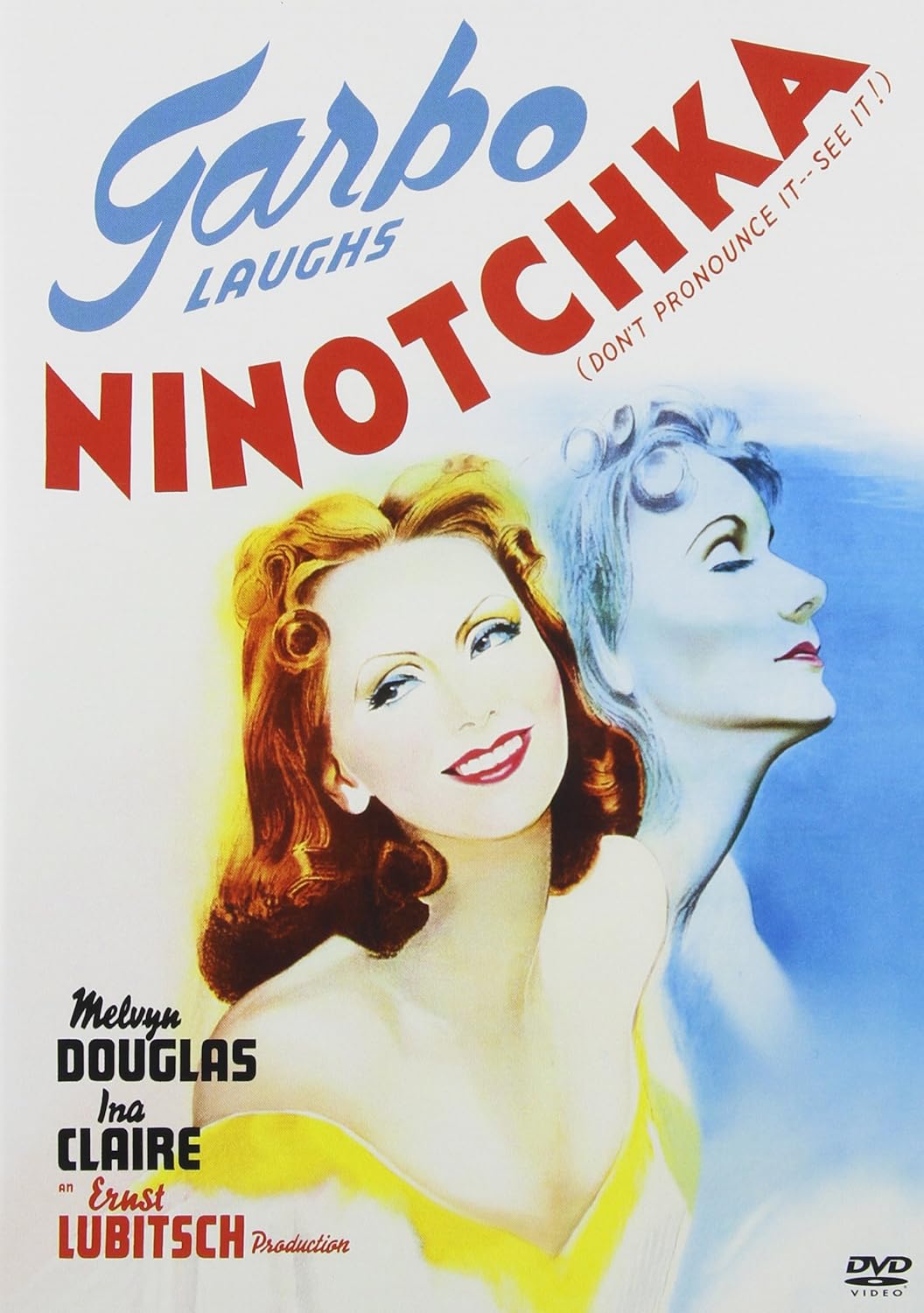

Upon its original release, audiences were presented with posters for Ernst Lubitsch’s iconic Ninotchka, on which the words “Garbo laughs!” were plastered. This should be familiar to anyone with a passing interest in this era of Hollywood history, and will likely evoke some strong reactions, depending on how one feels about the concept being portrayed. Obviously, it referred to the film’s star, Greta Garbo, who was at that point one of the industry’s most enigmatic stars – an actress of astronomical talents and an even more impressive relationship with the art of acting. Undeniably one of the screen’s most compelling presences, Garbo was the definition of a cinematic legend, and someone who found her way across the industry in a way that very few actresses have ever been able to do. With the exception of an early short film, Ninotchka was Garbo’s first comedy, a move to lighter fare that was quite a coup, considering how intensely she was adored for her dramatic material. It was also her penultimate performance, the beginning of her decision to step away from the limelight and retire from the profession in which she had excelled so well – audiences paid to see her, critics praised her wide-ranging talents, and the industry absolutely adored working with her. However, there is so much more to Ninotchka than just the stories written about it, or the reputation it has amassed over the past eight decades – watching it from a contemporary perspective proves what an absolute delight this film was, and how it stands as one of the most endearing comedies of its era. What tends to be a problem with Golden Age comedies is that many tend to be propelled almost solely on the force of nostalgia, which is far from the case here. This is an upbeat, outrageous romp that has as much charm as it does soulfulness, with the proverbial “Lubitsch Touch” being in full effect throughout. It is as refreshing and hilarious today as it was in 1939, which is quite an achievement, especially for something as quaint and unassuming as this.

Garbo was a performer that fit so well into the world of comedy, it’s surprising that she didn’t work in the genre more often – although one could claim that she was so enamoured with the experience, that she only chose to do comedies after this (to be fair, she only made one subsequent film). The role of Nina Ivanovna “Ninotchka” Yakushova, the stern Russian diplomat and well-regarded problem solver, was a perfect fit for an actress known for her stoicism and elegance. At first, she is a cold and aloof character – her sharp features and penetrating glance only served to heighten this. Then over the course of the film, her icy demeanour begins to thaw – she becomes more comfortable with her Parisian surroundings, more adept at being free of the strict constraints of the Soviet Union, and able to exercise her liberty in ways that she never had been able to before. Each moment of Ninotchka sees Garbo operating at the very peak of her talents – there isn’t a line reading or movement that isn’t brimming with the graceful sophistication that Garbo was known for – and when contrasted with her underlying comedic talents, which were far more complex than many of her dissenters would give credit for, there is something that can be said about her process of bringing this character to life. Garbo truly was one of the greatest actresses to ever wander through the medium, and even when doing something as lightweight as Ninotchka, she brought the same steadfast determination and willingness to venture towards emotional depths that more unskilled actresses at the time were too hesitant to do. She climbs to impossible heights, and charms every one of us along the way – and if we’re diligent, we’re able to accompany her on the journey, traversing some intimidating narrative territory and coming out of it entirely enthralled, and absolutely delighted in every possible way.

There is something quite enduring about certain comedies, whereby they have premises that could have just as easily lent themselves to a straight drama, but were instead taken from an entirely different perspective, and made to be comic gems that endeavoured to delight audiences and bring them joy. Lubitsch was consistently brilliant at this, finding heartfelt comedy in the most unexpected stories, and crafting some magnificent work through the reliably use of his distinct brand of humour. Ninotchka has a premise that had all the makings of a very serious romantic drama, with nothing being particularly funny about the story at the core of the film – a loveless woman ventures to a foreign country to accomplish a task set by her restrictive homeland, which relishes in squandering the freedom of its citizens. The best kind of comedy is often the one that is the most unexpected, arriving when no one anticipates it, and staying long after we’ve had our share of the joy embedded in the story. This is the aspect which immediately situates Ninotchka as an interesting example of Golden Age comedy, since its plot isn’t always the most buoyant or entertaining taken on a purely conceptual level, but rather traverses more serious narrative territory, bringing out the unique humour that isn’t obvious at a cursory glance, but becomes evident the further we venture inwards. Through his earnest approach to the material, and his ability to derive a great deal of comedic bandwidth from what is essentially a very simple story of cultural collision, Lubitsch made an immediate classic, a film that never abates in its desire to be an upbeat, joyful affair that leaves the dour, stern themes behind in favour of a more universally-resonant story that can make anyone laugh at even the grimmest prospects that tend to underpin this film – and the added inclusion of some triumphant romance only sweetens the experience and makes it such an absolute delight.

Lubitsch was undeniably a powerful artistic force for cinematic comedy – his work bridged the gap between the silent era, where slapstick dominated, and the era of screwball comedies, where it was more focused on developing characters and creating situations where audiences could find their own lives and experiences reflected to some degree. Ninotchka is a film insistent on singing a gleeful refrain that celebrates life and its small idiosyncrasies, with Lubitsch managing to once again extract such poignant humour from the most simple spaces. There’s no need for broad strokes or laborious effort – it’s perfectly adequate to have an entire scene set in a restaurant, where the only intentions was to demonstrate how dour the titular character is by having her romantic interest (a staggering Melvyn Douglas, who is rarely given the praise he deserves for acting across from Garbo, and still managing to leave an impression) try and fail to amuse her through his hackneyed joke. There’s a certain respectability that comes from a film that doesn’t feel compelled to put in an enormous amount of effort into giving the audience something to enjoy – the comedy unfolds organically, and Lubitsch’s instinctive understanding of what it is that makes us laugh is employed consistently. Added to the sweetly sentimental romance story that gradually becomes the focus of the film, Ninotchka succeeds splendidly, finding such a poignancy in the most unexpected recesses of the soul, which are exploited with a sophistication rarely glimpsed so clearly. The enchanting nature of the film, taken alongside the more heartfelt story of coming to terms with one’s own identity and surrendering to the desires of the heart, which are often in conflict with the logical thoughts that push us away from satiating our carnal cravings, make for such a thoroughly riveting work that has some real-world significance, even decades later, where it is just as fresh and endearing as it was before.

The Lubitsch touch isn’t something that should be taken for granted – very few directors could make something that feels so genuinely magical, but through the sheer force of his unique artistry, the director succeeds wholeheartedly, finding a spark that propels this entire work forward and makes it so utterly unforgettable. Garbo is doing so much with her time on screen, her ethereal grace interweaving with her fantastic comedic timing in the creation of an exceptionally exciting character that appears so much more authentic when in the hands of someone with as implicit an understanding of both the machinations of the high-society, and the more visceral aspects of one’s own unimpeachable humanity. It’s a delightful performance that may be relatively lightweight, but has a depth that could only be brought by someone with as deep an understanding of character as Garbo. Ninotchka is a truly exceptional work that gives us something so thoroughly enduring. Comedy doesn’t always age well, but when there is a work that hits all the right notes, and manages to be both timely and timeless (a nearly impossible construction, but which Lubitsch succeeded at regularly), it’s difficult to not be as enthralled by a film like Ninotchka. Upbeat, brimming with heart and soul, and executed with towering precision and an abundance of indelible moments, it’s not surprising that this has come to be seen as one of the defining comedies of its eras. Garbo may have laughed, but we did the same, all through the impeccable vision of a director who could command his craft like very few others ever could.