Satyajit Ray changed cinema, an undeniable fact that has its basis in his ability to represent life in a way that very few other artists were ever able to. A creative soul that never avoided taking on a few challenges with his work, he was perpetually venturing into the realm of the unknown, pioneering an entirely new movement almost single-handedly, bringing a new kind of filmmaking to his come country that would go on to have perhaps the most significant influence on how Indian cinema has functioned since then. Caught between the neo-realists of post-war Italy, and the bare-boned anger of kitchen-sink realism that took over Great Britain in the coming decades, Ray’s work was reflective of many different ideas, portraying life as purely and with as little furnishing as possible. Even by modern standards, the simplicity of his work is astonishing, with his ability to extract an endless amount of emotion through the most sparse and unassuming situations being unprecedented. Perhaps the work that is most definitive of his career is his three-part masterpiece, The Apu Trilogy – and even just looking at the first entry into that series, we can easily understand why it would propel Ray to the status of being one of the true masters of cinema. Pather Panchali (পথের পাঁচালী, “Song of the Little Road”) is quite simply one of the finest films of its era, and the one that was the beginning of an incredible, industry-changing trilogy, but started the career of one of cinema’s great stalwarts, setting off a chain-reaction of artistic works that are defined by their dedication to representing reality, telling the stories of real people going through life and facing all obstacles, and most importantly, commenting on the smallest idiosyncrasies of our shared existence. The fact that Pather Panchali was Ray’s very first film (and in part inspired by one of his artistic heroes, the incredible Jean Renoir, who compelled Ray to make this film) only proves the value of pursuing one’s ambitions, because it can sometimes result in history being made.

Normally, the prospect of writing about an unimpeachable classic of cinema is daunting to say the least – not only is there a need to give your own thoughts and insights, but you also need to say something that adds to the conversation, rather than just stating objectively the reasons why it has amassed such a following. As perhaps the consensus choice for the greatest Indian film of all time (at least from an international standpoint, since it is very likely that we’ve only scratched the surface of Indian cinema, which is sorely represented outside of its native country), there is a lot of pressure on Pather Panchali when it comes to describing what it means to both Ray’s career, and film history in general. Yet, watching this film is such a transcendent experience, it’s nearly impossible to resort to the same overly-analytical discussions that normally infiltrate even the most impassioned manifestos on some of the most notable entries into the canon of great works. Pather Panchali is just such a beautifully simple film, composed with elegance and insights that prove how Ray hit the ground running and established himself as a truly essential voice right from the outset. The story of a young Indian boy growing up in rural Bengal at the beginning of the twentieth-century is sufficiently to pique the interest of potential viewers, but also simple enough to tell us exactly what to expect. Yet, nothing can prepare us for the wealth of emotions that the director is about to unleash on us, and regardless of how conditioned we may be to the kind of stories he tells, there is an element of surprise that still persists throughout this film, even on repeat viewings – and through the sheer willpower of being able to come up with an original idea, and execute it with precision, earnestness and an abundance of heart, Ray crafted quite simply one of the finest films of all time, and one that has yet to show even the slightest sign of ageing, both visually and in terms of its narrative.

From a modern standpoint, in a world that has seen social realism go to impossible lengths, Pather Panchali shouldn’t be as impressive as it is – yet, it somehow manages to exceed all expectations and be just as refreshingly bold today as it was nearly seven decades ago when Ray unleashed it into the culture. When it comes to realism, the most important tenet in terms of any film that takes such an approach, is that the best kind of film is the one that makes you forget that you’re watching one. The director submerges us in this world, with everything from the biggest cultural detail to the most intimate character-driven quirk being entirely authentic, and based in something very close to reality, at least in terms of what Ray was doing with the material. We become a part of this world, and despite it being set in a time and culture many of us have no first-hand experience of, we feel as if we are alongside these characters, seeing their lives unfold before our eyes. It’s not an easy task, especially when you’re working within the confines of something so deeply rooted in traditions – but something that has always been quite striking about Ray as a filmmaker across his entire career is, despite being an artist profoundly intent on exploring the various intricacies of his nation’s many cultures, he made these stories accessible. The cultural references and small details are woven so neatly into the narratives, supporting the universal stories that we can all relate to, and enriching our knowledge of what is being portrayed on screen, rather than putting us in a position where we’re confounded by the specific nuances needed to understand what is transpiring. Perhaps it is his understanding that film is a medium that needs to speak to a wider audience, or simply his undying devotion to celebrating his background, but Ray’s constant ability to make even the most banal details so incredibly captivating is a strength that serves each and every one of his films exceptionally well, starting with Pather Panchali, which feels so genuine and heartfelt, it’s difficult to see it as anything but an overwhelming success.

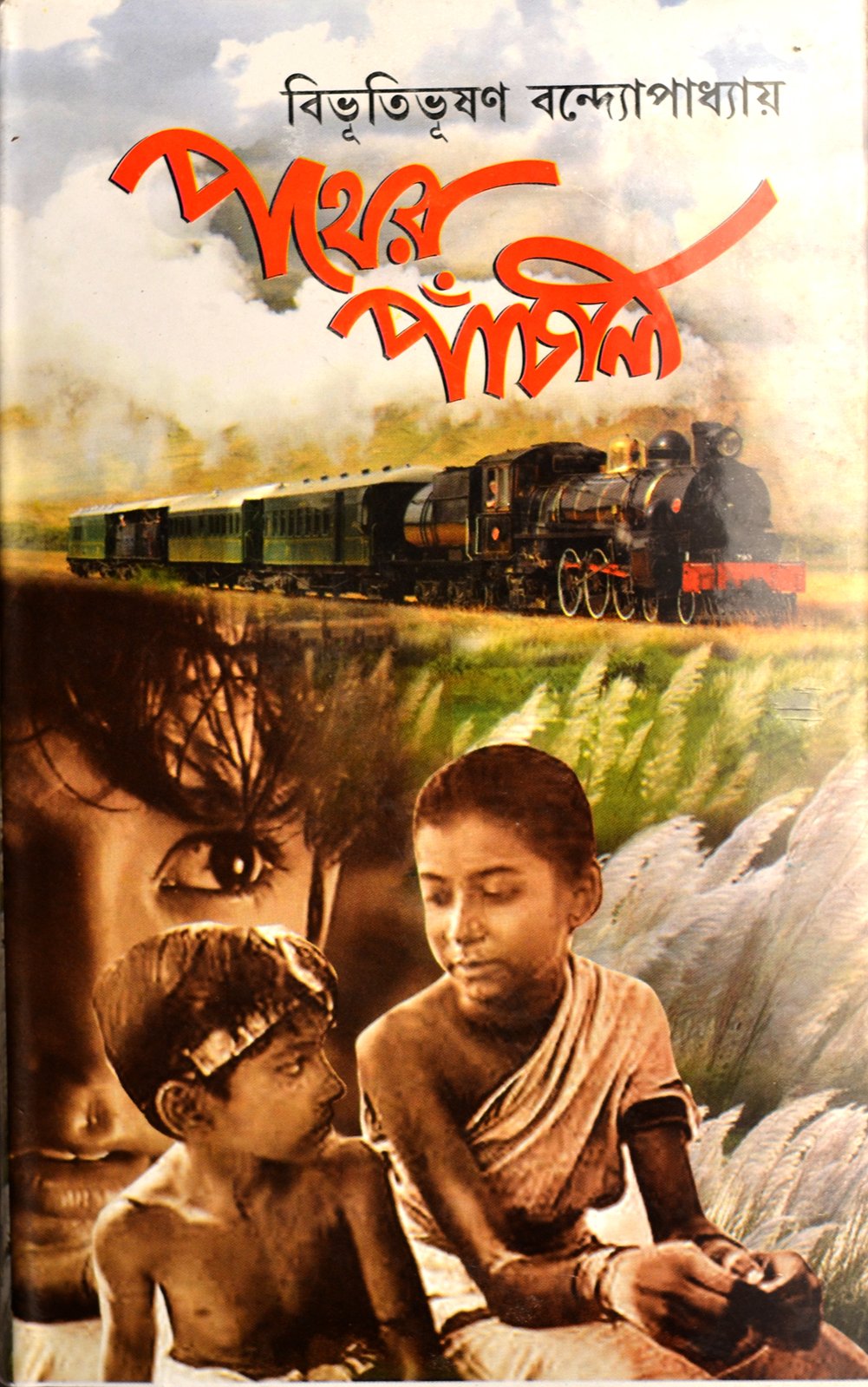

Ray’s success in telling this story doesn’t only reside in the tale he’s spinning, but also in the manner in which he does it. His methods are simple but effective, and have such a tenderness about them, we sometimes forget that what we’re watching is a fictional film (extracted from the eponymous novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, which is considered one of the most insightful works of Indian literature, much like this adaptation would go on to become). The director is bringing this story to a wider audience through the most heartfelt, meaningful filmmaking he could muster with the resources he had. The result is a very simple but thoroughly compelling drama that uses the intimacy of family better than most films I’ve seen. Tonally and in terms of the actual story, Pather Panchali is a marvel, cutting to the core of existence without even a hint of overwrought meandering or heavy-handed emotion. Everything we feel in this film comes from the director’s authentic balance of tone, with moments of gentle, heartfelt comedy being contrasted with broad strokes of tragedy, showing the volatility of life, and how the most joyful moment can immediately be followed by a harrowing event, or perhaps even the converse, where even the grimmest days are followed by a sunrise that brings a new dawn of hope (mercifully, Ray avoids such stating such cliches so explicitly, leaving it up to awe-inspired viewers such as myself to fill in the blanks). It’s a gorgeous striking work, and through working closely with the director of photography Subrata Mitra, Ray manages to capture the beauty hidden in this part of the world with such vivacity, bringing life to even the most inconsequential details. Several moments in Pather Panchali cause one to stop in their tracks and simply marvel at what is being done with the camera, and the ability to wrangle such pulchritude from such simple means will always be an astonishing feat, and one of several reasons why Ray is a filmmaker who deserves every iota of acclaim and success he garnered throughout his storied career.

Pather Panchali is an incredibly human story, provoking many of life’s most challenging questions for the sake of venturing deeper into the experiences of being alive. Midway through the film, the titular character’s mother is speaking about him and what purpose he brought to being born – and she questions whether “he was born to die, or was he born to survive?”. In a film as profound and meaningful as this, such a line would easily have gotten lost, but something about it lingers, especially since there is a clear message being conveyed here. Pather Panchali is not a happy film – there are moments of joy, and Ray knows how to extract the humour when he needs to, and for a specific intention – but this is a film about suffering. The entire trilogy is about a journey, and this is just the start of it. It begins on a melancholy key, and gradually declines into a harrowing account of a family going through hardships, their lives falling apart around them. The growth of Apu is contrasted with the decline of their house – and setting the film entirely within their home and the immediate surroundings was a fascinating decision, since it shows the attachment one can have to a particular place, especially one with a very personal history. The film oscillates between the idealistic Apu growing to see the literal cracks and flaws in his home (and by association, the metaphorical understanding that his upbringing was not as perfect as he imagined when he was too young to realize the inherent problems), and by the end, when we see a snake, a representation of rebirth and starting new in Indian culture, slithering into their home, it’s clear that every frame of this film carried an abundance of meaning that often takes several viewings to fully realize. It’s a fascinating allegory that is only one fraction of the symbolism Ray uses throughout the film, making sure that the idea of survival is vividly represented.

Over the next few days, I will be revisiting the other two films in the Apu Trilogy, so there is still quite a bit that needs to be said about Ray’s incomparable masterpiece, a collective of three powerful films that share a common character, but look at an array of different themes. The first entry is an absolutely stunning coming-of-age story that looks at the earliest years of childhood, focusing on the innocence that keeps us optimistic, long before we know of the true perils of the real world. Yet, beneath all the tragedy, Ray proves himself to be a profoundly idealistic director as well – even the stunning final shot, where the family ventures to an uncertain future, is portrayed as a blend of both harrowing despair and inherent optimism, since one of the few benefits of not knowing what the future holds is that we don’t have any expectations, and that it brings a new start. For a character like Apu, who has spent the first few years of his life in one place, this just represents another chapter in his journey, which the director would explore beautifully over the next two films. More than anything else, Pather Panchali is a film that celebrates life and finds joy in the smallest moments. It isn’t delusional enough to genuinely think that blind-hope is the key to a happy life, and that there is always a bright side to every situation. However, it also shows the value of not being weighed down by the sadness, since the future is a destination that has many obstacles, very few of them we can predict. Yet, through his compassion and profoundly humane approach to telling stories, and his masterful prowess behind a camera, Ray weaves a story that is deeply moving, hauntingly beautiful both narratively and visually, and told with an authenticity that reflects life and its many challenges with nuance and tender admiration for the lives of ordinary people, who inspired Ray to create such vivid patchworks of existence, sharing his nation’s culture through bare-boned, simple but incredibly affecting filmmaking that has yet to be matched in terms of how representative it is of reality.