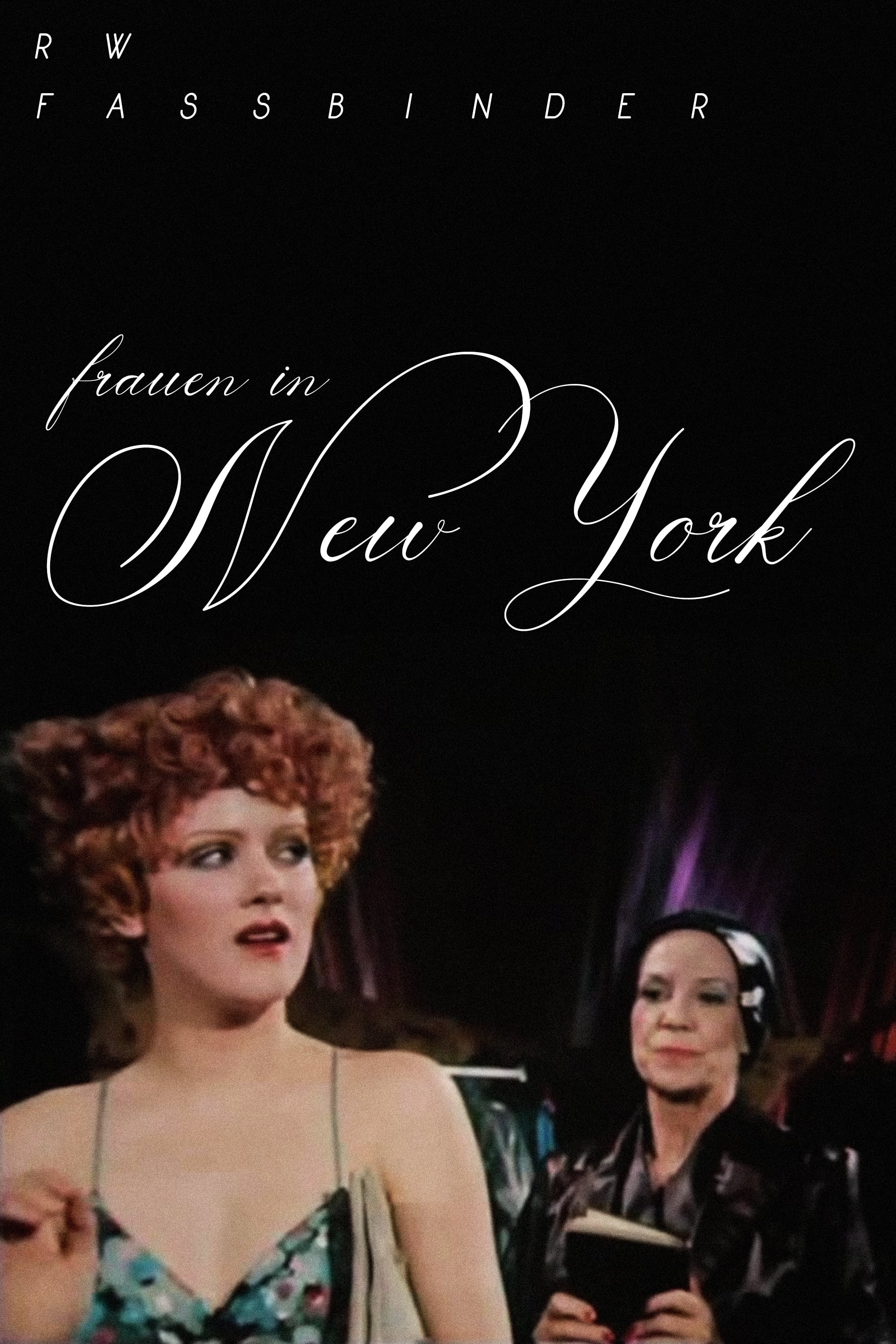

In looking at the history of women-focused cinema, there are few films that represent as seismic a shift into looking at female issues as George Cukor’s The Women, the 1939 adaptation of Clare Boothe Luce’s revolutionary stage production of the same name. Cukor was one of the most influential directors of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and whose work often gave female characters the attention many other films often struggled with. The same can be said for another director who made his debut decades later but still demonstrated a keen understanding of the importance of putting female characters at the centre – Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Unsurprisingly, these two directors have something quite remarkable in common, insofar as they both adapted Luce’s play into their own films. Fassbinder’s version, a filmed production of the play, carries the title Women in New York (German: Frauen in New York), and while it is certainly nowhere close to the dynamic masterpiece of the Cukor film, it is nonetheless a riveting exploration of the machinations of a group of Upper West Side socialites and their various moral and social transgressions that take up most of their time. Fassbinder was an immensely prolific director, and there are almost far too many masterpieces associated with his name to list – so it only makes sense something as audacious as an adaptation of one of the great plays of the twentieth century would remain so obscure, even when working with one of his most potent ensembles. However, the reasons for this aren’t entirely foreign – it is a fascinating relic and something that really functions as more of a novelty for Fassbinder completists, rather than a film that stands on its own merits. Nonetheless, Women in New York is one of the director’s most fascinating experiments and certainly doesn’t disappoint if you’re in search of the raw ambition the director peddled consistently throughout his short but prolific career.

In looking at the history of women-focused cinema, there are few films that represent as seismic a shift into looking at female issues as George Cukor’s The Women, the 1939 adaptation of Clare Boothe Luce’s revolutionary stage production of the same name. Cukor was one of the most influential directors of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and whose work often gave female characters the attention many other films often struggled with. The same can be said for another director who made his debut decades later but still demonstrated a keen understanding of the importance of putting female characters at the centre – Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Unsurprisingly, these two directors have something quite remarkable in common, insofar as they both adapted Luce’s play into their own films. Fassbinder’s version, a filmed production of the play, carries the title Women in New York (German: Frauen in New York), and while it is certainly nowhere close to the dynamic masterpiece of the Cukor film, it is nonetheless a riveting exploration of the machinations of a group of Upper West Side socialites and their various moral and social transgressions that take up most of their time. Fassbinder was an immensely prolific director, and there are almost far too many masterpieces associated with his name to list – so it only makes sense something as audacious as an adaptation of one of the great plays of the twentieth century would remain so obscure, even when working with one of his most potent ensembles. However, the reasons for this aren’t entirely foreign – it is a fascinating relic and something that really functions as more of a novelty for Fassbinder completists, rather than a film that stands on its own merits. Nonetheless, Women in New York is one of the director’s most fascinating experiments and certainly doesn’t disappoint if you’re in search of the raw ambition the director peddled consistently throughout his short but prolific career.

Women in New York is almost a word-for-word adaptation of Luce’s play, only translated into German. The character names and their locations remain entirely the same as the original, as indicated by the title. This already creates quite a potent, intentional alienation of the viewer, who is thrust into a story that feels remarkably detached of any particular place or time, and instead exists as an insular exploration of some concepts that were relevant in every era in which this story was told. Part of this is due to Women in New York being a filmed adaptation of a stage production that Fassbinder directed, which forms a fascinating contrast between the idea of the original text being kept intact, and the artistic licence that the director almost always employed, regardless of the material he was working with. Naturally, this story is one very much suited to Fassbinder, and begged for a more involved adaptation, rather than just filming the play. However, even taken for what it is, Women in New York is quite compelling for a number of reasons – the performances are impeccable, the production design is bizarre but oddly endearing, and the general tone that the director brings to the story, infusing his own bewildering sense of humour with the screwball qualities inherent to the original story, creates quite a polarizing, but extraordinarily unique film that may be somewhat of a chore in some parts (running about a half-hour longer than it should’ve, especially considering how this was a direct adaptation, which isn’t always optimal for the process of translating a work from the stage to the screen, with the necessary elisions not being considered in the production of the film), but finds general ease that could only come from a director who is as self-assured and in control as Fassbinder, who makes another remarkably different film about issues many of his contemporaries never quite saw the value in representing.

It seems that even within the confines of simply recording his stage interpretation, Fassbinder was providing some fascinating insights into the storytelling process with this film, resulting in quite a strange experience that isn’t always particularly successful in the more traditional aspects of the story but somehow manages to be remarkably successful on its own in terms of the more subversive aspects of the translation to the screen. This starts with the use of the camera – it stays relatively static, only occasionally pivoting across a horizontal exist, capturing anything that just happens to be in its path, whether it is supposed to be there or not. The infrequency of the camera movement, coupled with the occasional use of zoom or dollying across the stage, creates quite a puzzling sensation, giving Women in New York the appearance of being a voyeuristic journey into the lives of the women it is representing, with the camera remaining static, and the performers themselves navigating the space afforded to them. The audience becomes somewhat involved in the story, being complacent viewers launched into the private bathrooms and boudoirs of these characters, watching the events unfold slowly and gradually, with the camera always being hostile to the encroaching despair that underpins this story, and is used as a central narrative hinge for the film as a whole. Its a disconcerting experience, and somehow manages to be poignant without any of the sentimentality or heartfulness that Fassbinder normally employs in his films. It isn’t an approach that was inherently going to be successful – the honest truth about Women in New York is that its one of the films Fassbinder produced rapidly for television broadcast, with minimal effort being put into it – the difference is that it managed to be quite successful, even without the hard work normally put into the director’s work.

Women in New York is quite a compelling film, even when it is at its most unsettling – a large part of this is due to the director’s prowess in deriving some remarkable performances from his cast. As mentioned before, Fassbinder was one of the most distinctive directors of female performances – while some of the roles may be considered exploitative, the majority of his career was defined by strong roles for women. As a result, he assembled a terrific posse of actresses, all of which did some of their best work under his direction. Women in New York employs two of his most notable collaborators – Barbara Sukowa plays the role of Crystal Allen, the seductive young woman who serves as the film’s primary antagonist and eventual tragic hero, bringing an exuberance to a role that benefits from her unique youthfulness that carries an immense amount of heft that isn’t made clear until the film calibrates and focuses on her, which is when it truly flourishes. Margit Carstensen is a riot as the elegantly insidious Sylvia, who acts as a sadistic officiant of the Upper West Side drama, an omnipotent presence that encourages a form of societal chaos while remaining relatively free of any obligations. Carstensen is a marvellous actress, and while she has flourished in more empathetic roles, to see her play a villainous character, without necessarily crossing the moral boundary that she flirts with consistently, she’s able to give a very memorable performance that overcomes some of the film’s more troublesome material. Veteran actress Christa Berndl, in her only collaboration with Fassbinder, rounds out the leading roles as Sarah, the over-the-top divorcee who loses everything but still manages to come out on top as a result of her resilience. The ensemble of Women in New York, whether a major role or simply a minor character, are exceptionally strong, and demonstrate Fassbinder’s deft ability to derive fascinating performances, even when his ideas and their execution aren’t as effective as he seems to think they are.

It’s undeniable that Women in New York is a minor work from Fassbinder, and it really can only be appreciated by those who are interested in every aspect of the director’s style – it certainly is amongst his more inaccessible works, mainly considered his approach to the story, which is in itself a very faithful adaptation, is quite bewildering – the production design alone is something to behold, with the strange use of space being one of the film’s most indelible aspects, with the sets looking as if they come from another world entirely. However, below the oddity that pervades the exterior of the film, Women in New York is a very fun film – while it is certainly one of Fassbinder’s purest comedies, it doesn’t lack the fascinating commentary he frequently employed throughout his career. It’s not the easiest film to watch, based on the style and the fact that the viewer is always kept at a distance, an unfortunate by-product of Women in New York being a filmed version of the play, yet it is still remarkably interesting as a relic, an underseen component of one of cinema’s most prolific careers. It’s not always successful, but it is at least consistently interesting, and even if we put aside the strange choices Fassbinder makes, there’s very little doubt that much of the raw brilliance that made him one of cinema’s most enigmatic auteurs are entirely present in this puzzling anomaly of a film.