Robert Stroud (Burt Lancaster) has been sentenced to death for the murder of two men. A young and rebellious felon, he holds very little remorse for his actions and is willing to take the punishment long before he’s going to regret his actions. However, based on a successful petition run by his mother (Thelma Ritter), Stroud has his sentence commuted to lifetime imprisonment, where he is to remain in solitary confinement for the rest of his life. Over the years, his parole requests are frequently denied, which doesn’t seem to be nearly as bothersome to him as it would appear, since he has resigned to the fact that the rest of his life is going to be spent in prison. A chance encounter with an injured sparrow leads Stroud to find his passion for life, and over the course of his decades in prison, he becomes a dedicated bird-lover, and over the course of a few years accumulates a wide variety of pets that he keeps in his cell, building makeshift cages and doting on them. He eventually becomes possibly the country’s leading expert on bird diseases after he ventures into studying them as a result of a bout of illness causing his beloved creatures to die en masse. Over the decades, he grows to adore these beings, finding a great deal of solace in them – and with the exception of the kindhearted guards who take a liking to him, a fellow inmate (Telly Savalas), and the strict but lenient warden (Karl Malden), Stroud’s only companions seem to be his pets, who bring him the comfort he needs, especially when his mother proves to be vehemently against her son’s freedom, and the young woman who takes an interest in Stroud (Betty Field) starts to see his flaws while trying to reconcile her own adoration for the man. For over half a century, Stroud does what he can to survive, living a lonely but compelling life that may have been far from ideal, but gave him the satisfaction he craved, granted the circumstances.

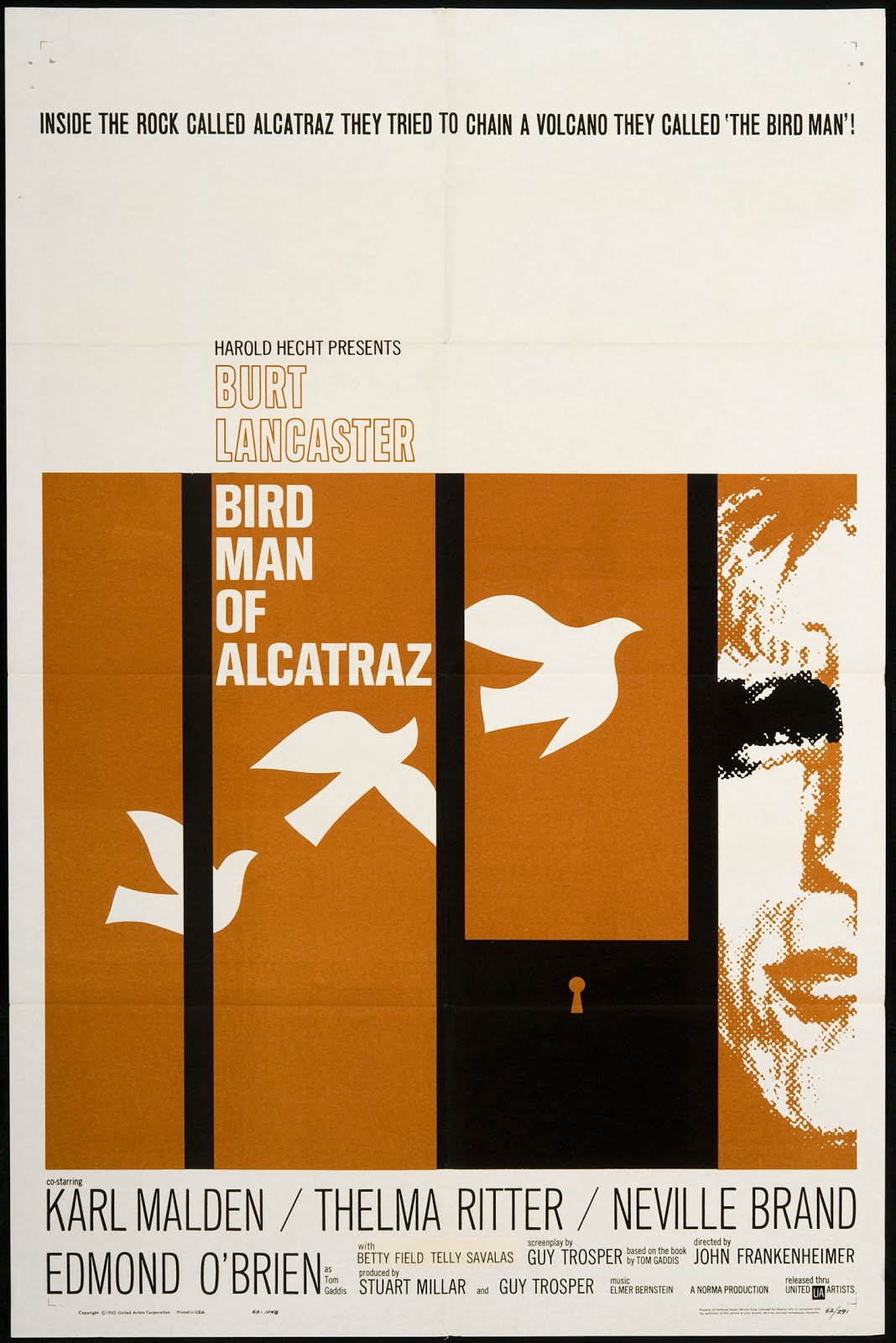

The story of Robert Stroud is a profoundly fascinating one – a prisoner that came to be referred to as the “Birdman of Alcatraz” (despite it being well-documented that he didn’t keep birds while imprisoned in the titular prisoner), accounts of his life vary – for the prisoners and other personnel that encountered him over the years, he was a far less-pleasant person than the retrospective portrayals of his life would suggest, and his story, while deeply compelling, has been one that has been great fictionalized over the years. The main culprit for this is John Frankenheimer’s adaptation of Thomas E. Gaddis’ 1955 book about Stroud, that sought to look at his many decades of incarceration, and the activities that he pursued throughout this period. Inarguably, Birdman of Alcatraz is something of a miscellany of ideas, some of which work while others are not quite as successful. It’s a clear attempt to turn the life and career one of America’s most famous prisoners (I use the word “famous” with a caveat since this sentiment is often reserved for notorious criminals known for their actions prior to being caught, while Stroud was someone whose entire folkloric legacy is centred around his residence in various American prisons in the early twentieth-century) into an inspiring story of triumphing over adversity and finding the hope in a challenging situation. Honestly, it isn’t our place to determine whether or not Stroud deserved such treatment, but rather an opportunity for us to have access to his story, which (despite the bickering around its accuracy) is incredibly fascinating, and functions a lot better than it probably should have, considering the challenges that were likely compounded on this film, and which serve to make it a very polarizing, but still quite fascinating, work of cinema that may not hit all the beats it endeavours to, but at least makes a concerted effort.

Decent, but uninspiring is perhaps the best way to look at Birdman of Alcatraz, which does manage to say something, but takes some time to get there, by which time the audience is either fully encapsulated by this story or resigned to a story that seems singularly uninterested in being much more than passable. Frankenheimer certainly didn’t make a bad film in any way – some tremendous aspects are employed quite regularly, and the final product is entertaining enough, even if it may not have aged in a way that feels particularly resonant by later stands. A traditional biographical drama that hits all the expected notes, Birdman of Alcatraz is a fine film and one that actually may mean more in theory than it does in execution. The story of Stroud is certainly a captivating one – according to the epilogue of the film, he was entering his fifty-second year in the prison system, with his misdeeds putting him in prison for the vast majority of his life. Considering his time behind bars stretched from 1909 to 1963, he was distanced from the world for many major events – both World Wars, the Great Depression and the beginning of the Cold War. All the way, he was locked away, living a life he brought on for himself. This alone would’ve made a deeply compelling film – so it seems something of a shame the story really converged into fictionalizing his work as an amateur ornithologist, which is a lovely novelty, but loses its charm once it becomes clear there’s not going to be anything particularly worthwhile in this side of the story. Logically, for a film that carries a title like Birdman of Alcatraz, it would be strange for it to deviate all that far from this side of the story (even if, as we’ve noted, it already isn’t particularly truthful – Alcatraz appears as the coda to the film, rather than the main setting). Less of a film with clear shortcomings, and more one with its general construction being too innocuous to truly make an impression, Birdman of Alcatraz is successful for what it is – but its what it could’ve been, but never quite reaches, that makes this slightly disappointing as a film.

There comes a moment in Birdman of Alcatraz when one realizes this wasn’t entirely constructed to be a meaningful exploration of the story of Stroud, but also a vehicle for Burt Lancaster, who was at his peak at this time, and was consistently being given projects the emphasized his brooding masculinity while putting it in contrast with his talent for playing more complex characters. Stroud is certainly a compelling subject, and Lancaster is naturally terrific in the role, and despite some moments where the cogs are clearly visible in his performance, he is reliably wonderful in the part. It’s the film around him that doesn’t give him all that much to do – having a talented actor in the main role doesn’t mean the film around him can falter, and while some actors can elevate the material solely on their charisma or persuasive talents, regardless of the quality, Lancaster (at this point in his career) often depended on a strong story to ignite the brilliance. He gives a decent performance here, and there are some moments where he is actually quite excellent, most of them occurring later in the film, where Lancaster has substantially calmed down and allowed the story to take flight, rather than trying to infuse every frame with sweltering masculinity, undercut by some great tragedy that really isn’t there. Lancaster was an actor who was at his best when he wasn’t trying too hard to make an impression – some of his most impressive performances (such as Frank Perry’s The Swimmer and his two collaborations with Luchino Visconti, The Leopard and Conversation Piece) were solid achievements, mainly because it gave Lancaster some thoughtful characters to play, and which didn’t depend on him carrying the story on his own, but rather working in tandem with the premise to evoke something meaningful. He was a fantastic actor, but he did need the material to push him towards greatness from time to time, and I’m not quite sure that was all present in Birdman of Alcatraz, as interesting a performance as it may have been.

This is by no means a criticism of his actual performance, but rather the problems facing Birdman of Alcatraz – ultimately, the most bewildering aspect of this film is how it treats Stroud as some American hero, a pensive and thoughtful man with great moral grounding a keen understanding of the unspoken ethics of the world he has been locked away from. Prison films can be a challenge when it comes to meaningfully portraying these characters, since it doesn’t inherently lend itself to likeable characters, especially in a story like this, where the main character’s guilt isn’t contested, but rather an unimpeachable fact. Making Stroud an endearing character, especially considering the testimonies to his more belligerent, unkind nature, was a major mistake, and while Lancaster does very well in the part, the film as a whole often feels slightly misguided – rehabilitation and reformation is definitely not a bad approach to such a subject, but when the vast majority of the project depends on the audience actually becoming invested in the character enough to actively root for him, to the point where we lose sight of his actual reasons for being in prison, and have him hailed as some tragic hero, only because the US penal system refused to allow him to keep birds, seems somewhat bewildering. The constant need to infuse so much emotion into the film seems ill-conceived as well – consider one of the later scenes, where Stroud decides to drink some of his own chemicals in an attempt to become inebriated, followed by a hard-cut to the prisoner drunkenly opening the cages of his birds and proclaiming that he is providing them with the “false illusion of freedom” is, in practice, an interesting concept – but it simply doesn’t work in the film, and this is far from an isolated incident, as so much of the film is composed of these disjointed scenes that seek to add nuance to a character that ultimately just may not have been all that interesting in the first place.

Ultimately, Birdman of Alcatraz is perfectly adequate – it isn’t a major film in any way, and it does have some glaring problems that prevent it from ever coming close to greatness, but that doesn’t invalidate the fact that it does have something to say, even if it doesn’t manifest in a particularly successful way throughout. Understandably, the idea of crafting a film around the story of a man whose livelihood while in prison was his passion for birds is an alluring concept – the film was produced during a period in which many biographical dramas had to have some deeper meaning, so the focus being on a man whose interest with caged animals mirrored his own lifelong sentence was certainly not an ill-conceived idea for a film. Where the problem comes is how the film treats Stroud – he’s far too tenderly approached in the film, shown as a complex man who lived a moral life (despite the film making it quite clear that he was a cold-blooded killer) and was the victim of a system that was just far too unfair to him, just because the regulations advocated against keeping pets in prisons. To say Birdman of Alcatraz goes too easy on the main character isn’t all that absurd – with the exception of a few interactions, Stroud is shown as an upstanding individual who can get anything he wants by simply asking, receiving it on the virtue of his reputation as a decent man, which runs counteractive to the entire purpose of the story at all. We often forget we’re watching a prison film, since all the tension and focus on the consequences of crime become so inconsequential to the story, and all the conflict is restricted to the most uninteresting commentary about one man’s attempt to defy the odds and raise his birds. There’s an interesting story to be told about Stroud and his time in prison – you don’t spend half a century behind bars, especially during one of the most tumultuous eras in history, and not have a few stories to tell. The emotion is forced, the characters not all that interesting and the story itself passable but unremarkable. Birdman of Alcatraz is a sufficient way to pass the time (even if, at 150 minutes, it far too long), and despite not always living up to its potential, it does well in being a very conventional biographical drama – the problem is, this story deserved a far more interesting and dedicated approach, one that is far less saccharine and predictable, and more direct to the broader issues that underpin the story. These never materialize, and all we’re left with is a passable, but highly forgettable, work that tries to say something, but doesn’t quite succeed.