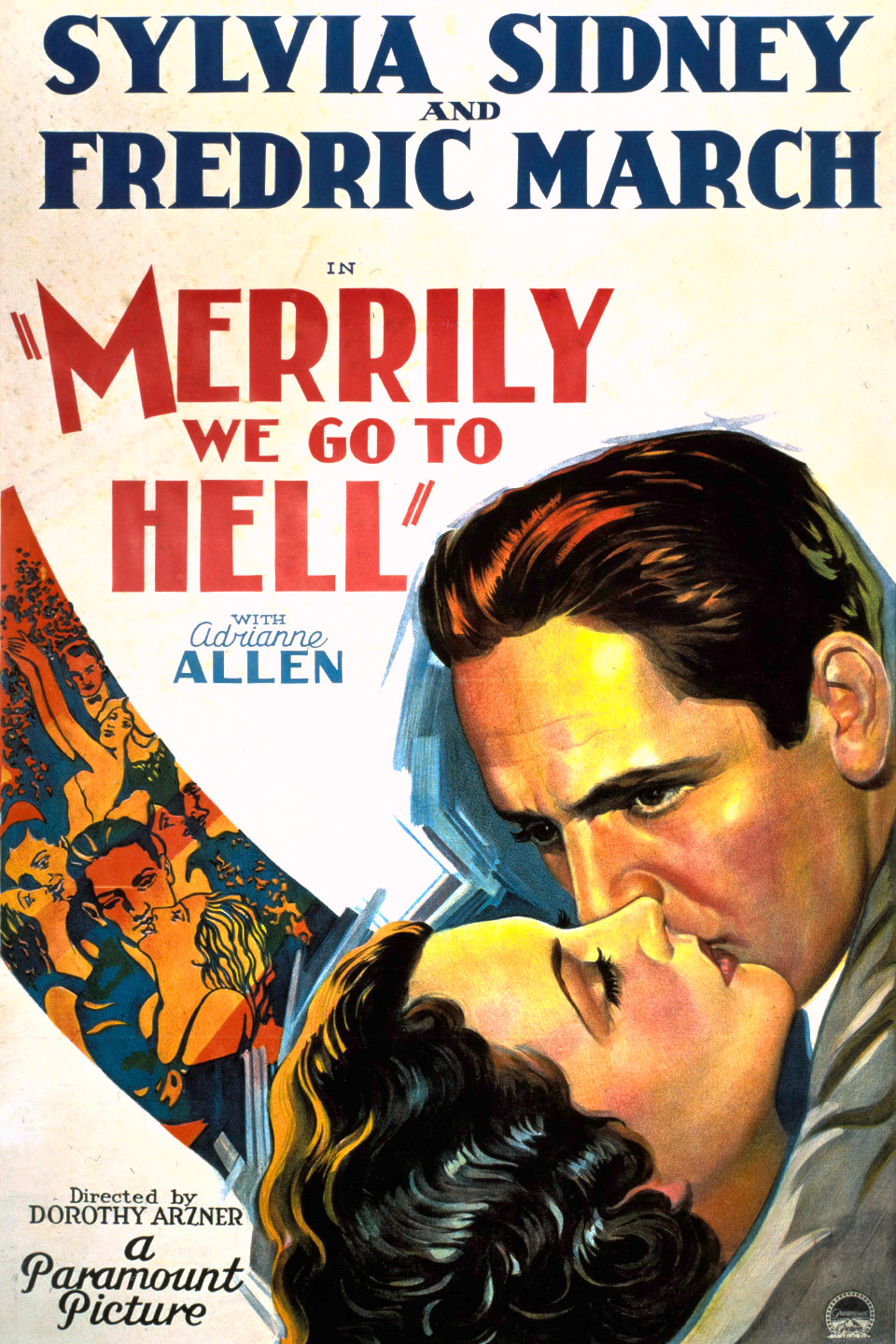

Over the years, I’ve spoken openly about how certain female filmmakers were revolutionary, particularly those that worked in decades when film was even more dominated by men than it is today. Gender politics have been an enormous part of Hollywood culture, and it is an issue that is slowly being resolved, but not nearly fast enough. However, of all the incredible women that have taken their place at the helm of a wide variety of films, there is one in particular who is the ultimate pioneer, at least in terms of American filmmaking – the incredible Dorothy Arzner, widely considered the first influential female director, and someone whose work has recently started to gain the acclaim it deserves, with the general consensus being that the director was a forgotten maestro in an industry where she was not necessarily compatible with the idealistic version of a film director at the time. An artist of immense historical importance, Arzner set a foundation for nearly a century of filmmaking, and her best-known film is the topic of today’s discussion, the unforgettable Merrily We Go to Hell, her brilliantly caustic satire that blends romantic comedy and soaring melodrama to be one of the most pointed critiques of broad social issues ever committed to film. Ahead of its time in the way that only the most deeply subversive texts tend to be, and absolutely stunning in both theory and execution, Merrily We Go to Hell thoroughly earns its growing status as one of the defining films of its era, and one that continues to leave a profound impression, especially as we start to look beyond the specific patterns that dominated during the Golden Age of Hollywood, and see the revolutionaries that were hidden in plain sight, thriving as they asserted their vision on an industry that may not have been ready for it, which only makes them all the more charming and effective from a contemporary perspective.

The Pre-Code era normally evokes ideas of edgy subject matter, films that cover topics that were far more controversial, with filmmakers managing to get away with depictions of ideas that would soon fall victim to the studio system, which essentially banned anything that didn’t fit with their myopic, falsely-idealistic perspective of what audiences could appreciate and enjoy. However, on occasion, you tend to find films like Merrily We Go to Hell, one that may be relatively simply in premise, and not filled with anything particularly controversial at a cursory glance – after all, the film is centred around two young people falling in love, getting married and realizing the challenges that await those entering into this sacred union. However, the deeper we look, the clearer it becomes that Arzner and her cohorts were functioning at a profoundly subversive level, taking every convention that dominated at the time in regards to these simple romantic dramas, and dismantling them, exposing their convolutions and shortcomings, while rebuilding it through their own artistic perspective. The director takes on the material (extracted from the short story “I, Jerry, Take Thee, Joan” by Cleo Lucas), and turns it into one of the most deliriously twisted dark comedies of this period, a film that is relentless in its sardonic portrayal of modern marriages, and doesn’t avoid openly criticizing gender roles in a time when anything remotely deviant from the heteronormative structures was considered in poor taste. Arzner didn’t take on the reputation for being one of the most provocative filmmakers of her era without reason – and as demonstrated throughout Merrily We Go to Hell, she was capable of scathing commentary that would be shocking even by modern standards. This is the joy of the Pre-Code era – under the laissez-faire policy of artistic expression, anything goes, and Arzner certainly wasn’t one to pass up this particular opportunity to both shock and delight her viewers.

At the centre of Merrily We Go to Hell are two incredible performances by a pair of the most gifted actors of this era. Frederic March, the eternally charming everyman with a sinister streak, is the anchor of the film, playing the good-hearted journalist who struggles with addiction, to the point where it begins to erode his domestic life, and puts him on the verge of a complete breakdown. Sylvia Sidney is the beating heart of the film, the emotional foundation on which most of these interactions are built. Strikingly beautiful, and brimming with a tender confidence that persists throughout the film, she commands the screen, going toe-to-toe with March, who is playing a very broad character, but has the good sense to move aside when it is Sidney’s turn to leave an impression. The duo are just incredible, and turn in some of the finest performances of the era. The key is that neither one of them is representative of the one-dimensional leading character that was commonly found in both comedies and melodramas from this time, developing them far and beyond the confines of the archetypes. Jerry might be a lothario who finds his downfall is always at the bottom of a bottle, but he’s far more than just an alcoholic, but a fully-formed man who struggles to overcome his addiction. In contrast, Joan may be the wife who has to endure a spouse who grows increasingly hostile as a result of the toxic combination of a violent addiction and the overt masculinity that causes him to lash out in various ways – but she is also someone with a solid grounding, rather than one who simply sits and observes her life falling apart. Both actors are delivering absolutely stunning work, holding our attention with their beautifully realized interpretations of these characters, who are constructed with such sincerity, you’d think Arzner was working from a place of profound experience in understanding these kinds of people.

It’s always an absolute delight to see a film where as much care has been put into developing the characters as there was to telling a memorable story, and Merrily We Go to Hell certainly achieves both with remarkable consistency. The film is drawing from a set of notable genre tropes, employing ideas from romances, comedies and melodramas in equal measure – but the effect doesn’t come in how it draws from some popular genres, but instead how it seamlessly assimilates these concepts into the fabric of what is essentially a very realistic story, touching on issues of a “modern marriage” (predating the now-acceptable concept of an open marriage, which would’ve been unheard of in the puritanical years of idealistic, heteronormative values) and addiction. It certainly doesn’t avoid taking a few artistic liberties for the sake of dramatic effect, such as in how it toggles between the genres to keep us captivated. Yet, what we’re drawn to is not the most delightful joke, or the moment of most profound suspense, but instead the simple reflections on reality, the small observations on human behaviour that become almost uncomfortable in how realistic they appear to be. Despite being made nearly a century ago, Merrily We Go to Hell is still a very pointed critique of social mores, the kind that are accepted on principle, but never questioned otherwise, since doing so would disrupt the perfectly calibrated order that so many have laboriously tried to maintain. Arzner was not one to play by the rules in any way, so her careful manipulation of conventions, and deconstruction of what is considered to be acceptable, becomes quite profoundly disturbing, while still being extremely effective. These characters are not villainized for falling victim to the disease of addiction, nor are they reviled for their marital indiscretions – the film doesn’t condone their actions, nor does it show them as absolved of all consequences – instead, it paints a compassionate picture of how everyone has their flaws, which should be resolved through introspection, rather than rejection.

Exploring the endless depths of the Pre-Code era often yields conversations about how certain films were ahead of their time, and this particular period allowed for these edgier, more subversive stories to filter through, setting a foundation that wouldn’t come to be used again in mainstream American cinema for nearly half a century, when New Hollywood emerged and picked up where these films left off. Merrily We Go to Hell is a fantastic film, one that is absolutely brimming with a unique energy that feels very well-placed in this particular version of the world it is evoking – one that harbours many sinister secrets, but also a sense of joyful exuberance, where optimism may seem foolish when you’re confronted with a haunting reality of addiction, marital strife and psychological turmoil, but if one is able to push through this, there’s nothing but bliss awaiting them on the other side. Arzner was a revolutionary filmmaker, and her work reflected a keen understanding of the human condition – and looking at some of her more notable curiosities through the lens of both a darkly comical satire and a romantic melodrama, only aids in heightening the message and bringing out a new set of ideas that had previously not been seen before, at least not in as bold a form as here. Merrily We Go to Hell is simply an exquisite piece of filmmaking, anchored by two extraordinary performances, written with honesty and integrity, and directed by someone who understood the intricacies of the assignment, so much that she made an indelible impression on an industry that owes her an enormous debt, and which has only started to be realized over the past few decades, when her legacy became abundantly clear, and her career warranting nothing but the most sincere celebration and adulation.