In the seaside hamlet of Boulogne-sur-Mer stands a quaint apartment, where four individuals find themselves one ordinary evening. The residents there are Hélène Aughain (Delphine Seyrig), a former housewife who has found her passion in collecting and selling antiques, and her adult stepson, Bernard (Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée), who is a veteran of the Algerian War. Their guests are Alphonse Noyard (Jean-Pierre Kérien), one of Hélène’s former lovers who she hasn’t seen since 1939, and his young mistress, Françoise (Nita Klein). What was supposed to be a lovely dinner and overnight visitation turns into roughly two weeks, where the four individuals find themselves questioning a lot more than they bargained for when planning this casual rendezvous. Each one of them is holding onto some secret – Hélène and Alphonse pretend to be pleased to see each other, but harbour a deep resentment that interacts with their quiet adoration for the other, a result of their sudden separation, a situation neither is willing to fully take responsibility for. The trauma of the past haunts each one of these people – and whether the lingering effects of the war, or the challenges faced by a pair of former lovers who find themselves questioning the most fundamental matters of the heart, it becomes clear that the antiques are not the only remnants of the past littering that small apartment, with everyone doing what they can to overcome their individual traumas, even if they all acknowledge how singularly difficult this may be, and how it requires a kind of introspection absolutely none of them are willing to fully commit to, at least not until they know for sure that they’re going to get the answers to the impossibly difficult questions they have been longing to ask for years.

In the seaside hamlet of Boulogne-sur-Mer stands a quaint apartment, where four individuals find themselves one ordinary evening. The residents there are Hélène Aughain (Delphine Seyrig), a former housewife who has found her passion in collecting and selling antiques, and her adult stepson, Bernard (Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée), who is a veteran of the Algerian War. Their guests are Alphonse Noyard (Jean-Pierre Kérien), one of Hélène’s former lovers who she hasn’t seen since 1939, and his young mistress, Françoise (Nita Klein). What was supposed to be a lovely dinner and overnight visitation turns into roughly two weeks, where the four individuals find themselves questioning a lot more than they bargained for when planning this casual rendezvous. Each one of them is holding onto some secret – Hélène and Alphonse pretend to be pleased to see each other, but harbour a deep resentment that interacts with their quiet adoration for the other, a result of their sudden separation, a situation neither is willing to fully take responsibility for. The trauma of the past haunts each one of these people – and whether the lingering effects of the war, or the challenges faced by a pair of former lovers who find themselves questioning the most fundamental matters of the heart, it becomes clear that the antiques are not the only remnants of the past littering that small apartment, with everyone doing what they can to overcome their individual traumas, even if they all acknowledge how singularly difficult this may be, and how it requires a kind of introspection absolutely none of them are willing to fully commit to, at least not until they know for sure that they’re going to get the answers to the impossibly difficult questions they have been longing to ask for years.

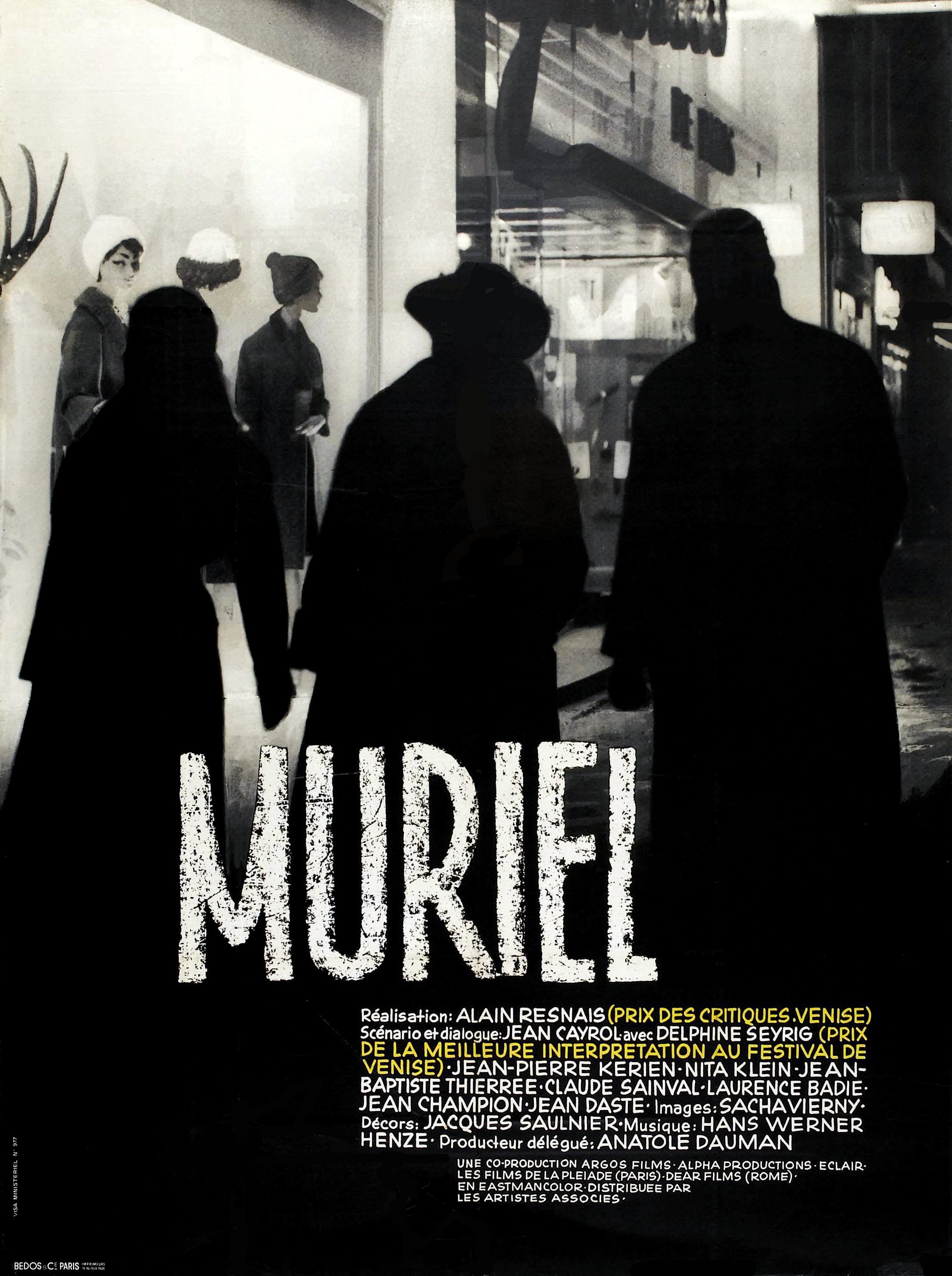

The films of Alain Resnais were known for a few fundamental qualities – their magnificent beauty, both in form and the stories they told, gorgeous use of narrative structure and an elegantly subversive approach to structure. They were also often quite difficult to categorize, existing somewhere between grounded human drama and ethereal, vaguely surreal metafiction. Muriel, or the Time of Return (French: Muriel ou le Temps d’un retour) is one of his most significant work, and while not lingering in the zeitgeist with the same reputation as some of his other films such as Hiroshima, mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad, it is undeniably some of his finest work, a hauntingly beautiful story that touches on themes of memory and trauma in a way that can only come from a filmmaker whose command of his craft, both in terms of conceiving of brilliant ideas and executing them with a kind of immense artistic integrity that is daring without being pretentious. As is the case with the vast majority of films made throughout his career, Resnais’ work here is truly remarkable, both in how he takes on such a seemingly simple set of concepts, siphons them through a highly-original theoretical framework that he establishes from the startling first few moments and persists to the very final shot, and produces an exceptionally original work of early postmodernism, at a time when French culture (not only cinema) was right at the forefront of challenging the boundaries of philosophical theory, creating works that dare to be different, and in the process produce entirely new ways of thinking, both of art and more metaphysical concepts such as the past, and our relationship with it. Identity, trauma and history all blend together in this film, which dares to go further than many others would have even attempted, resulting in a work of unmitigated brilliance.

Perhaps describing a film like Muriel in such a way seems hyperbolic, but once the viewer is under the hypnotic power of this story, it becomes perfectly clear as to why Resnais is often considered one of the most profoundly brilliant filmmakers of his generation. Like many of the director’s works, Muriel is a film that requires some level of acclimation from the viewer – while he could never be considered someone who made self-indulgent or convoluted films, Resnais was known for creating situations where the audience has to navigate some treacherous narrative territory in order to get to the heart of the story, which only makes a film like this all the more compelling and is complicit in portraying the emotional depths plumbed by a director whose unquestionably strong understanding of the human condition made for truly poignant, and achingly beautiful, works of cinema. Muriel is a film that requires undivided attention from the audience – passivity has no place in the oeuvre of Resnais, but considering how immensely transfixing this film is, there’s very little difficulty in surrendering yourself to its unconventional brilliance. An extraordinarily challenging film in all the ways that a work of great experimental fiction should be, Muriel takes some getting used to, but once you’re fully-enveloped by the narrative, and the meaning starts to become clear through the gradual unravelling of the closely-guarded secrecy that covers the film, and slowly erodes as we venture further inwards, finding new meaning to what we considered to be the truth. As is the case with a lot of what the director has said in his work, particularly through these earlier films in which he was provoking the confines of the narrative form, one doesn’t necessarily need to abandon logic (as they would in more experimental works at the time), but rather prepare to have their perspective shifted as they experience a very different, but still undeniably recognizable, version of reality, which is the exact kind of artistic brilliance Resnais peddled throughout his career.

The central thesis of Muriel is that time is not linear, at least not in the way we tend to believe it is. The past, present and future are all occurring concurrently through Resnais’ vision, as he employs a certain non-linearity to the proceedings that makes for initially bewildering viewing (entirely by design), but ultimately works towards creating an insightful portrayal of the bizarre nature of human psychology, and the various machinations that come in the situations depicted here. Time isn’t a single path, but rather a multidimensional journey, with the past lingering as a spectre, consistently reminding us of previous traumas, and the future a distant concept that seems to regress further the more we actively venture towards it. Life is amiss from the first moments of this film, with the first indication of this non-traditional approach coming in the fact that the titular character is never seen, instead functioning as a remnant of the past, a figurehead of the collective trauma that relates directly or indirectly to each of these characters. Psychological theory remarks on the idea of the “present-absent”, person, place or thing that haunts our memory, being persistent influences in our life without tangibly manifesting – normally related to trauma theory, this concept works towards clarifying how each of these characters function, especially when centred on the long-deceased, almost anonymous young woman who died during the Algerian War, the scars of which are present in each of these characters. Resnais is well-aware of the implications that he lays down in this film – a great deal of commentary surrounding it has been focused on noting how not a single frame in this film seems wasted, and the director makes sure to go to every possible length to give the viewers something to think about, without preaching or making it overtly clear the direction he intends to go, which only contributes to the general laissez-faire approach of building this film on each viewer’s individual interpretation from the paltry prompts we receive throughout, which enriches the experience of working through this film and its overall message.

Cinema loves trauma, as its an experience that the majority of us can unfortunately relate to in some way, and is thus fertile ground for fascinating psychological explorations that are both riveting and profound. Resnais is fully aware of this, as it formed the foundation for much of his work (such as the aforementioned feature films, and his short documentary Night and Fog), with his work being insightful, but still deeply challenging. He traverses the delicate boundary between grounded reality and the ethereal realm of memory with immense ease, taking on a sense of strikingly powerful melancholy that makes an impression without being overwhelming or heavy-handed, which serves this film exceptionally well and makes it the complex masterpiece it is regarded as today. Less of a film, and more of a cinematic essay on a multitude of complex themes that are not necessarily unique to this story, but rather realized through radically different methods that were both incredibly natural for the artistic period in which this film was made, and ahead of its time, Resnais’ amalgamation of numerous intricate topics results in something quite extraordinary, and deeply satisfying for those who take the time to go along for the adventure into the depths of the human condition. A slow-burning domestic melodrama simmering with socially-charged insights into the psychological complexities of our shared species, Muriel is quite an achievement. It’s an incredibly enigmatic film, and a large part of what makes it a riveting experience is the process fo the audience decoding it – and whether you are compelled by the resolution (if you can refer to the haunting climax as such), or left even more bewildered, it’s absolutely worthwhile to immerse yourself in this unconventional, but incredibly compelling, version of reality presented to us by one of the most important filmmakers of any generation.