Watching Taika Waititi rise from being an unheralded director of obscure independent comedies to one of the most sought-after directors working today has been an interesting experience, especially for those of us who have been devoted to his work since the earliest days of his career (the discovery of Eagle vs Shark is still one of the most delightful moments in my journey of becoming a film fan). However, he’s often been the subject of numerous critical discussions, where his perceived decline in quality correlates almost exactly to his rise to fame, which is not all that out of the realm of possibility, particularly when we notice how he has gone from directing near-perfect comedies such as What We Do in the Shadows, to being yet another great director ensnared into the Marvel Cinematic Universe (despite his entry being one of the strongest films produced by the studio). However, between these two polarities is Jojo Rabbit, a film that doesn’t quite align with either, but exists as its own insular set of ideas, funnelled into a form that is very much on-brand for what we’d expect from a director who has often looked into the human condition from the perspective of a child protagonist (and to great success with Boy and Hunt for the Wilderpeople being terrific coming-of-age comedies), but still ambitious enough to qualify as being yet another attempt by Waititi to expand on his bizarre but nonetheless interesting view of the world, taking on a quite a challenging story, while employing some of his signature style to the more sinister thematic underpinnings. Jojo Rabbit had an enormous set of challenges to overcome, and while we can rhapsodize on how it could occasionally be misguided, but is nonetheless just as compelling as we’d hope, and perhaps even more so. It’s a film that has more interesting ideas than it knows what to do with, which is perhaps both the most significant shortcoming and area in which the film showed the most promise that wasn’t always met in the way the director has made evident in the past.

Watching Taika Waititi rise from being an unheralded director of obscure independent comedies to one of the most sought-after directors working today has been an interesting experience, especially for those of us who have been devoted to his work since the earliest days of his career (the discovery of Eagle vs Shark is still one of the most delightful moments in my journey of becoming a film fan). However, he’s often been the subject of numerous critical discussions, where his perceived decline in quality correlates almost exactly to his rise to fame, which is not all that out of the realm of possibility, particularly when we notice how he has gone from directing near-perfect comedies such as What We Do in the Shadows, to being yet another great director ensnared into the Marvel Cinematic Universe (despite his entry being one of the strongest films produced by the studio). However, between these two polarities is Jojo Rabbit, a film that doesn’t quite align with either, but exists as its own insular set of ideas, funnelled into a form that is very much on-brand for what we’d expect from a director who has often looked into the human condition from the perspective of a child protagonist (and to great success with Boy and Hunt for the Wilderpeople being terrific coming-of-age comedies), but still ambitious enough to qualify as being yet another attempt by Waititi to expand on his bizarre but nonetheless interesting view of the world, taking on a quite a challenging story, while employing some of his signature style to the more sinister thematic underpinnings. Jojo Rabbit had an enormous set of challenges to overcome, and while we can rhapsodize on how it could occasionally be misguided, but is nonetheless just as compelling as we’d hope, and perhaps even more so. It’s a film that has more interesting ideas than it knows what to do with, which is perhaps both the most significant shortcoming and area in which the film showed the most promise that wasn’t always met in the way the director has made evident in the past.

Jojo Rabbit was not a film that could’ve been particularly easy to put together, mainly due to the fact that the two most pivotal aspects of the filmmaking process – the message and the execution – were not all that compatible in theory. Envisioning a film about Nazism, but making it as a bold, childlike comedy was an enormous risk, and something that the film, while still quite successful, struggled to do with the ease it clearly intended. Waititi is clearly sampling from some of his comedic forebearers in how he handles this material, with broad overtures of the likes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus and Blackadder being present throughout in how the director evokes the absurdity, with the influence of the twee works of someone like Wes Anderson (who is often referred to in discussions about this film, whether as a merit of a flaw) giving it a certain sentimental exuberance that Waititi hasn’t always been able to demonstrate, but which he is attempting to make very clear here. However, this is precisely where the film slightly starts to come apart at the seams, as it seems to inundated with infusing bold, fearless humour in its approach to what is undeniably a very dark story, it loses itself along the way – perhaps not enough to render it incompetent, or distract from the more charming aspects of it, but certainly significantly to never allow it to reach the impossibly high standard it set for itself. Jojo Rabbit is not in any way a bad film, but rather one that can be called tonally misguided, and far too overstuffed with various ideas that don’t always come together in the way it seemed to think it was capable of. Waititi seemed to unfortunately be taking on far too many concepts than he could put into a single film, and the result is something that doesn’t always work.

Ultimately, this is only a minor flaw of the film (and perhaps one of the only evident shortcomings, with everything else requiring a bit more thought to understand where the film went wrong), and when you set aside the small irritations that come about as a result of the film slacking in some areas and focus more on the many interesting aspects that Waititi brings to the film, you can see how delightful Jojo Rabbit actually could’ve been, and how it did ultimately pale slightly in comparison to the potential. One element that is almost undeniable is that this is not a derivative film – while it may be stylistically similar to certain works, and features a very peculiar sense of humour that has been seen many times before, the film is quite original insofar as it looks at a subject that has been the topic of countless works, and somehow manages to find an original angle. Part of this is due to the coming-of-age narrative that the director brings to the film – like he did with some of his previous work, Waititi looks at a certain social concept through the eyes of an innocent child, who it doesn’t necessarily let off the hook in regards to his more questionable beliefs (the film could have so easily made Jojo a lovable scamp whose opinions were simply cited as being the folly of youth, rather than actively engaging with them), and perceives a tumultuous time and the horrifying events that took place from the perspective of someone young and impressionable, which adds a certain gravitas to a theme we’ve seen countless times before. There is a sub-genre of films that look at the Holocaust through child protagonists, with many artists finding that the juxtaposition of childhood innocence and the atrocities of war can actually make for quite an impactful contrast. Naturally, Jojo Rabbit joins these ranks and even though it may not be a towering masterpiece, it still manages to convey a very important message that allows the film to overcome some of its more notable flaws, even if its only for a brief moment, where the self-indulgence temporarily subsides.

Humour is a tool that isn’t only used to entertain but also to educate and invoke discussions. Waititi marketed Jojo Rabbit as “an anti-hate satire”, and while this may already set this film up for the idea of overt sentimentality, its important to consider the actual boundaries it establishes in regards to how it makes use of its comedic tone. Based on the premise, and what we’ve come to see from the director on occasion in some of his more outrageous works, you’d be lead to believe that Waititi was going to make yet another bold comedy that skips over serious discussions, instead honing in on the inherent absurdity that he believes underpins the subject. Partially, this is absolutely true – how else can we justify a film that presents a cartoonish version of Hitler as the titular character’s best friend? However, those who deride this film may have been too harsh, because while their concerns are valid in terms of the tonal imbalance and the occasionally insufferable approach to the source material (which is far more serious than this adaptation), one element that Waititi gets absolutely right is the comedy. Jojo Rabbit is surprisingly a very compassionate film, which isn’t expected from an exuberant comedy set during the Nazi regime. We can easily look into the importance of satire as a social tool, but that would be going too deep into something that this film only touches on, but does so in a very convincing way. Jojo Rabbit is made up of contradictions – for every moment of ludicrous comedy, there’s one of profoundly moving pathos, and through the intersections of two seemingly irreconcilable issues, the film manages to become a buoyant, joyful experience that seems content to settle for the bare minimum, but still manages to find some incredible warmth, giving it a familiarity that may not be all that exciting, but is certainly quite unique for a film that treading such potentially perilous narrative territory, making it an unexpectedly potent satire.

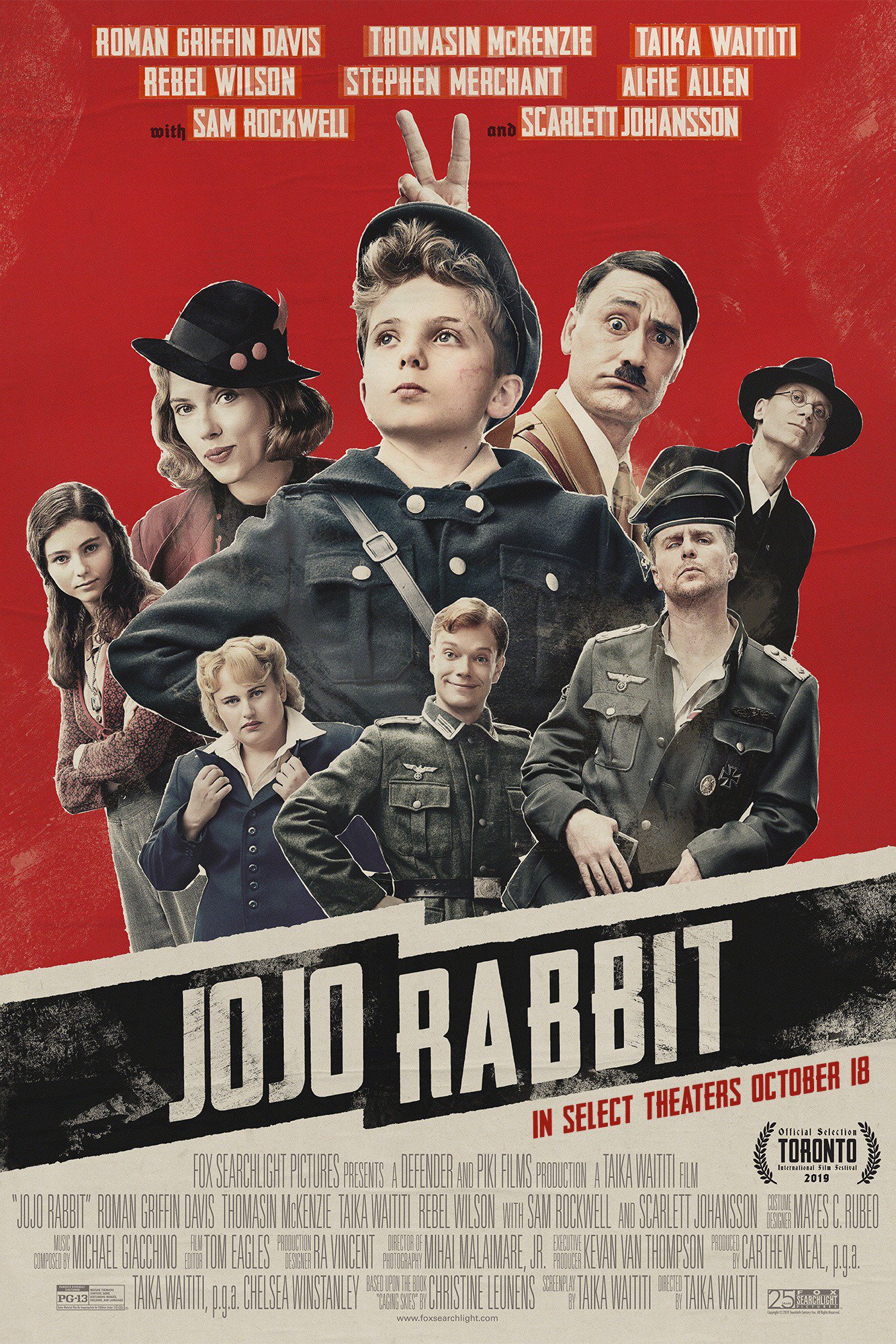

Jojo Rabbit is understandably a film that caused something of a stir, and not without reason. Making a film of this nature is always going to come with some doubts on the half of any logical audience member, who should naturally be averse to the idea of a film that deconstructs a harrowing historical event and presents it as a series of quirky situations, channelled through a set of eccentric characters who are not much more than thin archetypes designed to shepherd this story forward without having too meaningful a discussion around the subject matter and the message it conveys. Jojo Rabbit is by no means a subtle film – but it didn’t really need to be since it was designed for a specific subset of the filmgoing population that tends to enjoy this brand of exuberant comedy. However, Waititi contrasts the schmaltz with a certain elements that make it quite successful – the performances are great, with Roman Griffin Davies being a true revelation, and Thomas McKenzie proving herself to be one of the most interesting young actresses working today, and a supporting cast composed of scene-stealing character actors (Sam Rockwell, in particular, is a lot of fun, as is Rebel Wilson, whose bombastic personality works very well in terms of what this film was going for) creating a memorable set of individuals that aren’t much more than caricatures, but are still thoroughly entertaining. There are some stark scenes that pervade the film and give it some nuance, such as the heartbreaking moment where the titular character discovers that his mother has been punished for her rebelliousness, or the poignant final moments set to a German-language version of David Bowie’s “Heroes”, that reminds us that this film has a serious message underlying the broad comedy. Jojo Rabbit may have its problems, and it sometimes struggles to navigate out of the self-imposed rut it finds itself in, but it is ultimately worth more than its outward appearance would lead you to believe, perhaps a product of the intention being far more interesting than the execution ever could have been. Its has its moments of charm and manages to consist of some funny sequences and a sentimentality that doesn’t say much, but says enough to be an adequately entertaining work of modern satire that isn’t as sharp as it could’ve been but is still relatively worthwhile, based on the very important message lurking beneath it. There was a great movie somewhere in here, it just didn’t manifest beyond a few brief moments where the more obtuse aspects subside, which is far too rare.