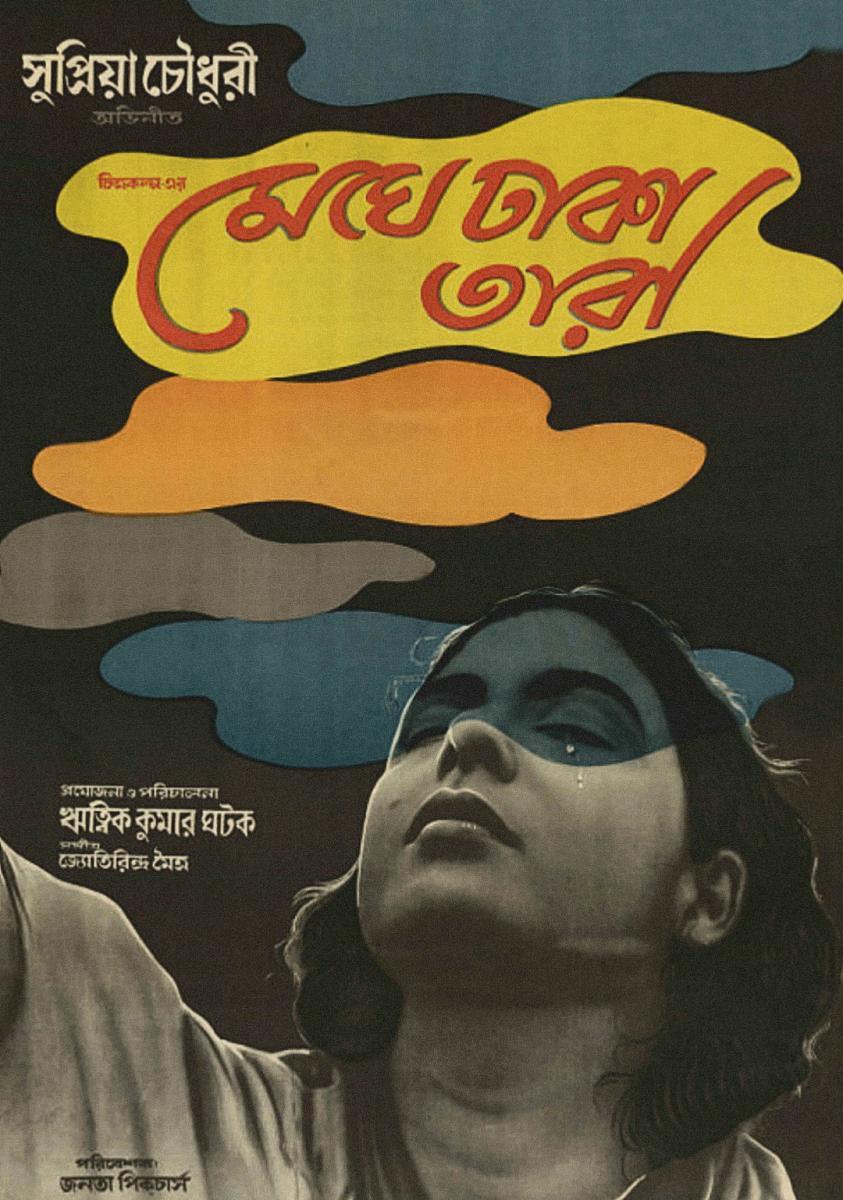

One of the biggest problems with contemporary world cinema is that so much attention is focused on Europe and certain Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea, we don’t often give enough exposure to those nations that often fall by the wayside in many discussions. India has a rich and storied cinematic history, but one that doesn’t always receive the acclaim that it deserves. Other than Satyajit Ray, very few filmmakers from the country make their way into the mainstream discourse – and while this is undoubtedly a broad generalization (since there are many who are doing their part to champion Indian cinema), there is still a long way to go. One of Ray’s contemporaries was Ritwik Ghatak, who has achieved a modest level of acclaim, but still tends towards obscurity. One of his defining masterpieces is The Cloud-Capped Star (Bengali: মেঘে ঢাকা তারা), a riveting drama that follows in the tradition of many of his peers in focusing on social realism as a means to show the trials and tribulations of the working class, and gives some context to a particular period in the history of a country that was gradually emerging from the spectre of colonialism. Bengali cinema has an even more complex history, since the region went through its own individual socio-cultural challenges around this time, which is precisely what makes the work of Ghatak and his contemporaries at this moment such effective storytellers, and established them as essential voices of their generation. It’s not enough to simply praise them – we need to amplify what they said, looking into their particular works and understanding where their intentions lay. Very few films do this better than the present one, and the result is an absolutely astonishing work of fiction in The Cloud-Capped Star, a daring and beautifully-poetic drama that traverses multiple ideas without losing its balance even once.

The Cloud-Capped Star is set in a small town in rural Bengal. An ordinary working-class family resides there, attempting to make ends meet whatever way they can, all the while holding closely onto their particular values, especially in regards to the role each person plays in the household, based on the strict adherence to well-documented social and familial structure. It only stands to reason that there would be those who would go against these principles, such as the protagonist, Neeta (Supriya Choudhury), who is only person with a regular job, and who gradually becomes her family’s breadwinner due to their various problems in earning a living, much to the chagrin of her tutor father (Bijon Bhattacharya), and belligerent mother (Gita Dey), who doesn’t miss an opportunity for deriding her daughter for taking on the familial position that should’ve gone to a man. It isn’t helped by the fact that Neeta’s brother, Shankar (Anil Chatterjee) has very little direction in life, with his ambition being to become a singer, and thus spends his days at the local riverside, singing an array of songs by Rabindranath Tagore, who he claims inspires him. Carrying the burden of her family is far too intimidating for Neeta, and she attempts to soften the tension by becoming steady with her boyfriend (Niranjan Ray), a promising young man who seems to be a perfect match for her, and someone she can depend on. However, she soon learns that nothing can ever be taken for granted, especially when she rapidly spirals downwards, losing everything she holds dear to her, and realizing that every day she is alive is a miracle, since her youth and vivacity is no match for the threat of disease. She does her best to prevent succumbing to the various forces that surround her – familial pressure, social unease and consuming diseases all pose enormous threats to the young woman, who decides that she has chosen the path of progress, and has to deal with any potential consequences that occur along the way.

Social realism in Asian cinema is an area that hasn’t received nearly enough attention – so much is written about this form of storytelling from other contexts, but when it comes to this particular continent, the expectation is for specific kinds of genre filmmaking. This is one of the many reasons why Ghatak is such a fascinating filmmaker, since he was clearly so vehemently against being shoehorned into a particular style or told to craft specific kinds of stories, his films ended up being quite revolutionary based on their own resistance to expectations. The Cloud-Capped Star is possibly his most defining work (at least in terms of being the one that has come closest to qualifying him for more worldwide acclaim), and it’s not difficult to see why it achieved what is far more difficult for a film like this. Throughout the film, Ghatak is venturing fearlessly towards a kind of unfurnished, stark filmmaking that strikes some incredibly raw nerves, and constructs situations that can’t easily be resolved without touching on some more serious subjects, which the director shows absolutely no hesitation towards doing. Naturally, The Cloud-Capped Star doesn’t take itself as anything other than a profound portrait of the human condition, siphoning the very essence of existence into two hours of riveting, heartwrenching drama, in which we gradually become immersed, seeing life from an entirely different perspective. Ghatak isn’t satisfied with just showing his audience – he wants us to become involved in the process. This is precisely what makes The Cloud-Capped Star such a fundamentally powerful exercise, since we’re invited into the lives of these characters, and allowed to view their everyday lives – which are neither overly exhilarating, nor particularly banal, but rather poignant depictions of reality that are often bound by their unimpeachable reality. This kind of authenticity may not be to everyone’s taste – and Ghatak seems to be even more against the process of heightening the situations for effect than Ray (who was already amongst the directors who approached his stories with nothing but validity) – but for those interested in a straightforward but extraordinarily compelling story of postcolonial life, there are few films that do this better than The Cloud-Capped Star.

Ghatak isn’t so much telling a story as he is weaving together a form of visual poetry, which seems very much aligned with the sensibilities underpinning this film, especially in how everything dovetails into a poignant expression of life’s many obstacles. He’s not intent on describing the specific machinations of the life of the ordinary Bengali citizen – as interesting as this may be, it doesn’t really carry much meaning if there isn’t much context behind it. Throughout The Cloud-Capped Star, the narrative ventures inwards, looking at certain themes from the perspective of a regular family dealing with the expected challenges that come with existing at this particular point in history – this form of storytelling is often most effective, since it touches on serious social and cultural themes without once purporting to being the defining, all-encompassing work on the subject. Ghatak doesn’t propose his work to be the final word on anything, but rather just another entry into a movement of filmmakers bound by their relentless pursuit of capturing the spirit of existence through the eyes of the very people who experienced it on a daily basis, witnessing the changes that occurred in the decades following the end of the colonial project, and how even after gaining liberation, there are far more institutionalized problems that tend to have much more indelible consequences, both culturally and psychologically. Not only is this approach far more interesting than anything that could’ve been done with a grander premise, but it also lends the film an enormous amount of credence in how it carries deeper meaning on a range of subjects that barely register at first, but gradually build up to taking over the narrative completely, leading us to be blown away by its subversive means of infusing each frame with a kind of poeticism that doesn’t often find its way into mainstream cinema.

If there’s anything we can learn from what Ghatak does with The Cloud-Capped Star, it’s that the most simple approach is always ideal when dealing with matters of humanity. There’s very little doubt that this film wouldn’t have been nearly as effective had it not been so fundamentally human in its execution. A large part of this finds its way into the characterization of the individuals that populate the film, since a story like the one the director constructed for The Cloud-Capped Star wouldn’t work without believable figures shepherding it forward. At the outset, the family at the core of the film seems like any regular nuclear Bengali family – an older married couple with grown children who are caught somewhere between adolescence and adulthood, and where primary concerns for everyone are matters of finance, in the form of career choices, and romance, in the form of potential marriages (with the two intertwining consistently throughout). Gradually, the film strips away the veneer of convention as we see that this is a family plagued with unhappiness – the father is bordering on senile, and his wife is chronically complaining, to the point where she alienates her own children because of her refusal to see them as anything other than failed representations of what she aspired to have as offspring. Her three children aren’t any more traditional – her oldest daughter refuses to bow to the ideals of domesticity, and her son is a hedonistic man who prefers to imagine a world where he is a singer, as opposed to choosing a substantial career. Each one of the characters in The Cloud-Capped Star is achingly realistic, and the performers tasked with them are absolutely incredible in bringing them to life. Supriya Choudhury stands out amongst them, playing the part of Neeta with a striking sincerity that never fails to inspire absolute awe in any viewer who finds themselves transfixed with her unique blend of innocence and resilience, becoming her defining features and make Neeta such a compelling protagonist. Stylistically, The Cloud-Capped Star isn’t particularly special (even if there are some moments of absolute beauty scattered throughout), so it only stands to reason that the aspect of the film we tend to remember the most are the characters through which the story could be told, which is almost certainly the most resounding merit in an already incredible film.

The sheer poignancy pulsating through The Cloud-Capped Star should not be underestimated, since so much of what makes this such a powerful film resides in these moments of almost ethereal meandering, whereby Ghatak is commenting on some complex themes through the guise of a poetic narrative that touches on so many resonant ideas. Combining heartfelt melodrama with sequences of magical realism (such as the sporadic moments where we see Shankar walking through the countryside singing, which gives the film a necessary boost of energy, and allows its progress to be noted through his growing confidence in his skills, one of the many small nuances Ghatak infuses into the film) was a challenging task, but the director does so beautifully, finding the truth in a very difficult story. Yet, what lingers the most about The Cloud-Capped Star isn’t the mechanics of its plot, or the various strands of dialogue that carry a great deal of meaning, but rather the emotions evoked throughout it. Despite the bleak nature of the story, Ghatak composes an exceptionally hopeful film – this film would not have been nearly as meaningful had it not carried some sense of impossible optimism, and even when it is spiralling towards complete despair, there is some feeling of hope. Inarguably, this film doesn’t have a traditionally happy ending – if anything, the climax is the most haunting aspect of the entire film. However, if we strip away the ambiguities accompanied with the ending, and instead look at what message it conveys – that of defeating the odds and surviving by any means possible – we can easily understand why this is such a profoundly effective work of cinematic realism. Ghatak truly made nothing short of a masterpiece with The Cloud-Capped Star, a powerful and heart-wrenchingly beautiful social drama that finds the hope in the most impossible of situations.

Bengali cinema has its own importance in the Indian film industry. It comprises talented directors, actors, actresses, cameramen, music directors and other technicians. Bengali cinema goes through a lot of experiments before its execution. It is rich with variety of subject matter.

https://www.indianetzone.com/2/bengali_films.htm