Stanley Ford (Jack Lemmon) is a wealthy cartoonist who enjoys the life of a bachelor – his company is normally restricted to his personal butler, Charles (Terry-Thomas), and a number of random women who Stanley meets regularly for passionate rendezvous that rarely last longer than a single evening. He has amassed his wealth through the syndication of his widely-beloved comic strip, which he often bases on his own life and experiences, even going so far as to take part in huge adventures in order to write about them from a place of fundamental experience. However, he is about to embark on the most unexpected adventure of his career when, after a drunken party, he wakes up to discover that he’s gotten married. The bride (Virna Lisi) is an enigmatic Italian woman who does not speak any English, and who immediately embraces the idea of an Upper West Side lifestyle, with the luxury and extravagance it offers being extremely appealing to a young, penniless immigrant like her. Stanley is not particularly enamoured with the idea of sharing his life with someone, especially not a woman who has an insatiable penchant for luxury and insistence for changing his way of living. The situation is impossible for Stanley to navigate, and it’s only a matter of time before Charles retreats, not being interested in working for a married couple. Divorce is not an option according to his wife, and not even his trusted lawyer, (Eddie Mayehoff) can offer any assistance, as he believes having a wife will give Stanley something more worthwhile, and add meaning to his life, which is certainly an area in which the two men differ. It turns out that there needs to be alternative ways to end the marriage – and Stanley starts to realize that the boundaries between fact and fiction can always be blurred with the right approach, and a lot of planning, which he is more than willing to do in order to regain his previous life.

Stanley Ford (Jack Lemmon) is a wealthy cartoonist who enjoys the life of a bachelor – his company is normally restricted to his personal butler, Charles (Terry-Thomas), and a number of random women who Stanley meets regularly for passionate rendezvous that rarely last longer than a single evening. He has amassed his wealth through the syndication of his widely-beloved comic strip, which he often bases on his own life and experiences, even going so far as to take part in huge adventures in order to write about them from a place of fundamental experience. However, he is about to embark on the most unexpected adventure of his career when, after a drunken party, he wakes up to discover that he’s gotten married. The bride (Virna Lisi) is an enigmatic Italian woman who does not speak any English, and who immediately embraces the idea of an Upper West Side lifestyle, with the luxury and extravagance it offers being extremely appealing to a young, penniless immigrant like her. Stanley is not particularly enamoured with the idea of sharing his life with someone, especially not a woman who has an insatiable penchant for luxury and insistence for changing his way of living. The situation is impossible for Stanley to navigate, and it’s only a matter of time before Charles retreats, not being interested in working for a married couple. Divorce is not an option according to his wife, and not even his trusted lawyer, (Eddie Mayehoff) can offer any assistance, as he believes having a wife will give Stanley something more worthwhile, and add meaning to his life, which is certainly an area in which the two men differ. It turns out that there needs to be alternative ways to end the marriage – and Stanley starts to realize that the boundaries between fact and fiction can always be blurred with the right approach, and a lot of planning, which he is more than willing to do in order to regain his previous life.

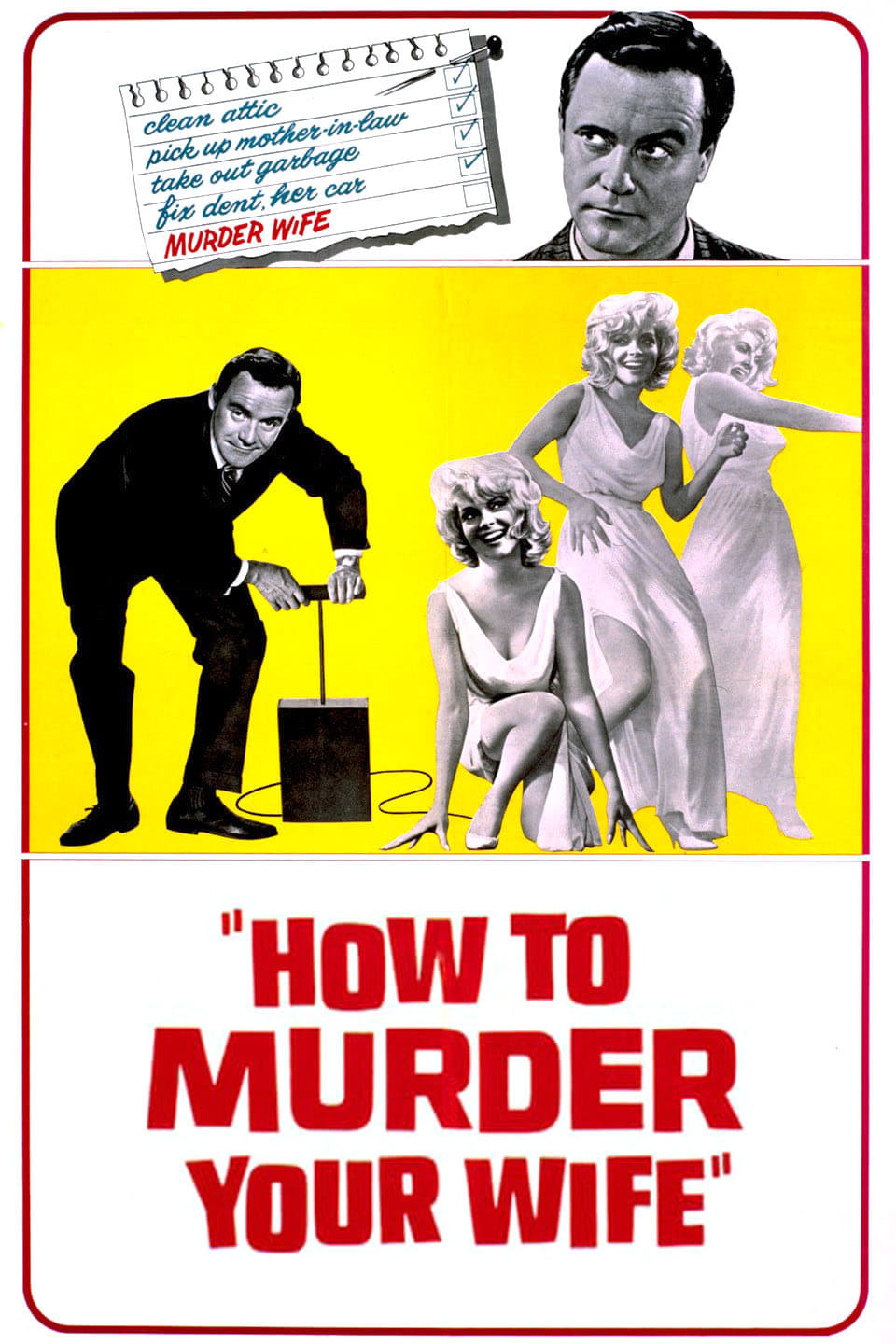

How to Murder Your Wife is an absolute delight – one of the greatest English-language dark comedies of the 1960s, it is the kind of subversive satire that many American filmmakers were often too apprehensive to make, especially in an era where the audience superceded the art, and all intentions needed to be in service of the consumers and their desires. A film about fundamentally despicable characters existing in a version of the world that seems not too detached from reality is not something that audiences were thought to be particularly responsive to at the time, which persists as a major problem for mainstream American cinema, which always has seemed to be driven by a set of standards that make a story like the one at the core of How to Murder Your Wife almost unheard of. Even the title itself is amusingly rebellious and hints that this film is not going to be the traditional charming fare that viewers were accustomed to. Even by today’s inarguably more lenient standards, this is still an extraordinarily risky film, and while its approach may be distinctly old fashioned (there’s something so charming about these 1960s comedies that often are most successful as time-capsules of a particular time and place, rather than being timely accounts of modern life), the message that ferociously pulsates throughout the harrowing hilarity is still very much a controversial one, in the best possible way. However, as important as it may be to construct a film about likeable characters in well-meaning stories when looking at this film, a work of singular genius in so many ways, it becomes clear that even the most abhorrent individuals can be extremely endearing if the story around them is well-made and composed with the dedication that Richard Quine and screenwriter George Axelrod bring to this darkly hilarious tale that takes aim at love, marriage and murder – but not necessarily in that exact order.

What is most interesting about How to Murder Your Wife is how this is clearly the product of an entirely different time, and could never be made today, solely on the fact that it feels remarkably dated on the surface. The film takes aim at marriage and domesticity, presenting women as the villains, and allowing a man to get away with a proverbial murder, based on a rousing speech about how limiting the institution of marriage is. However, the film counteracts its questionable morality with the clear correlations with bleak satire, which is almost entirely what this film is built on. Unlikable characters rarely ever occupy every frame of a film quite like they do here, which gives the film an edge that was somehow both ahead of its time, and impossibly regressive, which was entirely purposeful. Axelrod, in putting this story together, is not attempting to give some deep, insightful portrayal of modern American society, and from the very first moment of the film, it’s clear they’re presenting the audience with a fiendishly dark version of reality that is theoretically plausible, but beyond morally wrought, which is a fascinating contrast that the film could have easily faltered in exploring. How to Murder Your Wife is something of an intrepid piece of cinema, because there were far too many risks associated with this film for it to be seen as a particularly easy film to sell, and the fact that it managed to get made with such a daring title and premise, indicates that there was something far more interesting underpinning this film, which it explores with a kind of acidity that situates it outside of the majority of mid-century American studio comedies, which were always driven by a sense of decency, and even if a cad occupied the central role, they were never as villainous as the protagonist is here, and the consequences were undoubtedly paid, to give heft to the levity. How to Murder Your Wife seems to be singularly uninterested in this, and goes in another direction, resulting in a splendid, original and extremely inventive comedy of manners, despite not seeming to have any of its own.

Beneath the bizarre approach to the institution of marriage and the broad intentions to challenge many of the most cherished notions of modern romance, are a trio of exceptional performances that bolster this film and make How to Murder Your Wife such an enthralling experience in several ways. Jack Lemmon occupies the main role of Stanley Ford, a hedonistic man who is driven by his own self-indulgent desires and has never really grown up past his adolescent years, having the grace and insight of an immature teenager, rather than a man who has amassed the fortune and status that he has. Lemmon was the perpetual everyman – he was beyond likeable, charming in a very sincere way, and could play any character since his natural talents allowed him to occupy a vast array of individuals, real or fictional. However, he does challenge himself to playing one of the rare villains of his career (in the same year as his memorable turn as the cartoonish Professor Fate in Blake Edwards’ The Great Race), and does exceptionally well, specifically since Ford is a character that is morally ambigious more than he is outright evil. The film does tend to be kinder to Lemmon’s character than normal, never having him pay the consequences for too long, and even when he is disadvantaged, he does manage to pull himself out of it. He’s got wonderful chemistry with Virna Lisi, who is excellent as the nameless Mrs Ford, bring such warmth and humour to a role that could have easily just pandered to her stunning beauty, rather than her immense talents. She’s incredibly charming and brings an ethereal elegance to a film that is often preoccupied with a range of despicable characters. Finally, legendary character actor Terry-Thomas is an absolute riot as Lemmon’s valet and confidante, with his uptight demeanour and unique diction making him one of the most memorable aspects of the film. Its no surprise that the film dips in quality when Terry-Thomas’ character makes his exit, as he truly was the heart of the film, and by far the funniest aspect, so it’s not surprising that the film begins and ends with him, as everyone involved knew exactly what a gem of an actor he was and gave him the chance to once again command the screen with his immense charm. However, the entire cast of How to Murder Your Wife, including those in very small roles, are astonishingly good and contribute exponentially to the success of this fantastic film.

One of the most interesting generic ancestors of How to Murder Your Wife would probably be the seminal Arsenic and Old Lace, a film that blends the good-natured absurdity of screwball comedy with the vitriolic humour of much darker work, often verging on the realm of psychological thriller, while remaining as effervescent and charming as the most upbeat comedies produced at the time. There have been many films with the same principles produced since then, but How to Murder Your Wife was something of a revolutionary piece – not necessarily unique, as it wasn’t the first to establish that great comedy can be derived from subverting standards and flirting dangerously close with immorality, but it was one of the few made at the time that presented it without needing to add some kind of gravitas to the themes. This is simply a dark comedy that is content with being shocking, and even when looking at it over half a century later, it remains an effectively deranged portrayal of domesticity, creating a deceptive sense of security that plunges the viewer into a truly demented story. It’s almost admirable the extents to which How to Murder Your Wife managed to avoid moralizing, and with the exception of the final scene in which there is a resolution, clearly the work of the studio demanding something of a happy ending to a film that didn’t really need one, the film is almost entirely built out of an unhinged, maniacal humour that is as potent today as it was then. It deals with challenging the common romantic tropes that were inherent to the genre after decades of well-meaning comedies that present married couples as the epitome of happiness and what every individual should aspire to, and shows how there is something underlying these idyllic scenarios that are far from utopian. Arguably, the film does tend to present all the wive characters as nagging women whose only discernible quality is the power they hold over their husbands, which they normally use to satiate their luxurious desires.

Somehow, How to Murder Your Wife manages to be one of the few comedies that is equal parts regressive and progressive, finding the perfect balance that works for the story its telling. The originality doesn’t come in the story, which is often a by-the-numbers comedy of misadventure, but rather in how the film approaches some darker subject matter, without ever becoming arid in its own right. Rather, it’s a buoyant comedy with terrific performances, a wonderful sense of humour and a kind of self-awareness that evades convention in such a way that it borders on being entirely resistant to the standards that it is often pressured to abide by. It is an imperfect film, and there are certain moments that seem to be jarring in a modern context, but its nonetheless a fascinating piece of 1960s comedy that is not apprehensive to the idea of being darker than other thematically-similar films, as well as tackling subject matter that is fundamentally more challenging than what many would expect, but comes across as strangely heartfelt when perceived from the perspective of fundamental humanity that the film seems to be secretly built upon. It never crosses into moral turpitude and retains an elegance that makes it an enthralling experience, and when you consider how perfectly-calibrated this film is to the time in which it was made, and contrast it with the more modern view of romance, you can see the roots of a kind of playful approach to love and marriage that wouldn’t be clear for quite a while, making How to Murder Your Wife something of a revolutionary film that pioneered a sub-genre of comedy that has now become commonplace, but is still as exciting as it was in this rebellious, unforgettable dark comedy.