No one was ever able to perfect the art of melodrama quite as well as Douglas Sirk, a director whose career is almost entirely defined by the range of intimate, profoundly moving dramas that combined familial strife with socially-charged commentary, forming complex tapestries of the human condition that were rarely anything but thoroughly riveting and moving, to the point where even the most cynical viewer would be swayed by their charms. One of his most significant works is Imitation of Life, an adaptation of the novel by Fannie Hurst (which was previously adapted into a film in the 1930s by John M. Stahl, one of the forerunners of the melodrama genre, and a clear influence on Sirk), which tells the story of two mothers and their daughters making their way through a bigoted, hostile world that is not kind to those who fall outside the confines of what is considered ordinary. A film that may feel somewhat dated in its ideas (although this is very much a remnant of the time in which it was made, since so much of this commentary relates to the issues of the day), but has an emotional resonance that can rival absolutely any contemporary film, Imitation of Life is a masterful excursion into the core of existence, delivered by a filmmaker whose ferocious attention to detail and willingness to plumb emotional depths to the point where it becomes almost harrowing in how it addresses certain themes, that many of his contemporaries refused to do, in fear of losing the sophistication that dominated such dramas at the time, made him an enigmatic artist who took a mirror and reflected our own existence right back at us, persistent in his endeavour to capture a side of life that is recognizable but severely under-represented, particularly in such frank and unflinching terms.

The 1950s had several watershed moments for racial representation in the world of entertainment, with a more conscious approach to portraying issues relating to the civil rights movement being prevalent, many artists sowing the seeds of defiance that would sprout in subsequent decades. In the years of its release, Imitation of Life was accompanied by a film that treads familiar territory, albeit from a more low-budget, intimate perspective – John Cassavetes’ Shadows, a film that often tends to be discussed in contrast with this film. Both centre on the intersections between race and social order, particularly taken from the perspective of families, where someone is undeniably black, while another is light-skinned enough to pass for white. Naturally, in both instances, the lighter-skinned characters were portrayed by white actors with features vaguely ambigious enough to convince audiences, granted they suspended disbelief. This is essentially where the comparison ends, especially since Imitation of Life is a superior film for a number of reasons – and occurs as the alternative to Cassavetes’ more groundbreaking, pioneering work of independent cinema. A more lavish excursion, but one that has just as much soul and heartfulness as the other, Sirk proves to be in his element with this film, crafting a tender, shattering story that takes the prevalent issue of racial inequality, and applies it to a much more intimate story of identity, focusing on a young woman ashamed of her heritage, to the point where she outright denies it and causes great despair in her mother, who would like to believe that she taught her daughter to be proud of who she is. It’s not an uncommon story, and it’s one that is still resonant to this day, despite this film being over sixty years old, and based on a novel that was first published nearly a century ago – and any work of literature that can be both a document of its time, and one that stands up as a timely piece in the contemporary world, is always going to be worth something.

Looking at this film, we can easily provoke this generally simple story into an insightful discussion on the role of identity in our daily lives. Sirk was a master of layered filmmaking – on the surface, these were lush Technicolor odysseys that are produced with the full-might of the Hollywood machine, using major stars and elaborate sets to create worlds within the confines of the studio sets. They’re sumptuous and stunning to behold – but this isn’t solely what keeps us enthralled, almost becoming supplementary to the more meaningful parts of the film, such as those that go almost entirely unsaid, coming about in the more quiet moments of character-driven narrative. Sirk flirts with a multitude of themes – ageing in the modern world (with the film centring mostly on two women on the other side of middle-age, leading very different lives that bring them joy, but only to an extent), the role women played in the decades succeeding the end of the Second World War, where they were no longer expected to be only complacent housewives (but before the second wave of feminism reached its peak, many of its roots being found in the fabric of this film) and, as we’ve mentioned already, race. Sirk was an intrepid filmmaker who never avoided having difficult discussions – and Imitation of Life is absolutely one of his most well-known films for its earnest approach to material that could’ve so easily been overwrought or unnecessarily convoluted, had he not chosen to keep everything at the fundamentally human level. His films are brimming with heartfelt emotion, very little of it coming across as anything other than entirely authentic – and this was one of many reasons why he is one of the defining figures in the melodrama genre, since his constant ability to capture not only the most intimately human moments, but also accompany them with impactful (but remarkably restrained) emotion, makes for truly captivating cinema that breaks boundaries without ever needing to resort to hysterics, despite the fact that so much of this could’ve legitimately warranted excess, which the director is vehemently against.

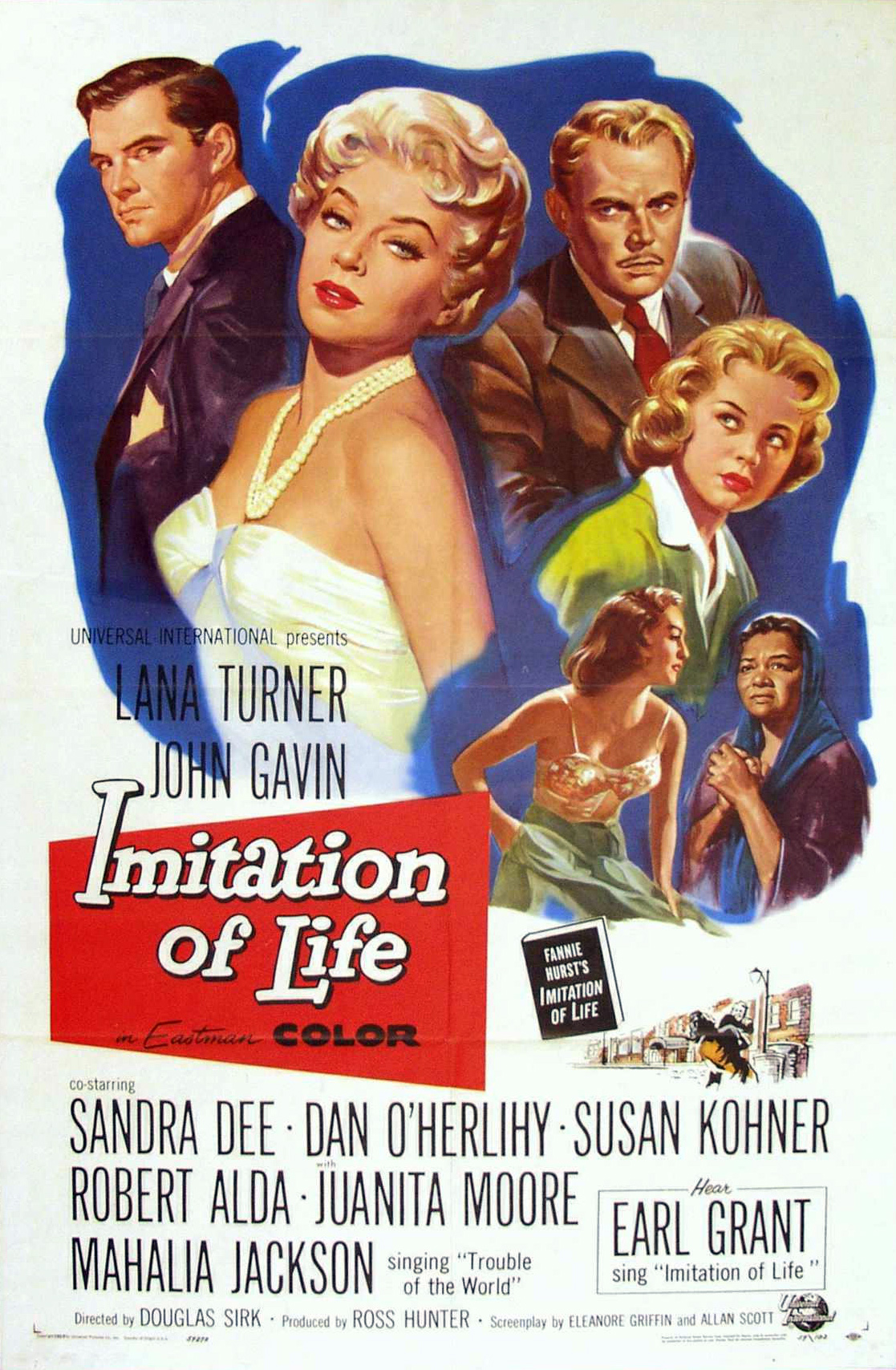

As is the case with the majority of films that are considered definitive entries into their particular genre, Imitation of Life is a difficult film to address, since it’s a true melodrama classic, and therefore often tends to be perceived as being the signalling post for every other film in the genre, which results in unnecessary expectations being put on it. What keeps this film from collapsing under this burden is the simplicity it is built on – it is flexible in nearly all of its themes that makes it so relevant, over half a century after its initial release. It feels refreshing and honest, and is quintessentially the work of a director who could capture the spirit of a particular time and place like very few of his contemporaries. The performances from the actresses in this film are exceptional – it may be built on the reputation of the iconic Lana Turner (who is absolutely exceptional), but it’s Juanita Moore that overshadows everyone, delivering a knockout portrayal of a woman whose warm, wide grin conceals a pain from a life being perceived as lesser, something she hopes her daughter will never have to endure. Moore is just sensational, being the performance in the film that truly establishes it as something special, elevating it every time she is on screen, and proving to be someone who could handle some very difficult material with nuance and aplomb. This isn’t to underestimate Turner, who successfully uses her almost ethereal glamour in a way that comments critically on her status as a wildly popular actress, allowing her to develop the character as a fascinating individual who goes toe-to-toe with the rest of the cast, and forms the emotional core of the film. Moore and Turner are complemented wonderfully in the later parts of the film by Sandra Dee and Susan Kohner, who may enter the film relatively late (playing the older versions of the protagonists’ daughters), but deliver very strong performances that work well in the context of the story. There’s a lot more to the spectacle in a film like Imitation of Life, which truly benefits from how it so clearly cherishes its characters and wants to portray them as fully-formed, complex individuals.

Imitation of Life is a terrific film – the emotions are authentic, the performances are astonishing, and the narrative is a decades-sweeping odyssey that features discussions on a range of powerful, poignant themes that are as relevant today as they were in 1959, where Sirk fought against conventions and told a story that carried so much more meaning than a wide-array of other “message films” were at the time. It’s a beautifully-constructed melodrama that never cheapens the impact of its message, but instead takes a path that allows for a riveting exploration of the human spirit, taken from the perspective of a filmmaker whose primary goal has always been to do just that, capturing the most intimate moments that often go under-represented in more populist fare. It’s not always the easiest film to watch, not only because Sirk is working with several different narrative threads, but also due to the fact that there’s always something lurking just out of sight, a challenging perspective that lends credence to alternative views on the world, showing disdain for the belief that what is conventional is automatically what should be accepted. Meaningful and brimming with a very unique energy that allows it to be both life-affirming and heartbreaking, Imitation of Life is an absolute triumph, a meditative exercise that is vehemently against settling for the bare minimum, and emerges victorious as a piece of cutting-edge social commentary cleverly disguised as a bold melodrama.