A brief personal story to preface this review – when watching The Remains of the Day recently, I was struck by memories of a very particular time in my life, probably somewhere in primary school. Whenever the question would come up in class about what we wanted to be when we grow up, my classmates’ answers of “astronaut” and “fireman” would never impress me, and I would confidently stand up and proclaim: “I want to be a butler”. In retrospect, it’s an amusing anecdote (and one that perhaps indicates how I was different from a very young age, quite worryingly so), but also one that I think fondly on, since there has always been something about that line of work that has fascinated me. Instead of starting with some deep discussion on the roots of servitude represented on film, it was more important to mention how a film like this has a deep connection to my interests, even if only on the superficial level, and through the lens of childhood naivete. The joy at seeing works of art that paid tribute to this career isn’t to be underestimated, and through some very impressive writing, Kazuo Ishiguro successfully wrote perhaps the definitive text on the subject, which was subsequently turned into one of the finest films of its era, by a filmmaking team that is historically known to be the most impressive when it comes to making period stories. The Remains of the Day is a masterful film, and not only one that earns its reputation, but more than exceeds every expectation going into it. A fascinating journey into the life of a man who has dedicated his life to serving people with much higher status than him, but who has rarely looked back at his life with any regrets, this is a profoundly moving film that invites one back for additional viewings quite regularly, daring us to journey into this world once again to find more details embedded with Ishiguro’s beautiful words, and James Ivory’s masterful adaptation of one of the finest works of literature in the English language.

What has always been most bewildering about Merchant-Ivory, who are almost definitively the most notable artists behind period dramas, is that their films tend to leap into the past and be bold adaptations of cherished literary works, but rather than being stuffy, turgid historical dramas, they are instead electrifying, poignant works that touch on some very human issues, some of them evolving from the page to the screen in absolutely gorgeous ways, as a result of the magical touch of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala put on them through her screenplays, and James Ivory’s ability to bring them to life vividly and with a potency that extends far beyond simply being verbose language delivered in cavernous chambers by actors with refined English accents. There’s a reason these films are so beloved, even if they could be considered dated – from the conceptual stage to the final product, there is a sense of sincerity going into every frame of the film, a profoundly compelling energy that comes from artists who understand exactly what they’re doing, after years of working tirelessly to bring these stories to life, paying tribute to the original literary works (constantly refusing to make the claim that they’re better than the original novels), while still going about exploring these ideas in their own distinct ways, inserting their own authorial voice without taking over the source material, which is often a problem with lesser forays into the realm of literary adaptations. The film avoids all the associated pratfalls, and becomes a masterful exploration of some profoundly human themes, filtered through the lens of a period setting that comes across as neither stiff nor restrictive, and rather than being a dull, dour affair, The Remains of the Day is an exhilarating, intoxicating drama that takes us on a profoundly interesting journey into a few precise moments in history, and gives us fascinating insights into life in post-war Britain, told through a poetic, stirring drama that has far more resonance than the countless films that it is often inaccurately compared to quite regularly.

According to Ishiguro, the impetus for The Remains of the Day came from an almost universal idea of the grand English manner and its constituents, which became a very distinct concept that has persisted for nearly as long as literature has existed. His aim was to take on this image and look at it from an entirely different perspective – and this immediately positions The Remains of the Day as a work that has some considerable variances from the stiff, lifeless period drama we’ve grown accustomed to. In both the novel and this adaptation, we see artists attempting to penetrate the veneer of sophistication, venturing beyond the superficial grandiosity of these estates, and instead looking squarely at the people who occupy it, particularly those that don’t normally find themselves the focus of such stories. It is an undeniably postcolonial concept for literature to focus more on the servants than the aristocrats, as it relates directly to the concept of the empire, which is now “writing back” to the former socio-cultural systems that built up these specific dynamics between the upper-class and those who they employ, and the butler trope in particular has a lot of merit, since they tend to be observers, individuals who are present in every moment of their masters’ lives, but are barely noticeable, and can thus glean an abundance of information without actually being considered as equal to those they’re extracting it from. This all sets the stage for a truly compelling drama, which Ivory develops into a beautiful story of individuality shown through the lens of two decades in the life of a manor, and the various people that weave their way through its hallowed halls, all tied together through the experiences of one man who was present to see all of it. This is a film that touches on many profound themes, and ventures far beyond the confines of simply the “upstairs-downstairs” drama that we have since come to expect from such material, embracing something far more complex and endearing.

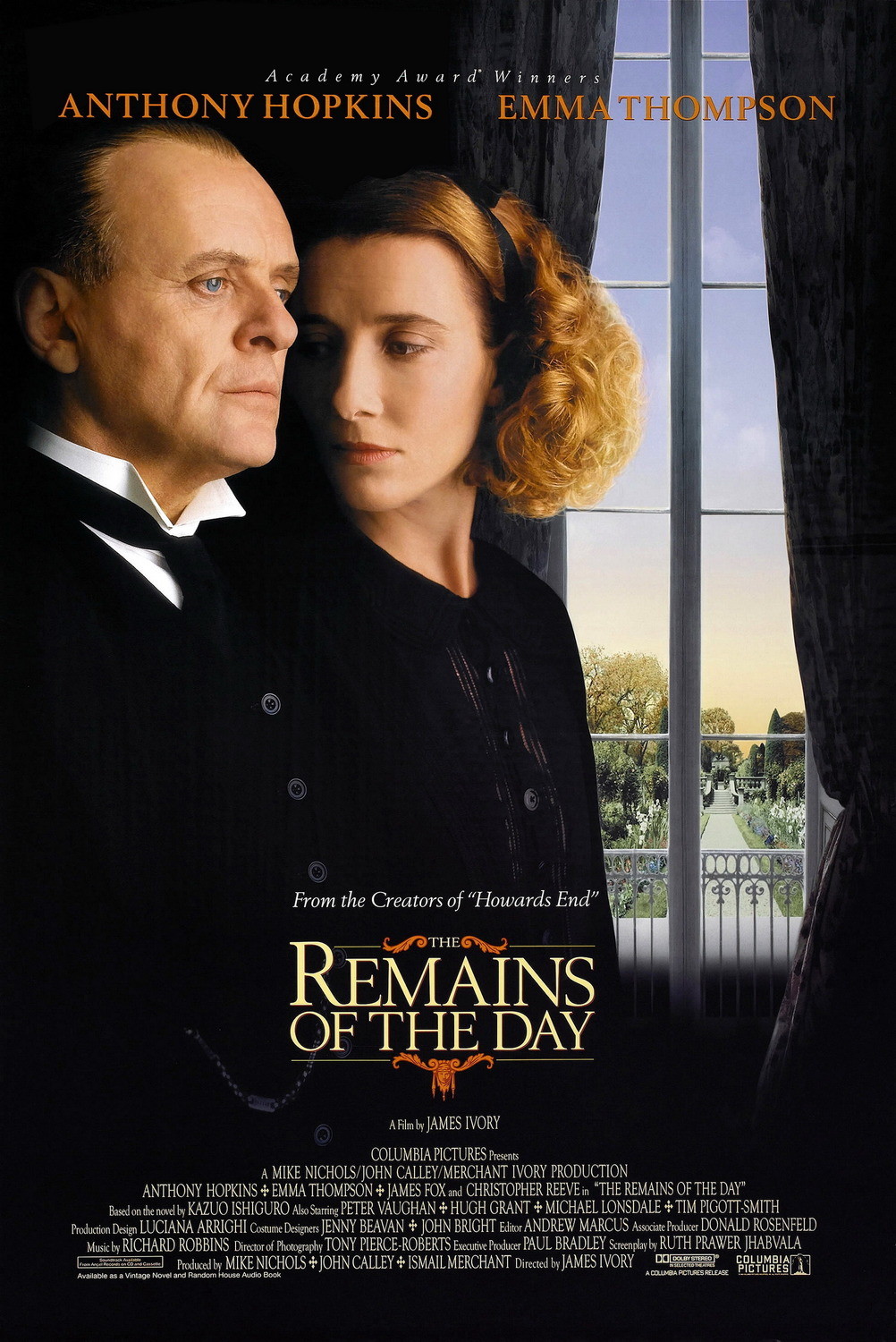

A discussion about a literary adaptation is inherently difficult, especially when both texts are equally as beloved, and the film version doesn’t deviate too far from the original. Ishiguro’s novel is a beautifully written piece, but the Merchant-Ivory version is just as compelling, and it takes the opportunity to develop on many of the aspects that a book is unable to. Mostly, this comes in how Ivory visualizes the narrative and brings life to the story, which can be traced back to the casting of the film. The Remains of the Day is a film with a large ensemble, but rather than just being one filled with recognizable faces (both for the time, and in terms of those who would reach their fame after this film’s release, such as Hugh Grant and Lena Headey), it’s exceptionally well-cast with actors who could play these roles convincingly, rather than just relaying the beautiful dialogue. The Remains of the Day serves as the film that many consider to feature Anthony Hopkins’ peak as an actor, his finest performance that may not be as widely seen as his iconic work in The Silence of the Lambs, but sees the esteemed actor giving some of his most nuanced, layered work. The role of Stevens is not an easy one, since it requires someone who could play a mostly internal character without coming across as passive. There are very few actors that could play such prickly tenderness, and through harnessing the very precise quirks that make him such a noted actor, Hopkins manages to develop Stevens into a profoundly interesting character that leads the film with aplomb. It’s one of the finest performances of its era, and could be the definitive portrayal of such a character. Dame Emma Thompson is equally as remarkable as Miss Kenton, the feisty housekeeper who goes toe-to-toe with Stevens and challenges him, bringing him back down from his feelings of superiority, and reminding him that we are all human, regardless of the responsibilities bestowed on us by some brutal cultural hierarchy that dictates social roles.

The Remains of the Day is a profoundly historical film, but not necessarily one that cares too much about specific events in the past more than it does the impact of them on the people who experienced them firsthand. A large portion of the film’s narrative centres on preparations for a major conference, whereby the master of the house will invite a bevvy of foreign dignitaries into his home to discuss the way forward with the simmering tensions that would eventually become the Second World War. However, the story isn’t too concerned with these specific machinations, being far more interested in exploring how those outside these discussions – namely the servants who were present for the conversations but not involved in it – grew to develop an aloofness to the outside world. For the character of Steven, his job requires him to be entirely objective, to the point that Darlington Hall is his entire home. It is only in the later parts of the narrative, set in 1958, where we see him actually venture out of the estate and into the rest of the world, which has some of the most profound commentary on the toll a life of service takes, since he is no longer in charge, and can’t control everything he comes across, which is conveyed beautifully in Hopkins’ vulnerable performance, as well as in his many scenes where he clashes with Thompson’s more world-weary Miss Kenton, who hasn’t quite surrendered to such objectivity yet. Filtering some very serious discussions on real-world issues through the perspective of someone whose entire career requires him to stay as distant from these affairs as possible, gives fascinating insights, and leads to some of the most poignant moments in the film, such as when Stevens is being interrogated by some of his employer’s colleagues, who ask him an array of difficult questions, to which Stevens probably knows the answers, but refuses to abandon decorum by giving proper responses, remaining loyal until the very end, in dedicated service to his master, rather than someone wishing to express their individuality.

These aspects of the story interweave with the very personal moments, since The Remains of the Day doesn’t hesitate to give us glimpses into Stevens’ life as a butler – Hopkins, who did research for the role by spending time interviewing certain individuals who had worked in the profession for many years, took inspiration from a longtime servant to Queen Elizabeth, who told him that when a butler is in a room, “it should be even more empty”. In contrasting this aspect of the story with the very internal struggle faced by the character, who has chosen a career that has stripped him of all his identity, to the point where even his leisure time is spent sharpening his command of the English language, so he may be able to do his work even more effectively, the film gradually builds to a haunting crescendo, where a sense of melancholy yearning envelopes the film, creating a sensation of despair on the part of the viewer, who can’t help but feel sympathy for someone who has dedicated every waking moment to servitude. The Remains of the Day weaves this side of the narrative with some profound commentary on memory, since this is essentially a film about the past, both in terms of the main character reflecting on his life at Darlington Hall, as well as a snapshot of a particular time and place in history, capturing the mentalities that dominated at the time, and unveiling certain concepts that now appear archaic, but were revolutionary at the time. Ishiguro wrote a masterful elegy to the past, the film pays incredible tribute to the men and women who committed themselves entirely to serving those who may have not always been appreciative of what a told it takes on the individual – and when you have only your memories to look back on, you tend to hold onto them more fervently, in fears of losing the few fragments of individuality one still carries with them.

Despite being an exceptionally well-made film with some tremendous performances, The Remains of the Day functions as more of a tenderhearted narrative odyssey into the trials and tribulations of the proverbial “invisibles”, the men and women hired to keep a household running, forming a small army on which the high-society and their cohorts are unknowingly entirely dependent. It’s a strikingly beautiful film that finds poetry in the banality, gradually revealing a new side to a common set of ideas that are often disregarded in works that look at those at the top, rather than the people who help maintain their lifestyle and keep their lavish lives running. Ivory was a master of tone and intention, and through working with two of his finest regularly collaborators in Ismail Merchant and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (who collectively formed one of the most significant artistic partnerships, since their work reflected a keen understanding of any of the many periods and milieux in which they worked), and The Remains of the Day is one of their most cherished productions, a heartfelt, sweeping historical odyssey that both manages to by sumptuous and gorgeous on a visual level, but also had a very profound human element, which came through by way of their development of the characters as more than just thin archetypes, but rather fully-formed individuals with their own depth and personal histories. The nuance conveyed in every frame of this film, and the ability to extract the most poignant emotion from situations that would otherwise not be all that notable is exactly the reason why this has become such a cherished film, and one that never fails to leave new viewers in awe, and bring previous ones back to once again witness the grandeur of profoundly moving story of individuality and memory.

Wow. This is a masterful piece of film analysis. Here we are provided a thoughtful reflection on the depth and breadth of artistic achievement that enhances our appreciation of the James Ivory film and enriches our knowledge of the art form.