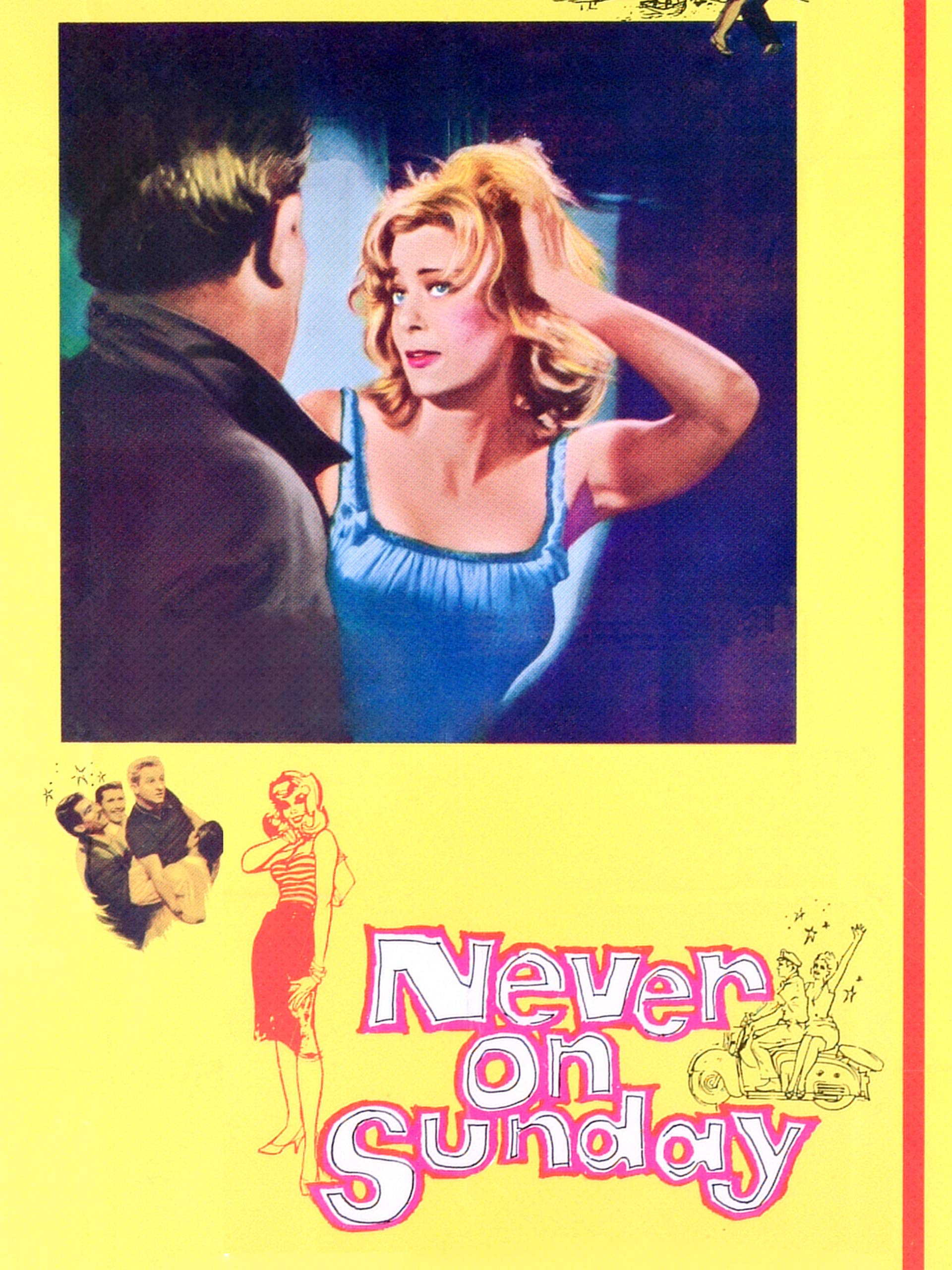

There are just some films that fill you up with a sense of joy and wonder, with their most prominent quality being the fact that they’re able to captivate the viewer and take them on a beautiful journey, without needing to become too focused on the details. One of the most exemplary instances of this is Never on Sunday (Greek: Ποτέ την Κυριακή), the utterly charming romantic comedy written and directed by Jules Dassin, who also stars as one of the two leads in what is essentially a work of nothing but unrestrained glee. Produced at quite an uncertain time in European history, but done for the sole purpose of spreading happiness more than anything else, Never on Sunday is such an absolute delight in every conceivable way – beautifully romantic, hilariously funny and exceptionally composed by a director who had a clear passion for the very simple story he was conveying here, Never on Sunday is a true marvel of a film. It may not be too complex, and it can be perceived as somewhat pedestrian both in theory and execution – but where some would find fault with such a simple approach, others will certainly appreciate it, especially when we realize that just because the premise isn’t too convoluted, doesn’t mean there isn’t a wealth of discussion to be had throughout – the director finds the charm in what is essentially a formulaic comedy, and brings out a poeticism that may not be evident from the start, but strikes us right where it is necessary, leaving us thoroughly transfixed and enamoured by this stunning work of fiction. Undeniably one of the best comedies produced at the time, and a film that has remained as resonant and touching today as it did sixty years ago, Dassin truly captured lightning in a bottle with Never on Sunday, which has an abundance of heart, a wealth of laughter and an underlying message that can match any of those present in the more prestigious, prosaic works produced around the time, and crafted one of the decade’s most exciting, rivetting works of fiction that never settles for anything other than the absolute best, and then some.

Even without getting too embroiled in the specifics of his career in terms of the controversy he endured as a part of the Hollywood blacklist, we can still note how profoundly influential (and incredibly prolific) he was as a filmmaker who worked in various areas of the industry, and quite effectively. Never on Sunday is amongst his most acclaimed work, and it’s certainly not difficult to discern why this is – it’s a gloriously triumphant comedy that never neglects the underlying melancholy, creating a vivid tapestry that is incredibly resonant, even if we ourselves don’t have much knowledge or experience of the sensations Dassin is describing here. There are essentially two primary components to Never on Sunday – that of the romantic comedy, and the culture-shock satire, both of which are interwoven into the narrative in an oddly natural way, to the point where it feels entirely authentic. Dassin masterfully controls the humour, keeping everything very restrained, but not once avoiding the inherent joy that can be derived from these situations. Partially a comedy of manners accompanied by broad overtures of the most gorgeous sophisticated romance imaginable, Never on Sunday has such an immense powerful approach to a very simple premise, we tend to forget that we’re actually watching a film – this is quite possibly one of the most genuine romantic comedies, insofar as it seems to be dismantling the familiar traditions, and instead venturing outwards, towards the more realistic side of the story. Set to the backdrop of beautiful Greek landscapes, you’d think this was set to be just another formulaic comedy about two individuals from wildly different cultures finding love against the odds – but through perfectly-calibrated humour and a wonderful sense of authenticity, Dassin is able to do something so extraordinarily touching, you’d be remiss to not see the immense value embedded in the film, which propels it forward and makes it so utterly memorable.

Of course, like with any great romantic comedy, we don’t always tend to remember the humour when it has ended, but rather the vessels for it – and in this case, Dassin derives one of the best performances of the 1960s from Melina Mercouri, who is so incredibly enchanting, you’d struggle to find a more charming performance from this period, especially considering how European stars were rapidly emerging as favourites of the arthouse, with Dassin finding something so unique in the actress, a wild spark that simply didn’t exist across the pond. Mercouri was born to be a star, and every moment of Never on Sunday is brimming with energy when she is on screen. A beguiling presence that draws us in with her mysterious allure, but keeps us captivated through her unprecedented warmth and incredibly sensitive understanding of the character, Mercouri is simply astounding. It takes quite a bit to make such an outrageous character seem so natural, but through a blend of her eccentric charm, and the director’s ability to harness the actress’ natural abilities, Never on Sunday becomes an enduring experience precisely through the performance Mercouri gives. Dassin may not have been a particularly charismatic actor, but he does match her beat-for-beat throughout the film, with his impish Homer (named after the famous mythologist and author) being a great screen partner for Mercouri’s formidable Ilya. Their chemistry is absolutely astounding (and it’s hardly a surprise they married later in the decade, and remained together until Mercouri’s death), particularly since Dassin understands that despite being the focus of the film, Homer isn’t a compelling character, and the true protagonist is Illya, so nearly all of the attention is given to her, rather than having the male lead dominate. It’s an oddly progressive approach, but when you have someone so dedicated to every nuance of her performance as Mercouri was, it’s difficult to argue against it in any way – and when we realize the depths to which the actress goes to humanize Ilya and make her a beautifully complex character, someone who can tell an amusing anecdote in public, and then in the next scene, privately sing a passionate ode to her desire to lead a normal life one day with “one, two, three, four” children, it’s impossible to not feel entirely taken by her performance.

There’s a simplicity to this film that makes it worthwhile, a kind of sophisticated restraint that prevents it from ever becoming too ensconced with its own message. Many have drawn comparisons between this and George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (with the characters in this film even mentioning the classic story at one point), particularly in how it focuses on a supposed intellectual becoming fascinated by a young, working-class woman who is a part of what he perceives as a lesser profession, and attempts to educate her to the ways of decent society, using his experience (all garnered from textbooks and high-class rendezvous) as the grounds for his knowledge, not realizing that Illya is far from complacent, and will openly rebel against any attempts to placate her or the joie de vivre that defines her entire existence. Never on Sunday becomes less of a film about someone trying to transform another into an ideal vision of what a woman should be, but rather a clever subversion of this trope, a hilarious romp that turns the entire principle on its head and shakes out all of its pretention. Consider the ending, where Homer finally professes his love to Ilya, who expresses similar sentiments, but immediately falls into the arms of another man (who has always admired her, regardless of her profession), leaving the brokenhearted American to board his boat and sail off, hopefully having learned that you can’t always change someone to fit into your own ideal version of the world. It’s a tricky tightrope that Dassin is walking with this story, and there are some moments where it seems to be built on objectifying its female characters – but when we realize this was all done as an underhanded method of challenging narrative conventions, an entirely new layer of meaning is added to it. Dassin finds a lot of value in a smaller premise, and gradually explores new depths of this story, finding new ways to express his admiration for both the culture he is so enthralled by, and his enigmatic star who he tasks with bringing it to life, and ultimately creates a thoroughly unforgettable work of romance.

It’s not particularly complex storytelling, but it doesn’t need to be – like any great romance, all the audience needs is a charismatic pair of leads, a strong story and good writing, and the rest of the work is easily accomplished along the way. This may not strike potential viewers as a particularly original film – how many times have we seen the same pattern of cultures colliding into a beautiful romance, all set against the backdrop of the Mediterranean? Where Never on Sunday deviates is in how it is incredibly proud of its simple approach – it knows it doesn’t need to be anything particularly revelatory, and instead focuses on finding the grace in the most inconsequential moments. Normally, we’d remember the broad strokes of romance, or the funniest jokes – but in this film, what lingers the most are those details occurring in between the major moments, the small glances, the quiet remarks and the general sensation of unhinged joy that pervades nearly every frame of this film. It’s a staggering one, and one that approaches perfection quite often – the music by Manos Hatzidakis captures the spirit of the culture so beautifully, the cinematography by Jacques Natteau portrays the gorgeous landscapes with such elegance, and Dassin’s script sets the tone for what is to become a truly unforgettable comedy that carries such an incredible sincerity, we’re not likely to find anything quite as upbeat as this without some effort. What a wonderful realization it is to learn that we live in a world where something so joyful can exist.