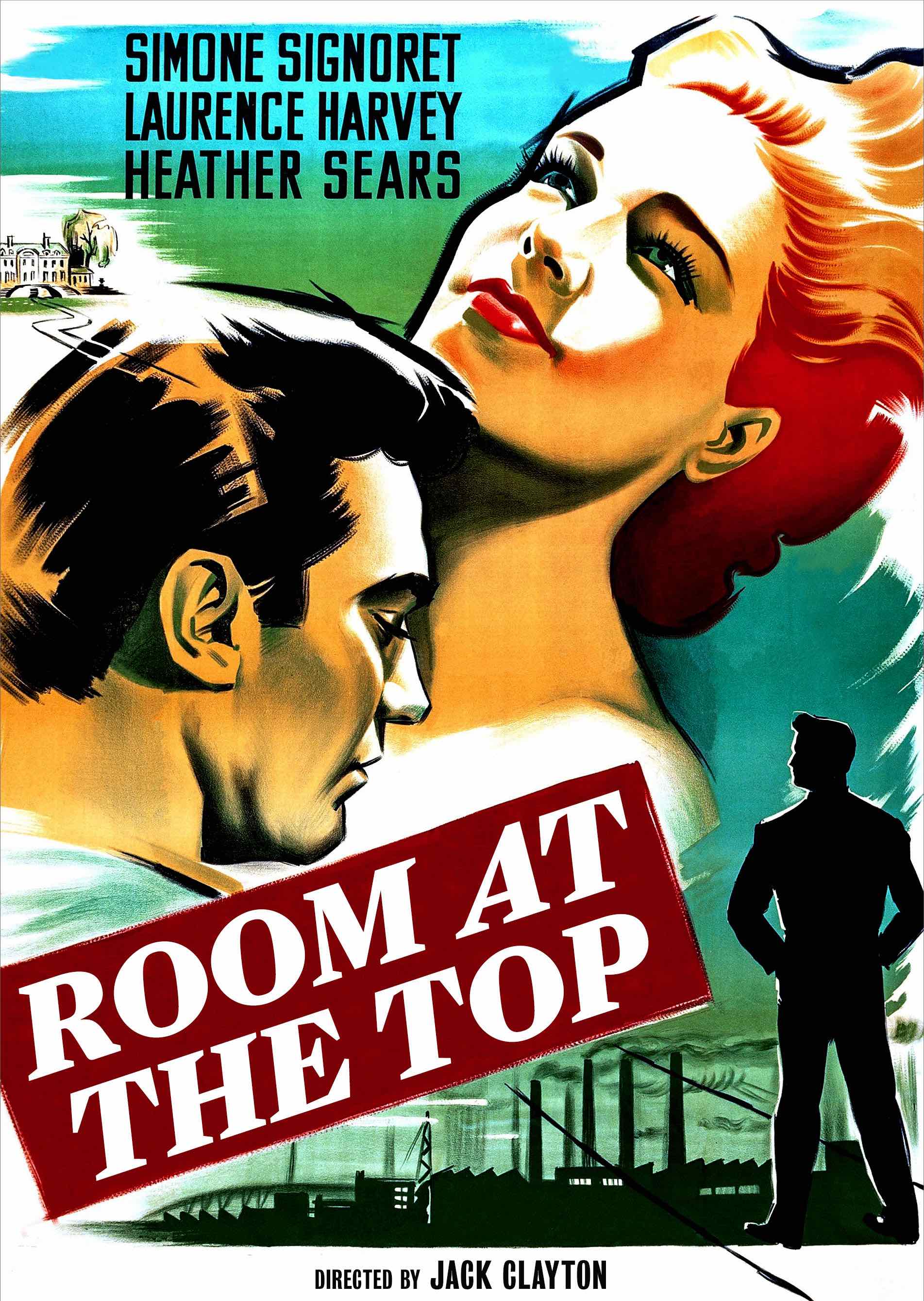

In the canon of great filmmakers that rarely received their due, there are few names that stand as tragically as that of Jack Clayton. Devotees and supporters of the director and his work will be very quick to mention how he had all the makings of a master, but didn’t really amass much of a positive reputation, instead having his distinct artistry labelled as unapproachable, preventing him from ever achieving the greatness he seemed destined to have based on the many films we have that show his remarkable gifts. His masterpiece is undeniably the gothic horror The Innocents, where he manages to make one of the most frightening works of terror ever committed to film – but we can very easily look to his previous film, Room at the Top, which also happened to be his debut into directing features. This is certainly not a film that is nearly as ambitious as some of his other projects – in fact, by all accounts it is very simple and often pedestrian in the story it tells. However, as Clayton demonstrated through his short but impactful career, his approach is one that takes a straightforward premise that would be otherwise forgettable in the hands of a less-skilled director, and transforming them into indelible works of art that stand the test of time, and prove themselves to be incredibly resonant, both for audiences at the time and the many that would go on to discover his work in subsequent decades. Room at the Top is a fascinating character-driven drama with touches of tragedy and romance found throughout, and despite taking on a rather unassuming story, the bold choices that Clayton makes are well worth the time, with the director taking firm hold of the human condition and gradually deconstructing it, exposing its many layers in a way that feels heartfelt, authentic and undeniably relevant.

It’s rather easy to look at Room at the Top as just another melodramatic work of kitchen-sink realism, especially since this occurred right around the time as the social realism movement in Britain was at its peak – several directors, mainly those aligned with the “angry young men” school of artistic thought – used the platform afforded to them as a chance to express their disillusionment with society and directly address its numerous problems from their perspective. It gave rise to some potent socio-cultural commentary on the part of many filmmakers who would go on to become artists cherished for their forthright manner and willingness to get to the core of the social plagues, as they saw it. Clayton was caught between worlds in this regard – his early productions (such as the short films he made prior to making his mainstream debut here) were littered with biting critiques of various aspects of the society he grew up in, but not quite to the point where his realism could be described in the same terms as those found with his contemporaries. He operated on a level more aligned with the early realists, those who sought to find the balance between genuinely representing existence, and describing the many emotions that are evoked by certain circumstances. Less concerned with the outside world, and more interested in exploring the fragile mental states of these characters, Room at the Top is a disquieting psychological journey that finds the nuance in even the most commonplace situations, and in the process becomes an oddly enduring piece of cinema that seeks to be more descriptive than discursive, which immediately situates it in a class of its own, considering the time in which it was set, and the story it was so consistent in conveying.

One can’t have any thorough discussion on Room at the Top without mentioning the performance given by the beguiling Simone Signoret, who has become essentially the part of the film that has been case for the most praise. While the film is led by Laurence Harvey (who is quite good, albeit very limited and lacking the rugged charm we’re told to believe he has in spades), it’s Signoret who commands the screen, playing the melancholic Alice, a profoundly lonely woman who feels even more alienated from the world precisely because she has been forced into a loveless marriage and a career as a low-grade actress in a working-class English town that has very few prospects for a woman like her. Signoret is a truly enchanting actress – her screen presence is so unique, you’d struggle to find anyone who could give the kind of performance she gave consistently throughout her career. Room at the Top was one of her major entry-points into English-speaking cinema, and she is absolutely astonishing, especially considering how the role is, based on a cursory glance, not particularly complex. Signoret sells every moment as if they were some sacrosanct truth, with her eyes reflecting both soaring joy, and deep-seated anxiety that her happiness is only temporary. The moments where Room at the Top succeeds the most are those when Clayton realizes the powerhouse performance he is capable of getting from Signoret, who surrenders herself to playing this tragic character who steals the entire film, shifting focus away from the interesting but far-less compelling protagonist, who ultimately falls by the wayside as a result of the incredible work his screen-partner is doing for most of the film. Ultimately, Clayton understands the potential he was working with, and he brings out the best in everyone involved – and when presented with someone already daring enough to make the choices that Signoret, its unsurprising that this has the most significant cultural cache.

Room at the Top is a film that can be reduced to the characters, since it is very much focused on exploring their innermost quandaries, and deriving dramatic material from their various crises of identity and deep anxieties that inform many of their actions. However, the film is also one that can separated from the specific performances, and instead looked at from the perspective of the more metaphysical themes that persist throughout. More than anything else, Room at the Top is a film about profoundly lonely people, where the conversation is centred around the fact that no one is immune to the restless shuffling that comes with not feeling like you belong, which is something that is all too common in life. Isolation drives much of this film – there are many moments of happiness throughout, where these lonely characters momentarily forget about their strife, which proves to be a fool’s errand, since it doubtlessly returns, even more aggressively than before. This is an intense psychological study that is obviously not overwrought or heavily theoretical, but rather constructed with a masterful control of character, where the intimacy afforded by the director to these individuals at the core of the story gradually go towards making some sincere statements that many of us can relate to, even if the specific aspects of the plot may be more niche. It’s the kind of sincere 1950s British drama that attempts to cut to the heart of the matter without showboating or being too excessive – and the result is something quite special, if not incredibly heartbreaking at many points.

Clayton masterfully penetrates the minds of these characters, presenting their plight in a manner that seems genuine – this isn’t melodramatic for the sake of it, but rather carefully constructed to impart a certain message, which comes across so exceptionally well when we realize that Room at the Top is more of a tragedy than anything else, a heartbreaking drama that takes on a number of different ideas, presenting them to us in a way that carries even more meaning when all that is left is a strong story about a few people trying to make their way through a world they don’t quite understand, following the conventions they have been conditioned to believe as sacrosanct, and gradually becoming a masterpiece of 1950s cinema. The dialogue is brimming with emotion, and is delivered by a gifted cast, led by the charismatic Laurence Harvey and astonishing Simone Signoret, who leaves such an indelible impression through her performance in this film, it’s impossible to imagine anyone else doing this role justice. It’s a simple, elegant drama that traverses perilous narrative territory, and emerges as a heartbreakingly authentic portrait of loneliness and trauma – it isn’t always easy to watch, but it is persistent in its endeavour to be realistic, which is perhaps the aspect of Room at the Top that is most worth noting, and which immediately situates this as one of the more poignant glimpses into the human condition of its era.

Katharine Hepburn once said that all the right actors win the Oscar but for the wrong role. This time they got it right. Simone Signoret was never more compelling as she is here. Hers is a magnificent portrayal where every word of dialogue is shaded with life experience and portent. We know Alice has an extraordinary story and Signoret hints at it but leaves much to our imagination which increases our desire to know this woman and to mourn her untimely demise. A truly great performance

Absolutely agreed. Signoret is an absolute revelation, and one of the most natural, nuanced performances I’ve seen in some while