A young donkey is adopted by a rural French family, intended to be a lovable companion to the children as they pass their days on their farm. Their new pet is named Balthazar, and he is the subject of much adoration from the doting children, who treat him as if he were another member of their family. However, a tragedy drives the family away from their home, and they’re forced to leave Balthazar behind. He’s lovingly cared for by Marie, the daughter of the schoolteacher who takes control of the farm, even when it becomes clear that Balthazar is not as useful as he was before. Over the next few years, he is shifted between owners, all of which intend to use him for different purposes – some treat him with love, caring for him and ensuring his health and safety, as another living creature. Others (and unfortunately, the vast majority) look at him as nothing more than a tool for their own economic gain, callously exploiting him, especially when he begins to show signs of ageing, not being able to walk as fast as he did before or carry as heavy a load as they believe he should. Passed from owner to owner, Balthazar is abused, maltreated and forced into perilous situations by individuals who apparently do not value his life over their own (often illegal or immoral activities). Somehow, he always makes his way back to the now-adult Marie, who still holds a special connection with Balthazar, even though she has flourished into a young woman in her own right, who is also undergoing the same kind of harsh treatment by those around her, who use her as a means to acquire some kind of satiation. Over time, Balthazar and Marie find themselves drifting apart and eventually coming back together, somehow overcoming the challenges that are wrought on them by the troublesome people they encounter.

A young donkey is adopted by a rural French family, intended to be a lovable companion to the children as they pass their days on their farm. Their new pet is named Balthazar, and he is the subject of much adoration from the doting children, who treat him as if he were another member of their family. However, a tragedy drives the family away from their home, and they’re forced to leave Balthazar behind. He’s lovingly cared for by Marie, the daughter of the schoolteacher who takes control of the farm, even when it becomes clear that Balthazar is not as useful as he was before. Over the next few years, he is shifted between owners, all of which intend to use him for different purposes – some treat him with love, caring for him and ensuring his health and safety, as another living creature. Others (and unfortunately, the vast majority) look at him as nothing more than a tool for their own economic gain, callously exploiting him, especially when he begins to show signs of ageing, not being able to walk as fast as he did before or carry as heavy a load as they believe he should. Passed from owner to owner, Balthazar is abused, maltreated and forced into perilous situations by individuals who apparently do not value his life over their own (often illegal or immoral activities). Somehow, he always makes his way back to the now-adult Marie, who still holds a special connection with Balthazar, even though she has flourished into a young woman in her own right, who is also undergoing the same kind of harsh treatment by those around her, who use her as a means to acquire some kind of satiation. Over time, Balthazar and Marie find themselves drifting apart and eventually coming back together, somehow overcoming the challenges that are wrought on them by the troublesome people they encounter.

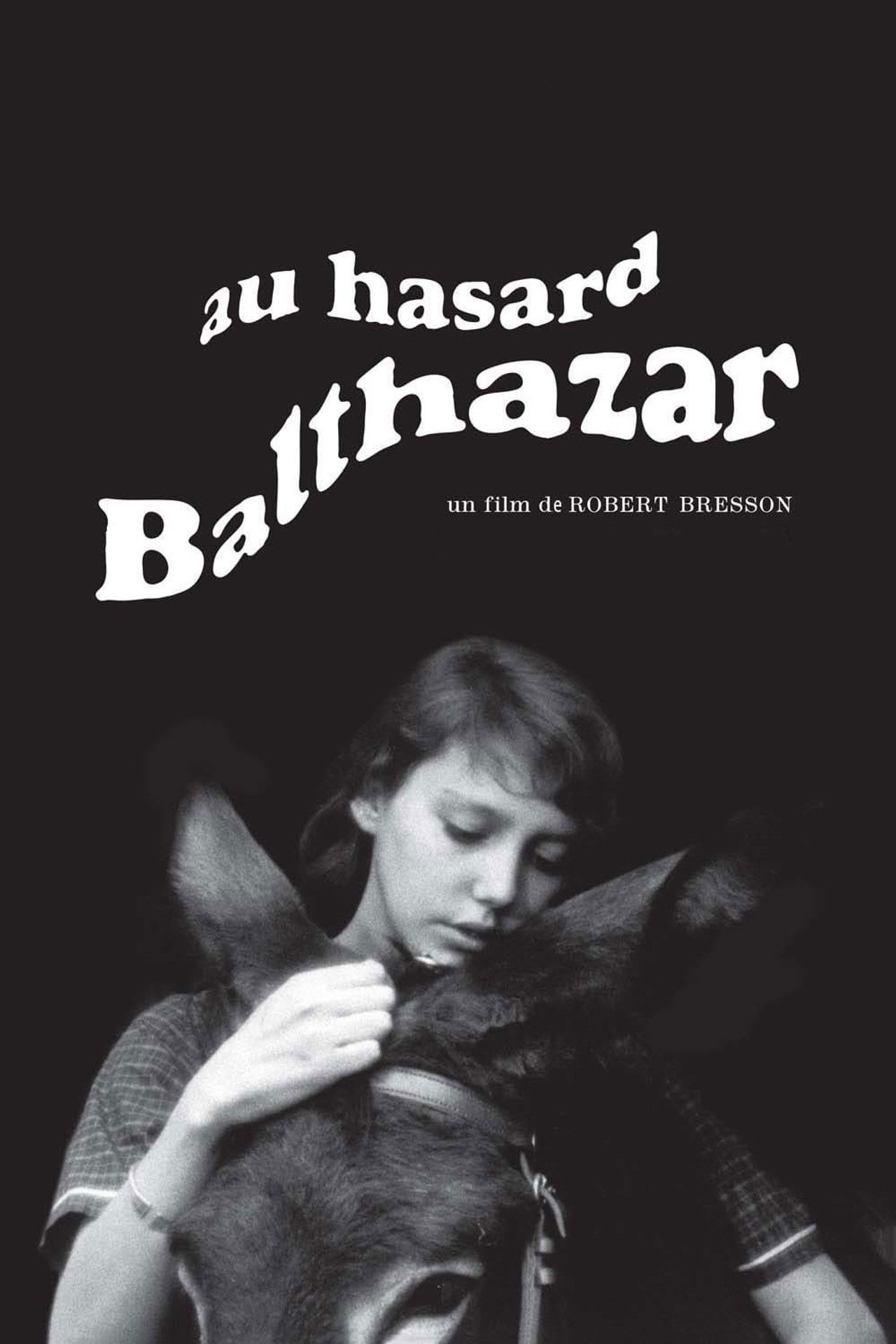

The adoration for Au Hasard Balthazar is truly one of the most fascinating in arthouse cinema. Inarguably Robert Bresson’s most beloved masterpiece, the film has risen to become one of cinema’s greatest achievements, a complex ode to existence told through the lens of a very unconventional protagonist. The challenge that comes with talking about any enormously famous film is that so much has already been said about it since its release, with the film inspiring countless essays, discussions and manifestos from a variety of industry folk, critics and members of the general public professing their love for it. However, unlike quite a few classics that are revisited half a century since their release, Au Hasard Balthazar still stands as an enormously impressive achievement, a beautifully poetic film that takes an extraordinarily simple approach to some deeply complex ideas, channelling profound commentary through the guise of, to quote what many have used to refer to this film as, “the life and death of a donkey” – and only someone with the skilled directorial vision and sheer ambition that Bresson demonstrated throughout his iconoclastic career could ever hope to evoke with such immense heartfulness and spirit, telling the haunting story of life and its challenges through the most authentic filmmaking possible. Bresson truly set the standard for realist cinema throughout his astonishing career, but Au Hasard Balthazar will always be remembered as the most profound of his works, a gentle and allegorical drama that looks deep into the soul of its characters and questions their humanity by confronting them with issues of their own individual existences. It’s beautiful, poetic cinema that remains one of the most fascinating insights into reality ever committed to film.

Bresson was a director whose work always seemed to be intent on encapsulating life and its many different challenges, with each of his films normally taking aim at one particular theme and seeing it through to the end, exploring that one specific aspect of human existence with precision and meticulous curation of so many evocative concepts that underpin a beautifully simple story. Realism is a literary movement that is more heavily investigated in the literary format, and only tends to be widely discussed in film when it comes to Italian Neo-Realism and kitchen-sink realism, which occur on both sides of Au Hasard Balthazar, which presents a very different kind of authenticity that is missing from either of the other two major pinnacles of cinematic realism, as well as blending some of the more notable tenets – the despair of the former and the anger of the latter amalgamate into the disquieting voyage into the life of a donkey, and the different challenges he encounters as he embarks on a metaphysical journey that sees him becoming the folly of several individuals who value themselves over his own wellbeing. Taking his cue from the great Victorian realists, who often composed their greatest works amongst the pastoral European landscapes, Bresson restricts this story to a small rural region of France, an intentional choice that not only prevents this film from being situated in a particular temporal moment (and thus making it resonant to any period and context it is watched it), but also gives it a certain simplicity that is not often found in more notable audacious realist works, which normally prioritize the idea of urbanity impinging on the simplicity of nature, which is contended in Au Hasard Balthazar, which demonstrates a very different side of such discussions, without ever needing to preach or become overly sentimental, but rather remaining starkly real.

To quote Jean-Luc Godard, Au Hasard Balthazar is “the world in an hour and a half” – every piece of writing about this film seems to contain some variation on this thought, which is certainly a very adequate way to represent exactly what Bresson was trying to achieve with this film. The key to understanding precisely what it is that makes Au Hasard Balthazar so compelling is not by remarking that its a great film – this is a pretty universal fact that has become almost indelible in the culture – but rather to describe exactly what it is that makes it such an enduring masterpiece. Like many of the great realist texts in the past, Au Hasard Balthazar is singularly uninterested in moral grandstanding or lavish exuberance, to the point where it becomes clear that the lack of style was actually a subversive attempt to create a distinct atmosphere, which Bresson evokes with such enormous sincerity and honesty. It is a film that carried radically different interpretations for each viewer, so to provide a catch-all summary of what it achieves is almost impossible, particularly because, much like life itself, you can’t discern a particular universal meaning from this story – each one of us will latch onto something different, whether it be the moral underpinnings, the social issues that the director brings up, or the more abstract concepts of faith. However, what is certainly almost undeniable about Au Hasard Balthazar is how it is universally resonant in some way since it attempts to distil life into a single coherent thread, and through his immense creative genius, Bresson manages to do just that, and with truly compelling results.

In using a donkey as the protagonist of Au Hasard Balthazar, Bresson calibrates his focus away from the humans (who are ultimately peripheral to the film, with the exception of INSERT NAME, who is truly impressive as the young woman grappling with her own humanity), and instead gives us a glimpse into existence from something of an exterior perspective – by no means the gaudy “animal film” that anthropomorphizes a beast as a means of comedic relief or darkly twisted satire, but rather a more elegant approach to questioning deeper issues by looking at human behaviour when asserted onto an innocent creature like the titular Balthazar. Unquestionably one of cinema’s most tragic protagonists, the donkey is a vessel for humanity and its various man-made injustices, serving as something of an allegory. There comes a point when everyone first hears about Au Hasard Balthazar, with the idea of an extremely serious film centred around the life of a donkey seeming somewhat absurd – but the experience of seeing what Bresson does with this motif is absolutely spellbinding, with the director removing all sense of novelty from the premise, and replacing it with inextricable humanity. Its often a very difficult film to watch – Balthazar is treated so poorly, and receives very little in exchange for a lifetime of hard work that always resorts to outright abuse, with the ending being one of the most harrowing in the history of cinema. Yet, despite not infusing this film with anything close to traditional comfort, Bresson’s approach is one of genuine compassion – his intention is what propels this film forward. He was certainly not limiting himself to the trials and tribulations of a donkey, but rather using it in a very creative way to give insights into wider human tendencies.

Many other people who have been touched by this film have provided in-depth analyses to the film, where socio-cultural context, religious allegory and other meaningful discussions are had. The film touches on many raw subjects and has inspired generations of artists to explore humanity from wildly different perspectives, often resulting in some of the most powerful films ever committed to the screen. Ultimately, its the simplicity of Au Hasard Balthazar that makes it so worthwhile – Bresson was a director whose work was stark and unfurnished and often hinged on a sense of minimalism to convey their message. This was certainly the best approach for his style, as he managed to make some profoundly moving comments without resorting to excess, which would clash with his effectively straightforward style. In Au Hasard Balthazar, the director lays everything bare and tells a story without any sense of needing to lead the audience in one particular direction. Its something of an objective demonstration of a small portion of humanity and the responsibility is on the audience to interpret and extrapolate meaning, which normally comes from within, as they engage with the bold imagery they’re presented with. Au Hasard Balthazar is a truly gorgeous film, not only for the story it tells but the emotions it evokes. It’s simple, beautifully honest and unimpeachably human, and when taken from the perspective of an artist whose primary intention throughout his career was to find some deeper meaning to reality, it’s impossible to not see Au Hasard Balthazar as a resounding success, and quite simply one of the most important films ever made, both for what it did, and what it would inspire others to do.