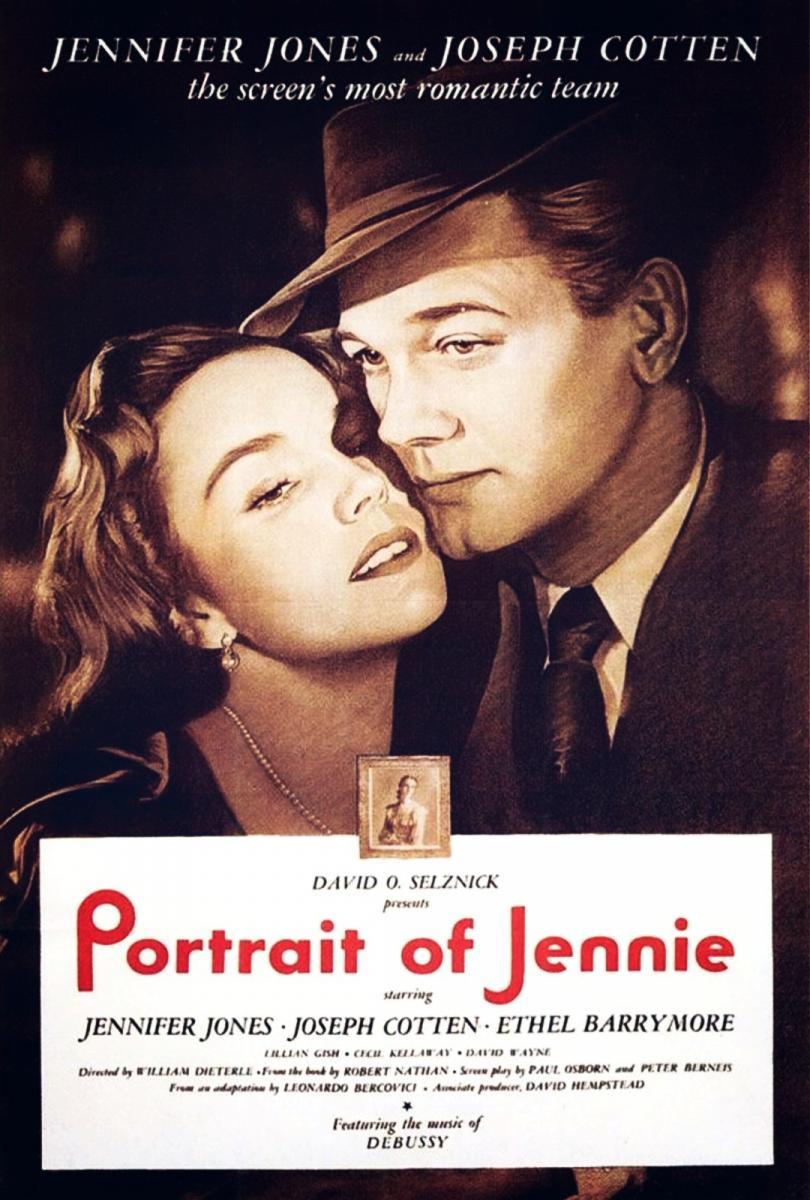

Joseph Cotten and Jennifer Jones make for a formidable duo in the two leading roles. What makes their work in Portrait of Jennie so special is how, despite both being indicative of a particular era in the Golden Age of Hollywood, their sensibilities as actors were slightly different, but they were used effortlessly well here. Cotten is a more down-to-earth, ordinary everyman who can convincingly play a struggling artist, while Jones is the ethereal, otherworldly heroine who is both mysterious and wonderfully forward in how she functions. The film draws on their exceptional chemistry, and even when it isn’t explicitly romantic, there is a spark between them that is difficult to describe. Both are doing impeccable work, and while it’s a peak for neither, the film offers them the opportunity to once again play the kind of reliable, interesting characters they did for decades, and which ultimately defined them as film industry legends. They’re supported by a wonderful ensemble, with Ethel Barrymore (as the art gallery owner who turns out to be a lot more empathetic than her tough, cutthroat persona would suggest) and Lillian Gish (as the older nun who informs Eben as to the truth of his muse) are particular standouts, commanding the screen in their limited time, and leaving an indelible impression that proves what brilliant performers they were, insofar as they could make an impact with such restrictive roles. Portrait of Jennie works because these characters all come across as incredibly human – they’re sincere, honest and always rooted in reality, and credit must go to Dieterle and screenwriters Paul Osborn, Peter Berneis and Leonardo Bercovici, who manage to avoid all contrivances when it came to putting these characters together and using them as emotional anchors for this challenging film.

Portrait of Jennie is a film with a bold premise, and an abundance of emotions – but it still manages to be so seamlessly simple, it’s staggering how the director found the right balance between a high-concept story and the execution of some big ideas that rarely comes across as anything other than truly authentic. This is the kind of film that doesn’t lend itself to enormous analyses or much debate, since it is relatively straightforward in what it aims to say, and remains consistent in how it gradually unveils the pieces of the puzzle that awaits us on the other side of this gorgeous melodrama. Superbly acted by Cotten and Jones, who are charismatic enough to carry this film all on their own, and written with a sense of poignancy and urgency that contrasts with the more ethereal, meandering fantasies that underpin the film, Portrait of Jennie is a truly exceptional glimpse into the artistic process, one that may be more sobering than it is motivating, but still carries a spark of inspiration that only grows to mean even more as we venture into the world and understand the message. In theory, this isn’t a major work, being very little more than a run-of-the-mill romantic melodrama with some daring dashes of fantasy thrown in to differentiate it from other similarly-themed films – but it’s in the execution, where every frame carries a deeper meaning, that we see the real meaning coming through. Dieterle’s work is clean, coherent and compelling, and he never aims to do too much, understanding that everything being kept at an accessible level can only help heighten the experience and make Portrait of Jennie all the more enthralling, since we can all relate in some way to the existential paradoxes that form the basis of this delightfully sweet, and triumphantly meaningful, drama about the very nature of artistic expression, and the different ways we tend to find inspiration.