I’ve written quite a bit about theatre over the past few weeks – screen adaptation of the works of Tennessee Williams, William Gibson and Eugene O’Neill were all subjects of recent conversations, mostly since I’ve been covering years where these kinds of films were in vogue, with nearly every work of major American theatre getting some kind of cinematic treatment around this time. However, when thinking of masterful works of American theatre, you’d be remiss to not mention Lorraine Hansberry’s incredible 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun, quite simply one of the finest works of twentieth-century literature ever produced. The play was subsequently adapted into a 1961 film, with much of the same cast transposed from stage to the screen, and under the careful and humane direction by the prolific Daniel Petrie, it became a pivotal work of 1960s cinema, a warm and heartfelt exploration of the myriad of themes Hansberry introduced in her original production, which are now permanently etched onto film for future generations to bear witness to. By all means not much more than a direct adaptation of the play, A Raisin in the Sun is a staggering work that benefits from many unique qualities – a brilliant ensemble of actors, a masterful attention to detail and the willingness to open this play up to the world around it, without losing any of the value embedded in the source material. A powerful, poignant and heartbreakingly honest work of mid-century literature, A Raisin in the Sun is simply extraordinary, and Petrie did exceptionally well in reminding audience of the value found in Hansberry’s words and the message they convey with such immense ferocity, which still holds up as powerfully today as it did the moment the curtain lifted over half a century ago, where history was essentially made.

One can easily wax poetic about how brilliant an adaptation of the original work A Raisin in the Sun was, but it would just be reiterating the same conversations about the intricate tightrope a director has to walk in order to prevent allegations of doing very little else than just filming a stage production. The stage and screen are two very different platforms, and there’s more freedom afforded to those working in the latter medium – and considering A Raisin in the Sun is a play known for being restricted to mostly one location, Petrie was given the chance to open the play up to the wider world, which isn’t something that is taken for granted, since this adaptation does exceptionally well in keeping the value of the original work intact, never having it become overwhelmed by the cinematic form. There’s always the danger of a film like this being seen as unchallenging artistically – but I dare anyone to experience this version first-hand and not be utterly compelled by the choices the director and the rest of his collaborators here employ in bringing Hansberry’s story to the screen. The brilliance here doesn’t lie in the broad strokes, but the small details that aren’t very noticeable at first, but eventually flourish into the striking moments that leave the most profound impression. Directing isn’t always about making the most audacious choices, but sometimes entails taking existing material and finding new ways to represent their ideas without abandoning the original meaning – and perhaps the idea of celebrating someone who essentially just supervised the direct translation of a work from one medium to another (an assertion that is horrifyingly reductive, but which has often been levelled against films like A Raisin in the Sun) may seem odd, there is a lot of value in what Petrie does here, especially in the moment intimate moments, where Hansberry’s words are made even more impactful by the presence of a lingering shot, or an unexpected close-up on one of the actors, showing the raw emotions underpinning these sequences that simply wouldn’t be present on stage.

Naturally, what tends to linger the most with these stage-to-screen adaptations are the performances – theatre is primarily an actor’s platform, so its hardly surprising that these films are often most notable for the performances that they capture. Employing almost the exact same cast as the 1959 stage debut, A Raisin in the Sun has some of the most incredible actors of their time appearing across from each other. The decision to bring the actors who originated the roles to the screen adaptation is yet another choice that tends to be derided when discussing these kinds of adaptations – allegations that it points towards laziness and unoriginality persist, which ignores the fact that sometimes the most compelling performances come from those who helped pioneer the roles, or got to know the characters in ways that those hired for a film adaptation may sometimes be unable to do. A Raisin in the Sun is one of the many times when this approach worked spectacularly well – not only were some of the actors cast already established in the industry as a whole, but it gave others a chance to work in a prestigious drama that served to be a showcase for their talents. Whether as co-leads or in supporting roles, each actor in A Raisin in the Sun is brilliantly-cast and give remarkable performances. The effervescent Ruby Dee is wonderful as the conflicted Ruth, a woman who yearns for a happy life, but always seems to have drawn the short straw with everything, and even upon learning of her second pregnancy, she is more despondent, since despite wanting another child, she knows how unfeasible it is to bring another child into her family’s economic situation. Diana Sands contrasts Dee as her slightly younger sister-in-law, a hopeful medical student who sees a world outside the dreary apartment walls, and wants adventure, becoming involved in issues far bigger than her. Dee and Sands play very different roles, but bring such depth and pathos to their respective characters, they manage to play off each other very well.

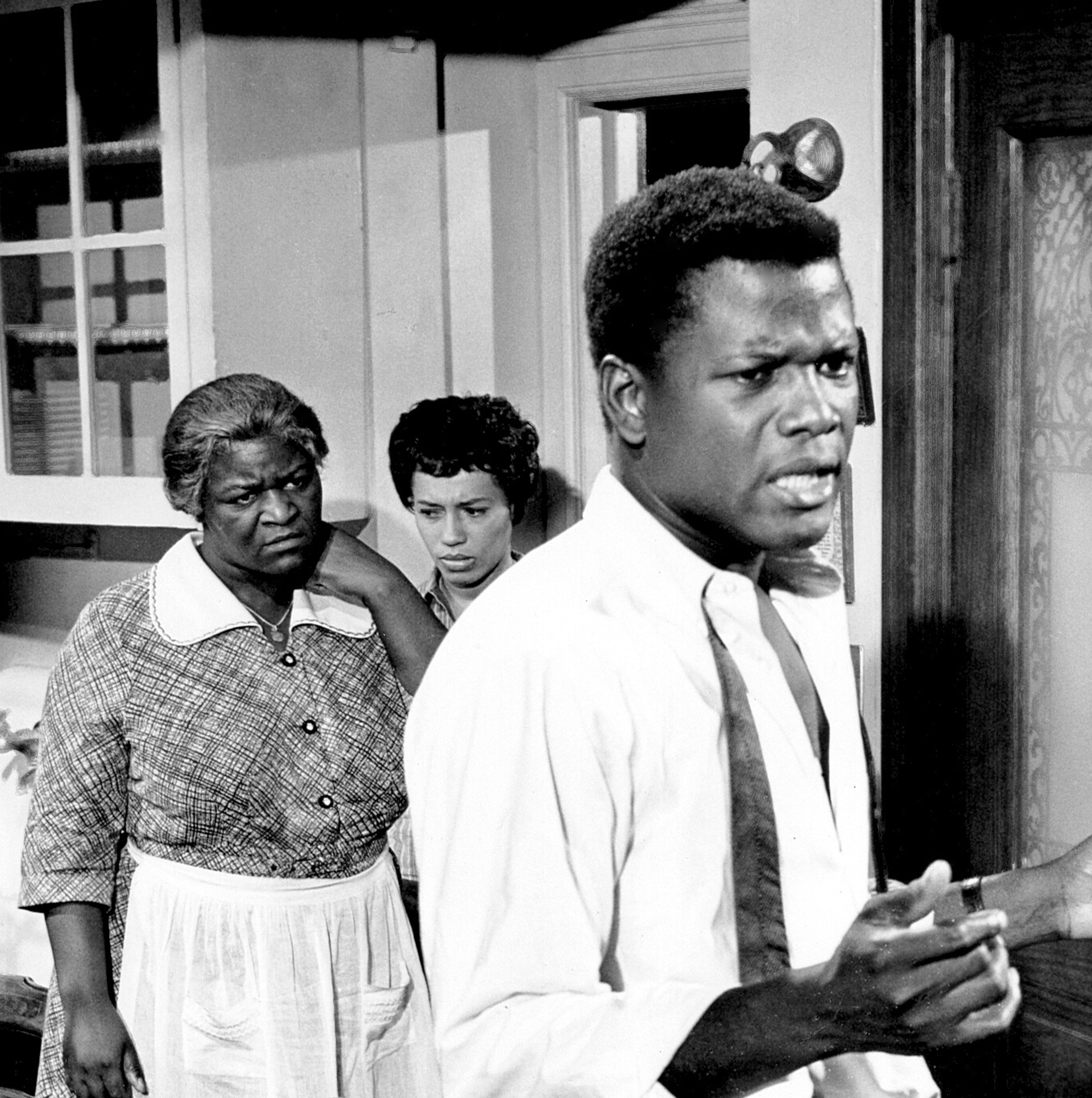

However, the two most memorable performances A Raisin in the Sun undeniably come from the two that are most often noted as being the stars of the piece – Sidney Poitier and Claudia McNeil, who are singled-out most frequently as the most significant performers in the piece. Poitier is an actor who I’ve expressed nothing but admiration for over the years – his manner of commanding any room he was in has persisted throughout his career, and made him quite simply one of the greatest actors to ever work in the medium, with both his pioneering spirit to go where many at the time wouldn’t have dared, as well as his longevity that stretches from the Golden Age right to just before the current era, making him a formidable presence, both on-screen and off. In A Raisin in the Sun, he is playing one of his most vulnerable characters – Walter Lee Younger is not a particularly intelligent man, nor does he have many discernible moral scruples or sense of ethics. Instead, he is an ordinary man doing his best to survive. I am in perpetual awe of Poitier, and even when he is showing a slightly different side in A Raisin in the Sun, where his character is intentionally more callous (I’m hesitant to call him unlikeable since his flaws are not necessarily enough to invalidate the more positive aspects of the character), he is delivering impeccable work – his moments of humour are heartfelt, his dramatic monologues are absolutely shattering. It’s not the performance that defined Poitier’s career, but its certainly all the proof one needs that he could do absolutely anything. McNeil was best known for her work on stage, and had only appeared in a minor film role prior to this adaptation – and somehow, through sheer unexpected force, she delivers a definitive performance of 1960s cinema. Her work in A Raisin in the Sun is absolutely staggering – she starts as the comic relief, a boisterous and funny elderly woman who insists that “she ain’t meddlin'”, even when it is clear that she is, but eventually becomes the focus of the film – every moment McNeil is on screen is a revelation. She carries more depth in even the most inconsequential lines than any actors do in entire performances, and brings such warmth to the film. A Raisin in the Sun may best be remembered as a vehicle for Poitier, but there’s no way of denying that the story is undeniably McNeil’s – she brings a quiet intensity to the part that you rarely see, and Petrie managed to catch lightning in a bottle with this performance, which is just brimming with humanity that so rarely manifests in such a profoundly effective way.

A Raisin in the Sun is a truly impressive work, and an essential piece of American filmmaking. Daniel Petrie truly managed to adapt Hansberry’s play in a way that allowed the serious discussions on race and social perspectives to be explored to its full potential, with the film never eliding a single moment in favour of being more cinematic. It’s an undeniably simple film – it confirms the idea that sometimes the best films are those produced with a strong story, great actors and the good sense to use the camera to capture these moments, both the verbal and nonverbal ones, and turn them into something meaningful. Undeniably, the film may be a lot more straightforward than many others – however, its impact comes in the message it conveys, and how the director uses an incredibly strong set of ideas to make a statement, channelling them through the work of one of the most impressive ensembles of the 1960s – absolutely everyone in A Raisin in the Sun is doing some of their best work, each one fitting into this world in a way that is meaningful, bringing an authenticity to these roles that would be difficult to achieve had they not taken some intrepid risks in how they interpret their characters. The discussions central to A Raisin in the Sun, both within the context of the play and the discourse surrounding what it is saying, make this work a vital piece of social commentary – and in adapting it to film, these artists created a way for all audiences, whether past, present or future, to witness the sheer might of this production in a profoundly moving way. Provocative, riveting and incredibly powerful, this is a work that must be experienced – a stage production is always going to be a priority, but this film adaptation is just as incredible, and manages to preserve some of the finest performances of its era, which only makes this version of A Raisin in the Sun something that should be actively sought out by anyone with an interest in resonant, moving cinema.