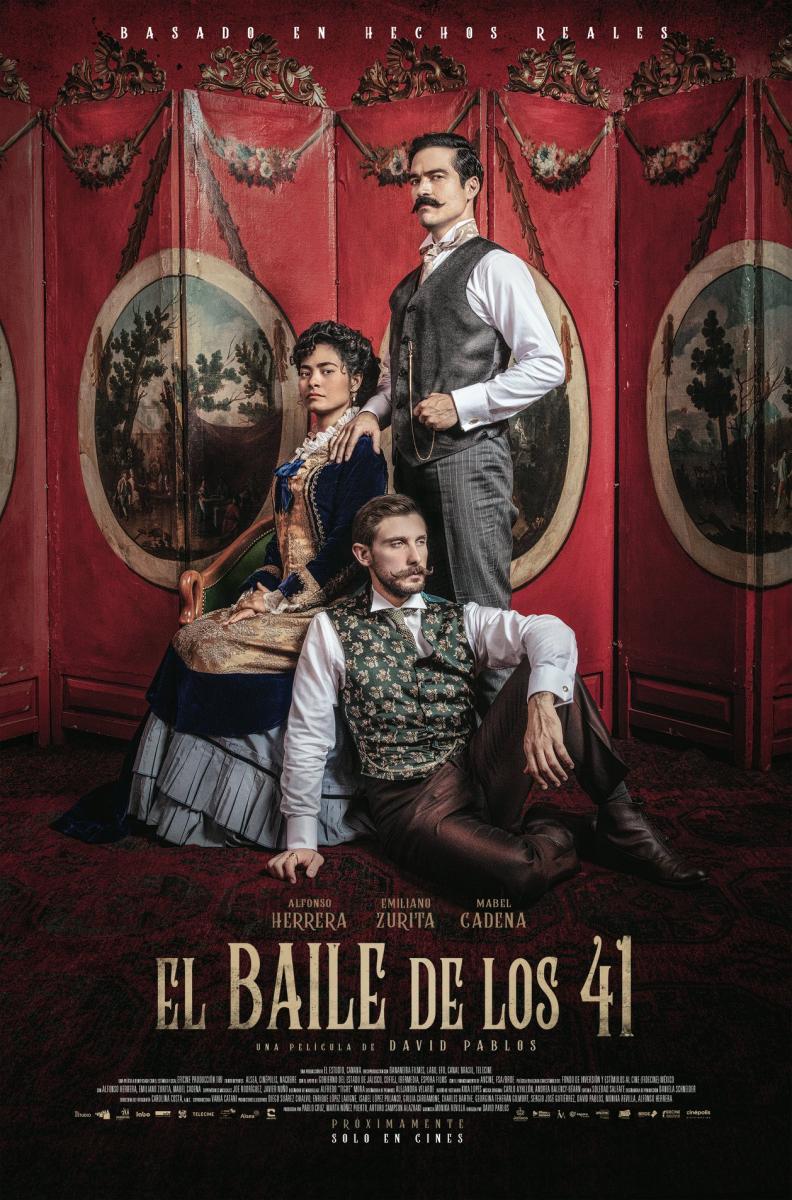

One of the main areas in studying queer history is to obviously look into the past, and see how certain events shaped national and global perceptions of issues relating to the LGBTQIA+ community. One of the most significant moments came in 1901, in what is referred to as the Dance of the Forty-One, where a few dozen prominent members of Mexico’s high society were caught engaging in what was cited as immoral actions, after a police raid found them taking part in a dance, roughly half of them dressed in woman’s clothing. It was a national scandal, and the first major moment in Mexican history in which homosexuality was openly spoken about, albeit in a way that tarnished the reputation of these men, who were not only stripped of their status as a part of the country’s elite, but also lost their freedom, being forced to become a part of the violent conflict known as the Caste War of Yucatán. This story is the subject of the Dance of the 41 (Spanish: El baile de los 41), the stunning but heartwrenching examination of queer issues and the role they played in defining the identities of many people in conservative Mexico. We’re taken into the past by director David Pablos, who captures both the time and place through gorgeous, meticulous filmmaking, which serves as the foundation upon which much of the harrowing social commentary is built. It’s a very simple film, one that isn’t too far from the conventional period dramas we see produced every year – but there is still something quite special about Dance of the 41, a quality that is difficult to explain, but comes about as a result of a very intricate understanding of this historical event, and the wisdom on the part of the director to frame it as less of a stifling period drama, and more of a poignant examination of queer issues in a time when they were not only rarely spoken about in public, but also a subject that could easily have even the most esteemed member of society thrown from the good graces of the conservative culture that dominated the nation at the time.

The continued exploration of queer issues in the media have allowed for a much wider scope of stories to be told, whether historical accounts or fictional composition that all centre on issues of identity and the role societal conventions play in how one expresses themselves. Some of the most fascinating are films that look at real-life events, and use this as a platform to explore these issues. When deciding that the notorious scandal that swept through Mexico at the turn of the 20th century, Pablos found a way to combine both the fascinating biographical context with a deep, insightful exploration of issues of identity. The story of a group of men who had to endure the scorn of a very heteronormative society, and were only able to express their innate, human desires far from prying eyes, makes for a beautifully poetic, but also deeply unsettling, portrayal of life under an oppressive social regime, one driven less by political ambitions, and more by the culture’s inability to look beyond the status quo. Dance of the 41 is an exceptionally compelling film, and while it may not be wholly original in its approach, functioning as a beautiful but somewhat conventional historical drama, the subtext that persists throughout is worth paying attention to, especially when it becomes clear how this isn’t merely aiming to be a retelling of the titular scandal. This is a multilayered look into the trials and tribulations of the people who were forced to hide behind a facade for most of their lives, going about their daily activities in a way that was little more than a socially mandated masquerade, with their only escape being the solace of a group of similarly-minded men who have experienced the same struggles. It’s not a film that pays too much attention to hiding its intentions – there aren’t any enormous revelations, or major betrayals – it’s simple a poignant exploration of identity in the midst of draconian cultural conventions, and the struggle many had when trying to express themselves in a way that was genuine to who they are, but also analogous with the standards of their society.

In constructing this film, Pablos makes some very interesting directorial choices, all of which come down to how he presents the binary lives of the main characters. At the surface level, the film seems to be a suffocating period drama, filled with gorgeous gowns and lavish production design. Most of the “daytime” activities are filmed as these elegant, colourful affairs, filled with luxuries and excess – these moments are the definition of stifling decorum, and supposedly where everyone would aspire to be, since it indicates wealth, influence and, most importantly, unrestrained power and immunity from the scorn of the outset world – it’s not the most entertaining life, but it’s the one that is most acceptable. This is contrasted sharply with the alternative, the scenes that focus on the secret lives of these characters, and their activities that occur behind closed doors. Dimly-lit rooms, where the debonair tuxedos are replaced by the supposedly ungodly sight of human flesh, and where unmitigated, wild passion overtakes political and social ambition. It would’ve been so easy to allow this film to descend into explicit demonstrations of carnal desire (and there are moments where it comes dangerously close), but the director is aware of the importance of a balanced contrast, and on both the narrative and visual level, Dance of the 41 is brimming with such powerful commentary through the juxtaposition of the two conflicting lives, the public persona and the internal identity, as filtered through the perspective of one man, Ignacio de la Torre y Mier (played beautifully by Alfonso Herrera, who commits fully to bringing this character to life), the young congressman and son-in-law to the President of Mexico, who falls victim to his desires, despite being the one person in this society with the most to lose. Using his crisis of identity as the basis for the film is very smart, since not only is he the one character to who we are most connected, by virtue of his status, his oscillation between identities encapsulates all the major themes of the film.

If there is one component of the film that should’ve been executed better, it’s the relationship between de la Torre y Mier and his wife, Amada, whose marriage is central to the film, and the emotional concept on which much of the story hinges. Both Herrera and Mabel Cadena, who plays his manipulative wife, are impeccable actors, but the film seems to focus too much on the marriage of their characters, which may be interesting, but not enough when put in contrast with the queer storyline. However, it’s not so much the content of these scenes as it is what they represent in the grander scheme of Dance of the 41. It’s almost as if the film is indicating that this heterosexual relationship – which de la Torre y Mier ultimately returns to after being caught for his deviancies – is normal. It was conventional, but it wasn’t necessarily the salvation this story warranted. Cadena is phenomenal, but she can only do so much to avoid being shown as the victim, and the film doesn’t do much to frame her positively – first she’s a naive young ingenue, followed by a vindictive, scorned wife, and then in the third act, she finally comes into her own as the saviour of the main character, which is when she actually gets something meaningful to do, rather than just being a scorned wife. Ultimately, framing the queer aspects of the film through the lens of the wife trying to make sense of it may seem like an interesting angle, but not at the expense of the more captivating sequences that occur in the characters’ private lives. So much of Dance of the 41 is built on emphasizing the duality of the main character, the only flaw would be that it deviates from it too often, especially at key moments. However, this is a minor issue, and really only distracts from the film on the most minuscule level, particularly when the story manages to develop both sides equally well, creating a striking balance between the two that is truly stunning when viewed together.

Dance of the 41 is a film that is easy to overlook. At first glance, it is quite unassuming, and even if your curiosity is mildly piqued by the promise of a sweeping romance set to the backdrop of a historical period, in which we’re invited to luxuriate in the splendour of the past, it’s difficult to fully prepare for what we’re about to see. Pablos has made an absolutely spellbinding film that combines political drama, historical epic and poetic romance, and returns a truly unforgettable story of identity politics coming into collision with sacrosanct beliefs. It should be noted that Dance of the 41 is a very visceral film – there are moments of intentionally explicit passion, as well as some very haunting subject matter, which proves that this was attempting to not only be an account of the real-life scandal, but also a powerful, heartwrenching exploration of sexuality, and how one’s desire to self-express can be stifled by external pressures that force them to act in a certain way and abide by social conventions that are immovable, and the many people who maintain these principles, some of them doing so to distract from their own deviant behaviours. We become fully immersed in this world, and watch in both awe and horror at how Pablos represents this dark moment in Mexican history. Dance of the 41 is a challenging film to watch, and it can often be excruciating, especially in the final few moments, where we see a different kind of viscerality. This is a film that is about both passion and suffering, and while it may struggle to find its voice from time to time, it is still an astonishing work and a film that deserves a great deal of attention, since not only is it a stunning work of contemporary filmmaking, but a vital story that should be experienced by those who may not be aware of these events. The only way history can avoid being repeated is through awareness, and while this may seem like a minor effort, it brings to light this dreadful scandal, in the hopes of avoiding such a horrifying betrayal of fundamental human rights ever again.