The Pre-Code era was a time when Hollywood genuinely believed that you could make a film about a police officer going undercover to investigate an illegal drug ring by putting a moustache and hat on him and convincing everyone around him that he is a different person. Yet, this kind of flawed logic is more of a merit to this era of the Golden Age of filmmaking, where many directors took a few risks in bringing their stories to the screen in the years before the Hayes Code regulated what they could show on screen. John Francis Dillon did some prominent work during this time, rising to the status of a relatively solid journeyman director, directing over a hundred films from the beginning of the silent era, to the peak of the Golden Age – and in Behind the Mask, his adaptation of the short story “In the Secret Service” by Jo Swerling, he took an undeniably fascinating approach to the material, blending together genres and conventions in a way that seems revolutionary for this era of filmmaking, where everything was kept more or less within the confines of a particular category. The Pre-Code era was an experimental period, and while Behind the Mask is far from a flawless film (some of it coming across as absolutely ludicrous), it is nonetheless a thrilling and captivating drama with hints of many different genres woven into the fabric of a story that seems so ahead of its time, it’s bewildering to imagine how this was made almost a century ago, when such conversations weren’t only rare and somewhat unprecedented for a film made in 1932, but almost taboo entirely.

Behind the Mask exists at the perfect intersection between romantic drama, psychological horror and film noir – and Dillon, for all his effort, manages to effectively work in each one of these genres in a way that feels like he is actually getting somewhere, rather than needlessly blending every trope that was popular with audiences at the time. This is a constructive and meaningful use of conventions, and while it may be too ambitious for its paltry 68 minute running time (which is otherwise absolutely perfect for this story, being long enough to have enough time to develop its story, but departing just before it overstays its welcome), it works out when we look beyond the more traditional elements. This is a profoundly experimental work, which makes sense considering the sub-plot centering on a character who is only a few short beats away from being a mad scientist, and Dillon is working from a place of what appears to be genuine curiosity for all sides of the narrative – the intricate, quietly sinister moments of horror and the sweep sequences of dashing heroism exist in tandem, operating side-by-side in the creation of this deranged but effective thriller that covers material that was still somewhat unheard of in Hollywood at the time, which only adds to the impact of the story, since it could’ve been so much easier to have changed the details to something more palatable to viewers.

However, its insistence on courting controversy and delivering something cutting-edge makes Behind the Mask even more effective as a work that dares to be different. We were still a few years away from Reefer Madness and the hysteria that film incited in the global film-going audience, so for a film to be as frank and open about the drug trade as this, where it shows characters crossing some of the most sacred cultural boundaries to peddle narcotics, seems like it is ahead of its time, even if this wasn’t the first instance of drugs serving as the centrepiece for a film such as this. Dillon is absolutely intrepid in developing a version of this story where everything leads to some shocking revelations – there is enough simmering beneath the surface to justify this film going any direction (and there are so many potential subplots that we think will factor into the general narrative, only to realize they were nothing but non-sequiturs) – so the calibration to go towards what is more applicable culturally, rather than acceptable socially, was an interesting choice, and one that worked in developing the gritty, challenging nature of the film. In no way glamorizing the use of drugs, but rather using the hysteria surrounding it as the means to set off a series of incredibly disconcerting events that expose a darker side of humanity, Dillons manages to captivate the viewer and leave us oddly riveted, not something that can be expected from a film as seemingly-muddled and convoluted as this one.

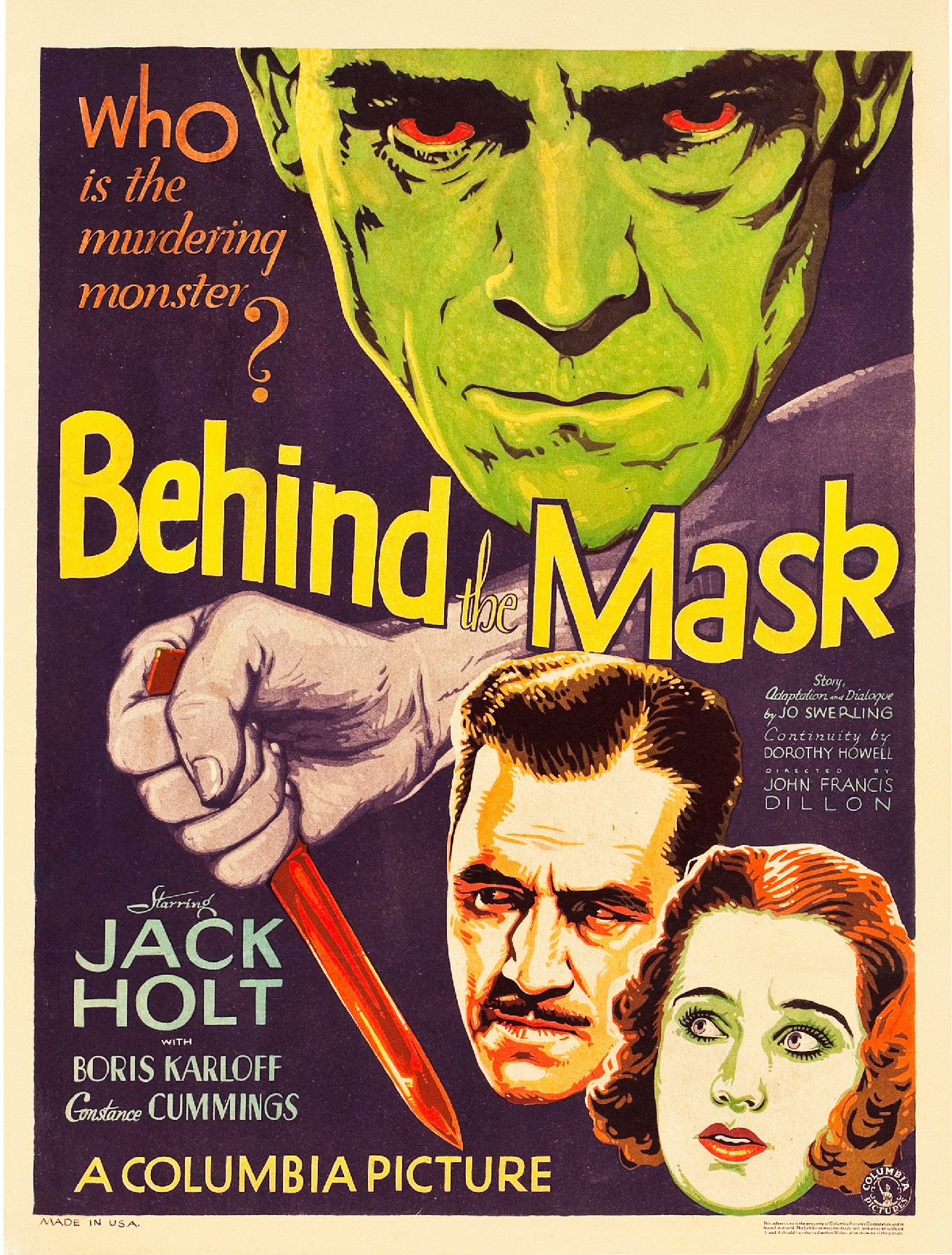

Blending genres can be truly effective when done well, and in the case of Behind the Mask, every choice seems deliberate and worthwhile. The presence of some of these actors also hints at Dillon trying to bring a certain level of prestige (Boris Karloff and Edward Van Sloan have two prominent supporting roles that steal every scene of the film), as well as conveying a sense of familiarity – how else do we justify someone like Karloff (playing a character who terrifies us through his words rather than his imposing physicality and disconcerting expressivity) or Van Sloan making such compelling villains, without actually doing what they were most known for. An actor playing against type is always interesting, but it’s even more effective when it comes at a time when people were cast according to very strict archetypes. Even for a film occurring in a genre not known for its character development, Behind the Mask gives us recognizable actors doing very strong work, all of which contributes to the varied complexities of a film that didn’t necessarily sell itself as something as compelling as this. Going into this film, we’d expect a solid but otherwise conventional crime drama with overtures of horror – but very few could’ve anticipated something as layered as this – and the scenes between Karloff and Van Sloan are absolutely terrifying, and the film should’ve probably given them more to do, rather than shifting to the wildly uninteresting Jack Holt and Constance Cummings, who are serviceable, but far from particularly effective. Yet, it all makes sense by the end of the film, especially after a particularly thrilling climax.

Behind the Mask is a fascinating work, and one that has been oddly neglected from conversations about the films that defined this era. It may not be particularly polished or void of shortcomings in the way that the more notable films from this era may have been, but what it lacks in refinement it makes up for in unhinged ambition. Helmed by a filmmaker audacious enough to dip into a variety of genres, and skilled enough to handle such an approach, the film is in safe hands, with Dillon delivering a tremendously satisfying psychological thriller that unknowingly set a foundation for a few different genres decades before they’d reach their peak. Intelligent, wonderfully written and populated by some very gifted performers who turned in work that met all the criteria for the assignment, Behind the Mask is an enthralling work of Pre-Code filmmaking that stands as one of the best examples of a director making use of this laissez-faire approach to storytelling to actually make a difference, showing a side of society that would have been heavily censored (and perhaps even entirely elided) in later years. Fearless but in a way that feels very organized and worthwhile, Dillon’s film is a masterful example of taking a few risks and watching them all work out in the favour of the larger production, which becomes one of the more complex forays into this subject matter that came from this otherwise tumultuous era in Hollywood history.