Frederick and Alice Thornton (Nigel Davenport and Isabel Dean) are a pair of British merchant expatriates in Jamaica who are raising their five children in one of the small coastal towns that they occupy as part of the growing European settlement that shows very little sign of stopping, especially through the colonial expansion that is fueled by the Industrial Revolution. After a vicious storm tears apart their home and puts their family in danger, they decide to send their children back to London, where they can be taken care of, and put out of harm’s way, as it is clear that the island isn’t affording them the structure, nor the safety, any parent would desire for their offspring. However, their journey home turns out to be far more unpredictable than they thought, as their humble passenger ship is soon taken over by a gang of vicious pirates, under the command of the brutish Captain Chavez (Anthony Quinn) and his first mate, Zac (James Coburn), a pair of ruthless villains who are willing to do anything to line their pockets, even if it means taking any resources they can find by force. A misunderstanding results in the children being locked away in their ship, only to be discovered by their captors after the pirates have already made their escape – and so begins an unexpected friendship between the Thornton children and Captain Chavez, who finds himself softening through his interactions with his innocent new companions, whose youthful naivete is an enormous change of pace for the motley crew of malicious, violent sea-bandits, who come to terms with their own dormant humanity when tasked with caring for a group of children who threaten to derail all of their grandiose plans – for better or worse. Over the course of a few weeks, they all grow closer, but the inevitability of rescue causes them to rethink their relationship, and how they’ll acknowledge this bizarre turn of events that absolutely none of them could’ve possibly predicted.

Frederick and Alice Thornton (Nigel Davenport and Isabel Dean) are a pair of British merchant expatriates in Jamaica who are raising their five children in one of the small coastal towns that they occupy as part of the growing European settlement that shows very little sign of stopping, especially through the colonial expansion that is fueled by the Industrial Revolution. After a vicious storm tears apart their home and puts their family in danger, they decide to send their children back to London, where they can be taken care of, and put out of harm’s way, as it is clear that the island isn’t affording them the structure, nor the safety, any parent would desire for their offspring. However, their journey home turns out to be far more unpredictable than they thought, as their humble passenger ship is soon taken over by a gang of vicious pirates, under the command of the brutish Captain Chavez (Anthony Quinn) and his first mate, Zac (James Coburn), a pair of ruthless villains who are willing to do anything to line their pockets, even if it means taking any resources they can find by force. A misunderstanding results in the children being locked away in their ship, only to be discovered by their captors after the pirates have already made their escape – and so begins an unexpected friendship between the Thornton children and Captain Chavez, who finds himself softening through his interactions with his innocent new companions, whose youthful naivete is an enormous change of pace for the motley crew of malicious, violent sea-bandits, who come to terms with their own dormant humanity when tasked with caring for a group of children who threaten to derail all of their grandiose plans – for better or worse. Over the course of a few weeks, they all grow closer, but the inevitability of rescue causes them to rethink their relationship, and how they’ll acknowledge this bizarre turn of events that absolutely none of them could’ve possibly predicted.

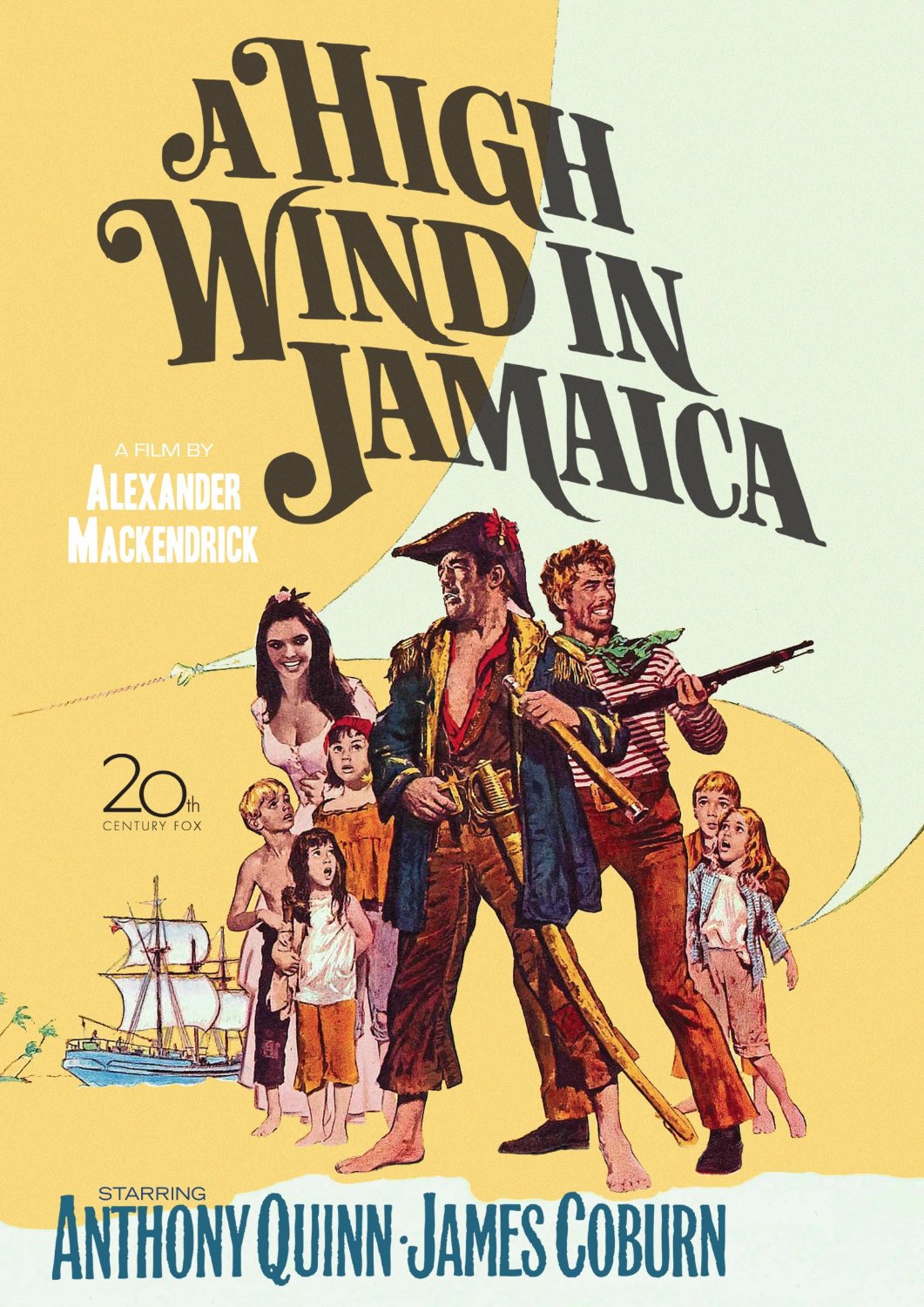

Alexander Mackendrick was a strange choice to adapt the famous novel by Richard Hughes – by no means a bad director, he was instead someone known more for his carefully-calibrated satires (The Sweet Smell of Success) and his outrageous dark comedies produced for Ealing (such as The Man in the White Suit and The Lady Killers) – so to be the choice to helm an ill-fated reboot of what was supposed to be a bold, colourful adaptation by Disney (which eventually fell through) was bizarre but oddly inspired at the same time. A High Wind in Jamaica is one of the more interesting works to come out of the period between the peak of cinematic epics and the shift towards more subversive forms of storytelling, inspired by the industry being right on the precipice of the New Hollywood movement, where audacity was not only an admirable trait of a select few, but rather a defining quality of a whole generation of filmmakers that were inspired by the alternative form of narrative that someone like Mackendrick himself was complicit in establishing (making his involvement in A High Wind in Jamaica all that more fascinating). An ambitious film that occurs somewhere at the perfect intersection between style and substance (defaulting to either side at different points of the film, which is far less jarring than it could’ve been), Mackendrick’s adaptation is a fascinating voyage into the adventure genre that may be a stone’s throw away from brilliance but overcomes minor narrative flaws to become a charming, enthralling work that deftly avoids overwrought sentimentality, and finds the perfect balance between family-oriented entertainment and more serious fare, which is not very common for a film like this, with many similar works at the time being forced to compromise by choosing one or the other. Ultimately, A High Wind in Jamaica is a terrific film, a partially-hidden gem that is begging for another reevaluation, as it is nothing short of an absolute delight in many ways, an enthralling adventure that keeps the audience engaged and the story wonderfully lucid.

The adventure genre is one that has undergone many different iterations over the course of Hollywood history – from the silent swashbucklers to the enormous, generation-defining blockbusters, the industry has always found solace in knowing that these kinds of films bring comfort and joy to global audiences, with their blend of adrenaline and bold visual style being almost universally beloved, particularly when they’re made well. A High Wind in Jamaica is a film produced during an ambigious time in the industry’s history, where no one was really sure of how to approach such a story – the era of epics being seen as events were winding down with the rise of more auteur-driven cinema taking preference for many studios. This gave Mackendrick a great deal to work with in regards to A High Wind in Jamaica, being tasked with picking up the fragments of a long-gestating film that was passed through various channels in Hollywood, only to fail to materialize until it was brought to him to salvage by piecing together what remains, which he did with his extraordinary vision that hadn’t been clear, even though he did dip into slightly similar territory in films such as the maritime-themed The Maggie and Sammy Going South (forming something of an unconventional trilogy of traversing the seas and encountering a range of eccentric characters along the way). This was by far his most ambitious production, and it ultimately does show in both the impressive scope and slight shortcomings that persist throughout – and while certainly never weighed down by its narrative or structural problems, A High Wind in Jamaica did suffer slightly from a case of being caught between periods – this is a Golden Age swashbuckler occurring at the verge of a bigger movement, and there are moments where it finds itself sampling beautifully from both, but also becoming inconsistent in some key moments that prevent it from being as thoroughly audacious as its premise would suggest. It doesn’t invalidate the value of the film, but rather gives us more insight, not only into the making of this specific work but perceptions of the genre overall.

What is perhaps most striking about A High Wind in Jamaica is how it is clearly a film that comes from the heart. Mackendrick (working from a screenplay by a gang of writers, one of them being Ronald Harwood, the versatile scribe behind some of the most memorable genre films of their respective eras) constructs a film that is positively brimming with soul, with everything from the production design (simple but thoroughly effective) to the way the story unfolds, being a masterful example of the well-worn adage of “less is more” applying to even the boldest films. A High Wind in Jamaica logically never attempts to go too far with the material to the point where it becomes unrecognizable, while still being a humble attempt to venture into a deeper form of storytelling. It contains a very simple premise, and with the exception of the thrilling first act (which is by far the strongest part of the film, bordering on being a pitch-perfect intersection of comedy, adventure and compelling drama), it is a slow-burning look into a cast of fascinating characters that are brought to life through wonderful performances, with a huge portion of this film’s success resting on the people tasked with bringing it to the screen. Anthony Quinn is at his most empathetic as the vicious pirate with a heart of gold, playing Captain Chavez with rugged charm and dashing alternative heroism that Quinn often exploited throughout his storied career. James Coburn is a formidable scene-partner, playing the sycophantic Zac in a way that he functions as the comic relief, but also has his own emotional arc, and is far more than just a malevolent sidekick to Quinn’s anti-hero. The children are adequate but unremarkable, functioning as adorable anchors for the story but not necessarily standing out in any discernible way, often being overtaken by the two leading actors, and a cast of scene-stealing supporting players, such as the effervescent Lila Kedrova, who is given minimal screentime but is still wonderfully exuberant as the sympathetic brothel mistress who momentarily serves as the children’s maternal figure. The heart of the story lies in these characters, so it only makes sense that the film realizes this in personifying them beyond simply being adventure-narrative archetypes, instead developing them much further and with more sincerity than we’d expect from a film like this, which is perhaps its most significant merit.

A High Wind in Jamaica is an undeniably effective film – perfectly calibrated as both an adventure and character-driven drama, it manages to flourish into a poignant look into the trials and tribulations of a set of individuals expanded from the pages of pulpy swashbuckler novels, translating them into the visual medium in a way that is beautifully lush, but not without some kind of substance. Alexander Mackendrick had an eye for detail, and working within the confines of a much bigger story, he managed to put together a compulsively watchable film that keeps the audience utterly enthralled from beginning to end. It may be accused of being too quick in establishing Chavez as a jagged but lovable protagonist (but when you have Anthony Quinn at his most heroic, it’s difficult to view the character as anything less), or that it may drag somewhat after the core of the story has passed, but there’s a rugged charm to the film that overcomes small issues such as these and replaces them with a steadfast, thrilling escapade that is diverting, but not without its own unique depths. It occupies a distinct, but highly-ambigious, period of blockbuster filmmaking, and if anything, it’s relative obscurity makes it a perfect candidate for rediscovery – there will eventually come a time when A High Wind in Jamaica is reappraised as an unconventional but incredibly fascinating work of riveting drama – and until then, we should celebrate it as the hidden gem it is.