It doesn’t take an expert to realize that the films of Yasujirō Ozu tend to follow familiar patterns – the majority of them focus on working-class Japanese citizens in various cities around the country, coming to terms with their own personal quandaries in the years preceding or following the Second World War, which wrought irrevocable damage on the nation’s culture, which took several decades to fully recover from – and yet, each one of them is so starkly different in their own way. Ozu was a master storyteller, and could create some absolutely spellbinding works as a result of his simple style and ability to bring out the emotion in absolutely any project, regardless of how it may tread through familiar narrative territory. As one of the most prolific filmmakers of his generation, Ozu was bound to have some films that aren’t as widely appreciated as others, which isn’t indicative of their overall quality, but rather that audiences may not have responded with the same resounding warmth as some of his others. Tokyo Twilight (Japanese: 東京暮色) is a fascinating film, because it both defines these principles, while still going against most of them. It’s a strangely enticing melodrama with an acidic edge that many of even the most seasoned Ozu devotees might find somewhat jarring, since it is so unexpected to see a director who epitomizes warmth and elegance, producing something so dark and brooding. However, it all works in the favour of this film, which dares to be different exactly where it counts, as well as knowing where to hinge on its director’s tried-and-true methods, creating a fascinating portrait of society that could really only come from one as gifted as Ozu.

In a career as varied as Ozu’s, choosing a favourite is nearly impossible – but if there is one film that most encapsulates what the director was capable of, it is Tokyo Twilight. The kind of film that doesn’t immediately announce itself and all its intentions from the start, but rather one with a very particular modus operandi, brought to life through a collision of the director’s pared-down style of overt simplicity, with some more serious conversations that are woven into the narrative. In Tokyo Twilight, the cheerful melancholy that often defines Ozu is almost entirely dismissed, relegated to a few short scenes peppered throughout the film (most likely there to lighten the tone when it is at its most uncomfortable), and the director operating from a space of profound despair and deeply unsettling sadness. This is an exceptionally sad film – Ozu is not any stranger to showing tragedy on screen, but there’s something so incredibly bleak about how this story transpires that makes it something of an outlier, a film that goes about unveiling the layers of a story that is already quite downbeat at the start, and only spirals into more existential angst as it forges a path forward. Tokyo Twilight was certainly not the first time Ozu would look at themes such as broken relationships, absent parents or the death of loved ones – but it’s one of his most potent experiments in each of them, bringing out the meaning, even after we genuinely believed there wasn’t anything else to decode from this material.

Yet, even with this slight change of pace, Ozu is present in every frame of Tokyo Twilight. This film is undeniably his work – and whether it’s clear from the presence of his repertory cast, or the very distinct narrative beats that are inescapable in his work, or the general tone that balances seriousness with moments of light humour, as a way to break the tension and put the audience at ease once again. Ozu was rarely as bleak as he was in the process of putting together Tokyo Twilight, especially considering how this film would be followed by half a dozen masterpieces that blend comedy and drama together perfectly. Yet, even when he was doing something quite haunting, there was a precise beauty to his work that allows us to know that we’re in safe hands. Even if he intends to put us through the emotional wringer, Ozu is fully in control of the narrative, and knows how to play to the rafters when it’s necessary, as well to scale it down to the most fundamental human level. It’s this tonal balance that helps justify the darkness of Tokyo Twilight, since it isn’t depending on the audience feeling sympathy, but rather to take a bold and unsympathetic stance to the reality of the situation it depicts – we’re compelled to feel empathy, but in a constructive and authentic way, where we come to see the truths that underpin the story, rather than being manipulated to feel something by the emotional construction of the film. Ozu’s ability to make us feel the full spectrum of emotions through the most simple methods are just further proof that he is one of the finest filmmakers to ever work in the medium.

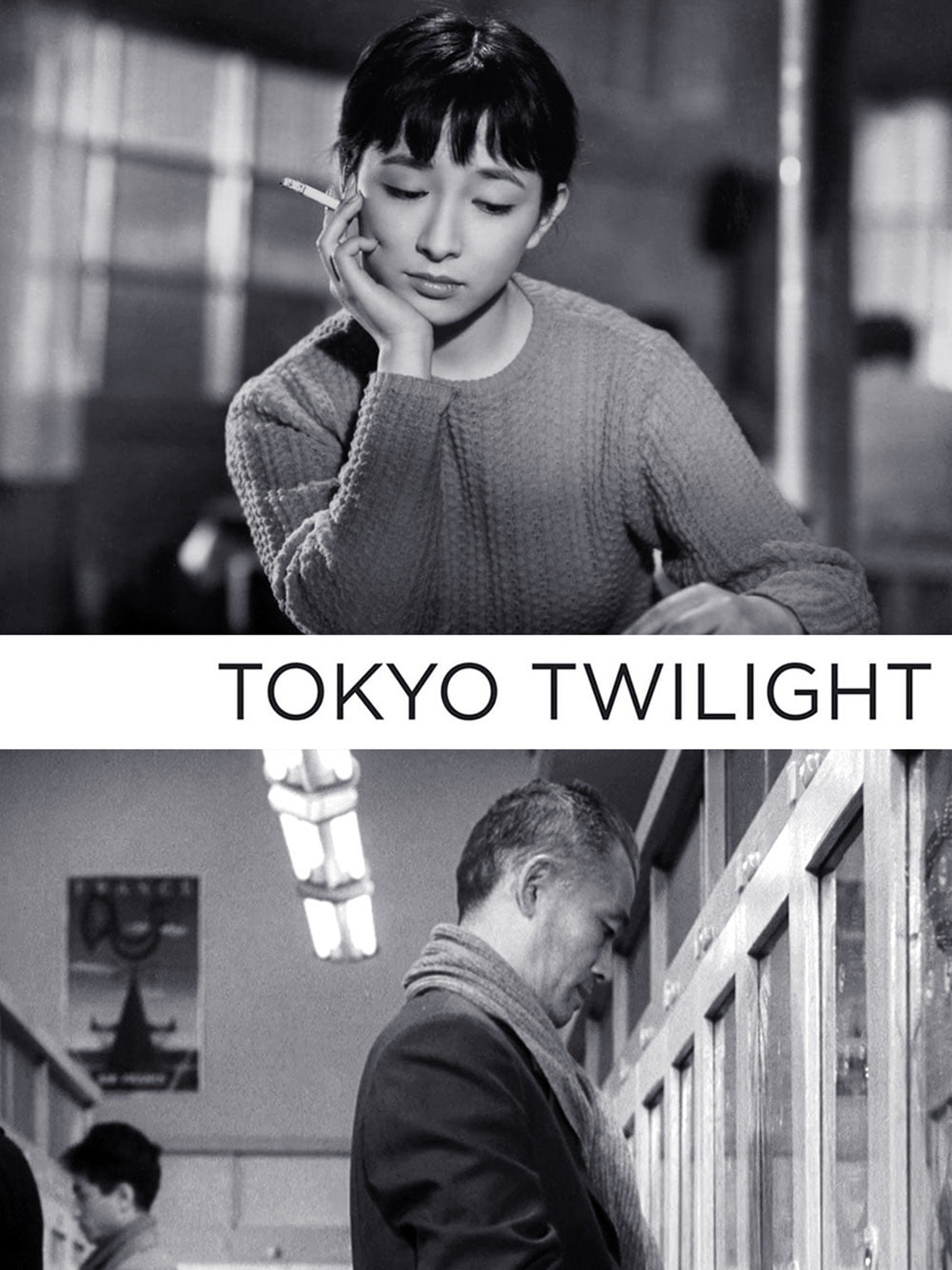

In bringing these characters to life, Ozu mostly makes use of a regularly rotating group of actors, who all seem to be raring to work with the esteemed director again. As far as mid-century film icons go, you can’t do much better than the beguiling Setsuko Hara, who wasn’t only an effortlessly gifted actress in the traditional sense, but also possessed the ability to say so much without uttering a single word, her expressivity and movements conveying more than words ever could. She is absolutely exceptional in Tokyo Twilight, but it’s her chemistry with the rest of the cast – particularly the two other female characters – that makes this an absolutely masterful entry into Ozu’s canon of great achievements. Each one of his film centres on one particular theme, which remains relatively prominent, regardless of where the narrative or tone shifts – and in Tokyo Twilight, the theme of motherhood is explored in depth. It’s realized through Hara’s relationship with her younger sister, played with simmering intensity by the beguiling Ineko Arima, with their dynamic being one very much of an older sister taking on the maternal role for a sibling. Their chemistry is impeccable, and we genuinely start to believe they are sisters throughout the film. The entry of Isuzu Yamada as a mysterious woman who turns out to be their biological mother only complicates matters, and presents the film with some deep, insightful commentary on the experience of encountering someone as pivotal as your parent later in life. Yamada is covertly giving the best performance in the film, the aching melancholy of a mother who was forced to abandon her children being reflected in her beautiful and complex portrayal of the character, and her introduction signals the start of a very compelling series of heartbreaking discussions between her character, her two daughters, and a range of other peripheral characters woven into the film.

Ozu made films that followed a familiar structure, and whether you are a new viewer of his work, or a seasoned veteran, we know more or less what to expect. However, this doesn’t mean he was a director defined by any kind of laziness or insincerity to the material, since each one of these projects does something different. Tokyo Twilight is certainly one of his darkest films, and seems to be almost entirely void of the upbeat charms that define even his most melancholy works. Yet, it doesn’t feel so much like an outsider as a slight deviation into more complex narrative territory. Not only is Ozu exploring the theme of motherhood from a more depressing perspective, whereby two young women come to know their mother very late in life after having grown up without the nurturing care that a loving parent can bring (their father, while dedicated, was not always up to the task), but the director is also making some bold statements on a range of other issues. Abortion is a central theme to the film (Japan was one of the first countries to legalize terminating a pregnancy, long before most other countries), as is the concept of mortality, especially regarding those who are much younger and find themselves falling victim to particularly harrowing circumstances. It all contributes to the multilayered nature of the film, which gradually becomes more complex and labyrinthine in its exploration of certain issues as it goes on, while still keeping with the effortless simplicity epitomized by Ozu, who was doing some of his most compelling work in this masterful film.