Towards the end of Hamsun, the ambitious biographical drama of Knut Hamsun, an iconic Norwegian writer and early proponent of Adolf Hitler’s ideologies, a doctor remarks that he is looking forward to encountering “the anatomy of a poet”, through his continued observations of the titular character as part of state-mandated proceedings in the effort to convict this once-great writer to harsh punishments after his beliefs went against the principles of the nation and its people. In many ways, this is exactly what Jan Troell was aiming to accomplish with this film, stripping away the layers of one of Norway’s most polarizing figures, a man who was both an incredible artist and a fiercely despicable human being, both of which warrant the intricate investigation of his policies, as made abundantly evident here. Troell has always been a loyal advocate for capturing the Scandinavian experience, and while both he and his iconic leading actor are venturing slightly out of their native country to tell a different story, their collaboration breeds an absolutely stunning drama that is biting, heartbreaking and woven together with the dedication of a pair of artists with a clear authorial vision, and the ability to bring life to even the most controversial stories. Beautifully-made, and entirely unforgettable, Hamsun is an essential work of biographical storytelling that removes all semblance of heavy-handed commentary, and instead becomes a strikingly straightforward account of the trials and tribulations of a man whose story deserved to be told, regardless of the angle it took.

The success underpinning Hamsun comes from the fact that it refuses to be a stuffy, melodramatic biographical account of its subject’s life, but it also doesn’t necessarily aim to be revolutionary either, since it understands that venturing too far out of one’s comfort zone can be as much of an obstacle as it is an achievement. Presented in the way that many of the greatest European period dramas of the century were, Hamsun sees Troell crafting a film along similar lines to those produced by Luchino Visconti and his artistic progeny, where it wasn’t so much a matter of telling a specific story and relaying the most accurate details, but rather capturing the spirit of a particular time and place, using the life of a notable figure as the guiding force for a striking exploration of some familiar themes. It stands to reason that Hamsun was the perfect muse for this story – he was someone who existed at the turn of the twentieth century, and saw a world rapidly changing, with his professional life extending all the way to the years following the Second World War, a period in which he may not have been as prolific a writer as he was before, but still carried many unique opinions on the direction Europe was heading, which forms the basis for this film, and gives Troell the chance to investigate this period without making a film that purports to be the definitive account of any of these concepts, but rather a fascinating character study of a legendary figure whose reputation was irrevocably tarnished by his beliefs and activities during this period.

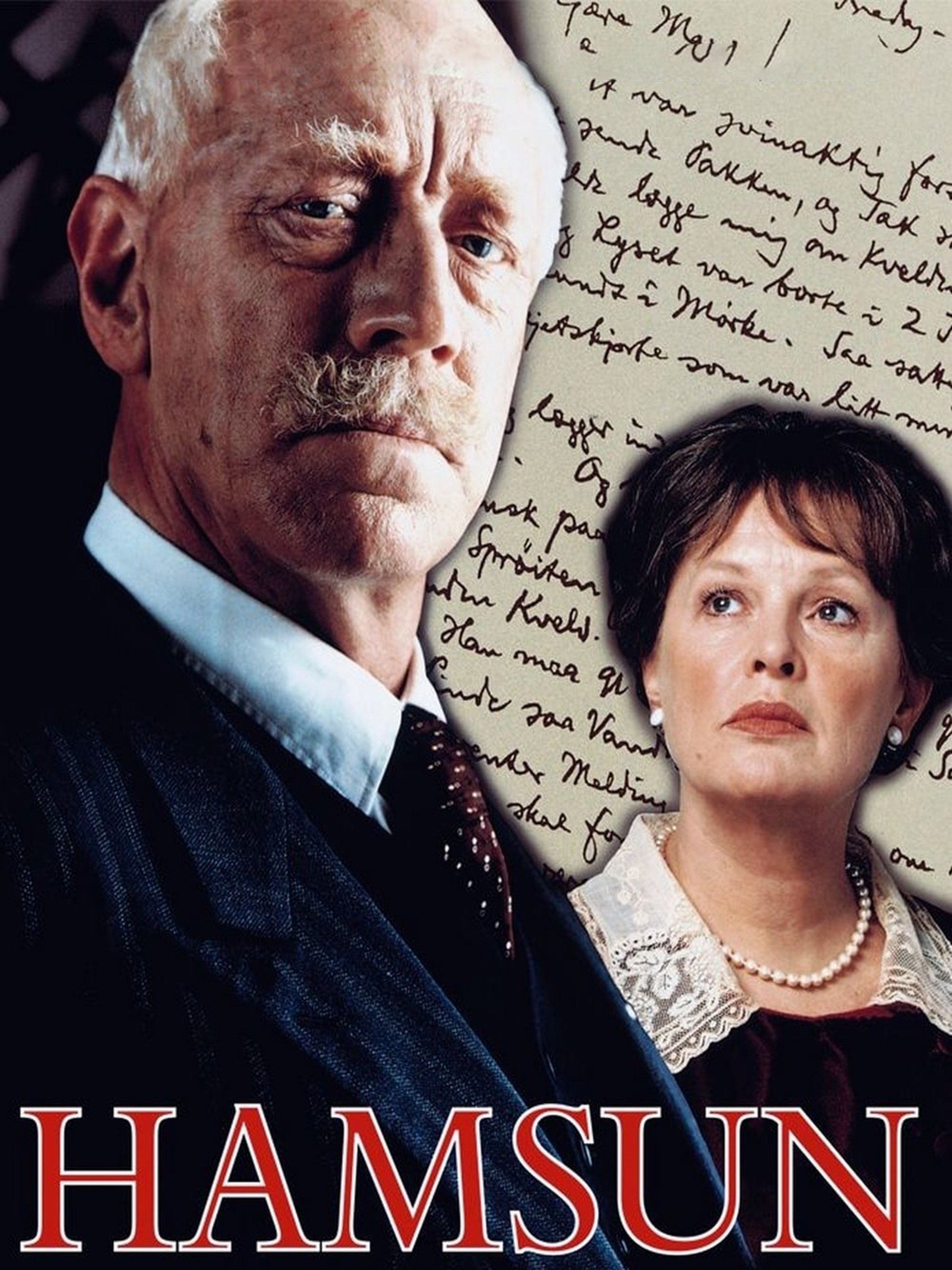

Max von Sydow delivers one of his greatest screen performances in the part of Hamsun, and collaborates closely with Troell (with whom he did some of his finest work, in particular The Emigrant and The New Land, both of which were similarly themed investigations of the European way of life, in conflict with other social systems with which it isn’t quite compatible), in the creation of a version of Hamsun that functions as an active participant in his own story, rather than just a passive effigy through which the director could assert his own interpretation of his tumultuous life. One of von Sydow’s most notable gifts as an actor was his ability to balance his incredible talents as a performer with his brooding physicality, and a distinct expressivity that allows him to convey any message without uttering a single word. In all stages of his career, von Sydow worked with directors who could effortlessly harness both qualities, employing them beautifully into the fabric of their films. However, it’s the work he does in Hamsun that feels slightly different. Known for being adept at playing both heroes and villains (being one of the very few actors who has played both Jesus Christ and Satan), this film presented him with a few new challenges in playing a man who was certainly on the wrong side of history, and held some abhorrent views, but wasn’t necessarily a bad person himself, but rather someone who was careless enough to not realize the gravity of his actions. Never one to back down to a challenge, von Sydow turns in a masterful performance that is positively brimming with life, each moment he is on screen feeling like a revelatory moment in the career of an actor who managed to do something unique with every role, this one not being an exception.

Hamsun navigates some challenging narrative territory, especially in how it takes on the development of the titular character. The obstacle here was to neither portray Hamsun as some maniacal villain, nor show him as some misunderstood intellectual with some bad ideas. The reality was that he was likely a combination of both, a great artist but a despicable person, which the film is certainly not against demonstrating regularly and with incredible sincerity. Finding the humanity in someone whose only other worldwide claim to fame (other than being an early recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature), was that he was a well-known sympathizer of Adolf Hitler and Nazism, in a time when his country was vehemently against the ideologies, and actively fought against the encroaching influence of the “new Europe” that they were apparently promised. It’s difficult to take on such a complex plot and not resort to over-analysing every aspect of the socio-cultural milieu – and as a filmmaker with a keen understanding of what works on screen when it comes to telling the story of Europe, Troell stands head and shoulders above his contemporaries, at least in terms of extracting the emotion from a story and repurposing it as an effective propellant for the narrative. Hamsun is a film about memory, but rather than being a nostalgic deconstruction of a writer’s past, it is an active glimpse into his origins, and the path he chose to take, which led him to the particular moment we encounter him. Every moment comes across as authentic and impactful, and Troell’s grasp on the material is strong enough, he is able to reconfigure an otherwise sprawling epic into a solid, tightly constructed biographical drama that tells its story without the aid of any of the hackneyed techniques normally used in the genre.

Hamsun is an incredibly multilayered film that takes its time to establish a clear tone, but once it hits a particular stride, very little can be done to dissuade us to think this is anything other than a fascinating portrait of one of Europe’s most interesting writers, whose life has been obscured by a cloud of poor judgements and inappropriate actions that make him something of a tragic figure, since he was someone driven by his emotions rather than logic. A wonderful companion piece to Maria Schrader’s Stefan Zweig: Farewell to Europe (another film that tells the story of Europe during the rise of Nazism through the perspective of a world-renowned writer who holds very particular views about the rising ideologies), and a generally strong effort from a director whose interest in the subject matter makes for a truly captivating story of coming to understand oneself through exposure to conflicting ideas. For Hamsun, he had to choose between loyalty to the country that nurtured him and gave him the artistic freedom he needed to express himself, and his own curiosities about a political system that benefitted people like him. Hamsun is a tremendous film that covers the subject’s life in a way that affords him the dignity he deserves, but doesn’t justify his choices, instead presenting them objectively and with a sincerity that means so much more when it becomes clear the depths to which the film is willing to head for the sake of telling this story authentically and without even the slightest trace of sensationalism.