From a contemporary perspective, Woody Allen is a bit of an anomaly, since he is someone who has developed into something of a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to working in many different genres, but he’s still retained his distinctive authorial voice behind the camera, one being able to recognize one of his films without much effort, since they all share certain similarities. His output in the 1970s was fascinating, since most of his defining comedies were produced in this era, extracted from his experience in the field of broad humour, which he was slowly sharpening into more profound explorations of the human condition. This took a sharp turn in 1978, when he made Interiors, his first straightforward drama, and still perhaps his most grave and serious film, even if he has ventured into the realm of the dramatic on a few occasions since. A beautiful and poetic story that looks into the lives of a small group of characters as they come to terms with some of life’s harsher realities – falling out of love, the inner insecurities of not having any direction in life, and one’s own mortality – and facing the daily challenges that each of them come across in their daily lives. Delicate, heartwrenching and brimming with a very distinct energy that allows it to be profound without even a slight hint of sarcasm or irony anywhere to be found in it, Interiors is a marvellously captivating film from a director who successfully pushed himself to try something entirely new, and started an even more impressive run of films, where the humour could be sidetracked in favour of some devoutly human stories.

Allen’s first foray into more serious subject matter is also his most successful, as it is his most complete work in terms of drawing out the fragile melancholy of existence, which he miraculously does without hinging on his comedic background. In recent years, the director hasn’t been known for his impeccable quality, throwing out a film nearly every year, of varying quality. However, his earlier work suggests that he was a fascinatingly creative artist, as can be seen throughout Interiors. The director himself has stated that he drew from two major sources as his inspiration – the work of Ingmar Bergman (who Allen would often use as a cultural touchstone for many of his upcoming films), and the great American playwrights, who used familial structures to hint at the darker depths of modern existence, with Eugene O’Neill in particular being a major influence on this film. Allen is often written off as someone who defaults to the same style, but his curiosities are often some prescient in the earlier stages of his career, where he demonstrated a keen sense of ambition to tell stories in a way they hadn’t been done before. Interiors is his method of staking a claim at the great American tragedy, the kind that captivated audiences for decades on stage and screen – and refusing to do an adaptation (Allen, for all his merits, is far too hubristic to directly adapt the work of anyone else), but rather craft his own version of the myths that surround the trials and tribulation of the upper-middle-class, the director pulls together various narrative threads and weaves them together into a heartbreakingly earnest and deeply unsettling portrait of a family in crisis.

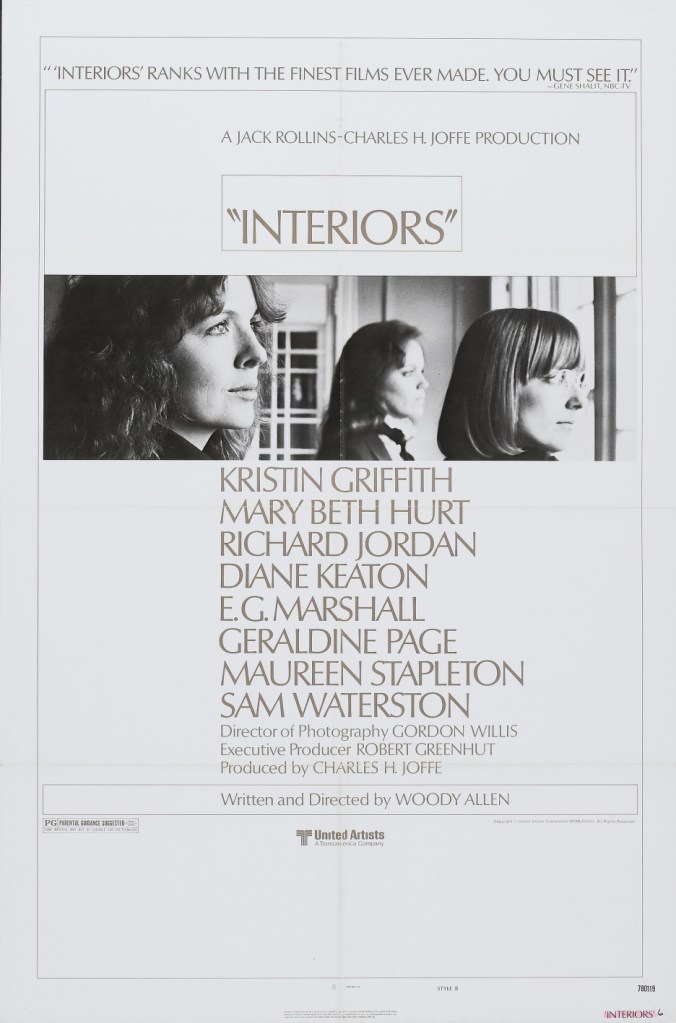

Coming the year after Annie Hall, by far the director’s most successful film in terms of critical and commercial performance at the time,meant that Interiors was built on a foundation of audacity, with Allen choosing to deviate into the purely dramatic. Accompanying him along the way is Diane Keaton, whose performance in the aforementioned romantic comedy classic made her an instant icon. Unlike Allen, Keaton had years of experience in drama, and brought with her a set of distinct skills that help make Interiors as compelling and believable as it was. Playing the role of Renata, she is stoic and quiet, the polar opposite of Annie Hall, a woman whose eccentricities and exuberant personality made her quite a formidable contrast to this poet amid an existential crisis. Mary Beth Hurt is just as good, playing the insecure younger sister who is trying to find her place in the world, but is filled with such resentment for those who have, she continuously fails to achieve anything other than unhinged bitterness. Allen looks deeper into the familial structure but forming a story around mother-daughter relationships, one where the maternal figures are far more interesting, and the daughters are intentionally constructed in a way that makes them seem more ambigious. As a result, the two most memorable performances come on behalf of Geraldine Page as the girl’s biological mother, a depressed and lonely interior decorator, and Maureen Stapleton, as their new stepmother, a far more personable woman whose joie de vivre compensates for her lack of refinement or deportment. Interiors is a true ensemble effort, but it’s these two veteran actresses who prove to leave the most lasting impression, their equally poignant but wildly different forms of elegance setting the basis for a wonderfully compelling character study.

As it stands, Interiors is one of Allen’s most unique works, and also the one that sees him asking far more probing questions than we’d expect from someone who normally traded in excessive comedy. Intimate and often quite frigid, the film truly lives up to its title in more ways than one. On the surface, this is a film about places more than people – virtually the entire film takes place in the homes of these individuals, each one of them lovingly decorated by Page’s pernickety but dedicated character, who has gone to great lengths to treat each room like a sonata, beautifully composed, but often very cold and formal. Looking slightly deeper, we realize the interiors of these homes reflect the inner-states of these characters, each one of them coming to terms with their own failures and working through their personal quandaries while trying to be productive members of a family that would like to think of themselves as quite loving, an endeavour each and every one of them doubtlessly fails at. Allen works very hard to convey the inner turmoil of these characters – they’re designed to be likeable enough to not repulse us, but not with a level of charm that allows their abhorrent behaviour to be excused. We’re often watching in annoyance at how each of them squanders every opportunity to redeem themselves and strengthen the bond with the people they have grown to resent. They all want to reach a place of happiness, where their animosity isn’t driving them apart – but when they are too selfish to realize their own flaws, and instead go about masquerading as the victim (rather than the perpetrator of this tension, which all of them are), all hope of reconciliation disappear – and it can only take a major, but inevitable, tragedy for them to realize what truly matters.

Interiors is a tremendous film, and one that wears its heart on its sleeve where it matters. Allen’s style is distinct and compelling, and he brings such a depth and honesty to a story that could’ve so easily just been a bland, unconvincing attempt at serious dramatic work. He carefully removes all humour in such a way that shows the gravity of the material without making it dull or meandering, and instead constructs a profound exploration of a family’s decline over the course of a few months, watching them react to various crises while trying to maintain their composure, yet another area in which they don’t succeed. Allen took a risk with this film, and it certainly paid off, since the final product is a brilliantly subversive look into some common issues, presented in a way that is both bleak and engrossing. It proves that he is one of the finest writers to ever work in the medium of film, as well as an artist who doesn’t depend on only his strengths when it comes to curating his craft – he can easily try something entirely new and succeed. Inarguably, many of his later dramatic efforts are much weaker and far from as convincing as this – but considering how Interiors was produced at a time in which Allen was actually taking an active role in the medium, rather than resting on his laurels, it’s unsurprising that his first attempt at drama would be his most compelling. Intricately-woven, beautifully filmed (kudos must be given to Gordon Willis for his stunning cinematography), and written with a precise candour, Interiors is an astonishing and staggering work of fiction that leaves one both awe-inspired and undeniably frustrated, a winning combination when trying to cut to the core of the human condition.

In 1978, Interiors was divisive. Some who adored Woody Allen felt betrayed by his embrace of a drama. Watching the film in the theaters was frustrating as so many walkouts noisily disrupted the somber mood. It was as if the disenchanted felt Allen himself could hear their disrespect as they left.

For those of us who adored Interiors in 1978 and saw it repeatedly during its run, we marveled at the stunning cinematography of Gordon Willis. There is a shot, I believe it’s in the beach house, of three disparate yet alike vases that echoes in the famed shot of the three daughters staring out to sea. That seemed to be a defining moment for audiences. You either accepted the notion that the sparsely decorated home and its minimalistic design was a commentary on the lives of these women or you rejected it. And I do mean women. Men, even E. G. Marshall, are irrelevant in this tale.

I believe it is in this film that Allen became the extraordinary artist who created complex roles for women. Eve and Pearl are assumed to be so different. I think they are rich roles that show us how easy it is to allow our experiences to shape us emotionally. Our choices in life will define our self perception. These choices and experiences prompt us to wear the vibrant red dress or the tasteful, muted ensemble. Both Geraldine Page and Maureen Stapleton were duly celebrated for magnificent performances.

For a man whose private life is a maelstrom of misogyny and moral indiscretions (at best), Allen’s art celebrates and reveres women. He has earned a whopping 16 Oscar nominations for Best Original Screenplay and no less than 11 female characters that delivered Oscar recognition to the actresses who played them. That astonishing record really begins here. For it begins in Interiors where we are compelled to acknowledge the on-going humanity of the women in Allen’s film. These women are invariably angry, funny, intelligent, and articulate. Perhaps that was the greatest thrill in watching Interiors in 1978. The noticeable absence of substantial female characters in film during the 1970s had led to serious consideration of eliminating the Oscar for actresses. Interiors rose up to remind audiences and other filmmakers that women were fascinating and vital. In that effort alone, the film was revolutionary for its day.