“There are monsters who act like people, and people who act like monsters”

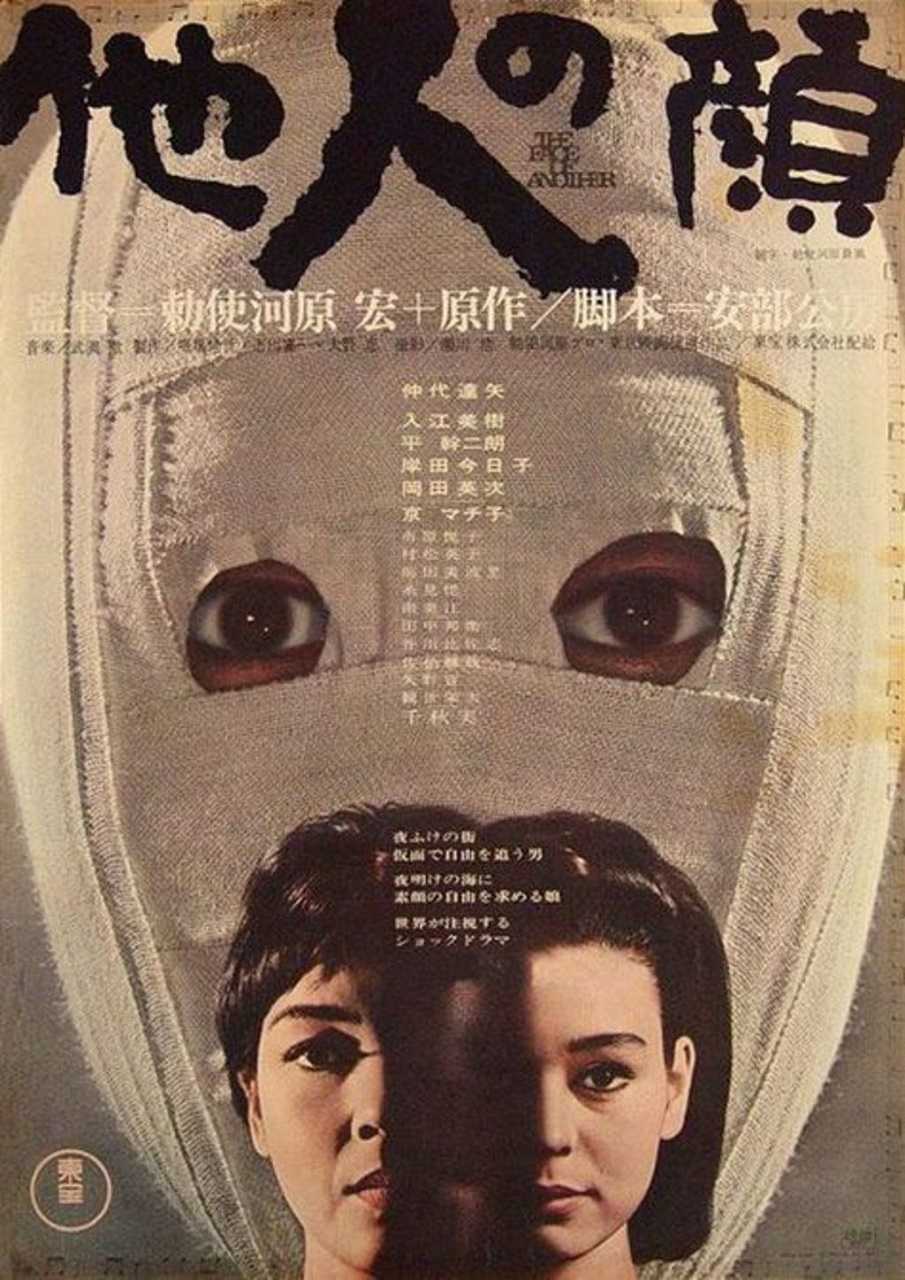

The Japanese New Wave brought attention to many fantastic filmmakers who were afforded the opportunity to tell their subversive stories through venturing beyond the confines of what many of their more formalist (but no less influential) compatriot forerunners had defined as being the true essence of cinema. One of the artists who emerged during this period was Hiroshi Teshigahara, who made several incredibly important films that characterized this alternative period in Japanese cinema and confirmed Teshigahara as one of the most enduring postmodern filmmakers of his era, in a time when such a term wasn’t even acknowledged, let alone widely used. One of his defining works was The Face of Another (Japanese: 他人の顔), a daring look into the human condition from a fundamentally unique perspective. Traversing the boundary between nihilistic dark comedy and bizarre body horror, Teshigahara engages us in a journey of immensely bewildering proportions, presenting us with a subversively poetic film about the limits of identity and how he negotiate our place in the world, channelling these themes through a poignant, but deeply unsettling, story of a man who has lost his face, and by extent has become unrecognizable, both physically and in terms of the more abstract elements of his personality – all realized by the incredible work done by Tatsuya Nakadai, one of the finest actors of his generation. Strange in its premise and execution but potent in both its style and thematic underpinnings, what Teshigahara does with The Face of Another is an unprecedented move towards a form of darkly satirical social commentary that doesn’t need to satiate any preconceived standards of filmmaking, but is rather formed from an intrepid liberation from expectations, creating a truly unforgettable, and frequently disconcerting, foray into the collective mentality of society and its often unsettling cultural standards.

An unfortunate accident leaves successful businessman Okuyama (Tatsuya Nakadai) with burns so severe, he is forced to cover his facial scars with layers of bandages, as the damage to his appearance was far too immense for him to have any hopes of recovery. His insecurity prevents him from overcoming this physical problem, and even when he is offered the exact same quality of life, whether it be the adoration from his wife (Machiko Kyō) who asserts that she doesn’t care about his appearance, or his employer (Eiji Okada), who tries to convince him to go back to work, he refuses and finds himself stricken with despair that he has never experienced before. His only solace comes in the form of the psychiatrist assigned to treat Okuyama, Dr Hira (Mikijirō Hira), who also secretly dabbles in other forms of science, particularly those relating to body parts. Upon hearing of his patient’s insecurity and inability to lead a normal life due to the challenges of overcoming such an enormous challenge, Hira arranges for Okuyama to be his first subject in a very experimental procedure – a mask would be made (designed after a local man volunteers to be the model), which would give Okuyama the chance to lead a normal life, albeit only temporarily, as the mask could not be worn permanently. However, he takes the opportunity not to return to his life before the accident, but to rather form a new one – and renting an apartment in the city, he embarks on a reinvention, adopting a new persona, with the intention of fooling those around him into believing that he was someone else. This manifests in his twisted plan to seduce his own wife and coerce her into engaging in an affair with him, to test her loyalty. However, Hira warns Okuyama that the mask could very easily take over, and the repercussions that come with taking on an entirely new personality could be far too perilous for him to handle. Yet, being afforded the chance of a new life is not something that Okuyama thinks too thoroughly about, and he finds himself in a situation that is far worse than where he was before, with no chance of escape, as he’s no longer battling for acceptance from society, but rather from himself.

The Face of Another is a film that follows quite a simple premise, with the complexity coming in how it ventures beyond the confines of the specific story and presents us with a deeper commentary, evoked by the relationship the film has with its subject matter, which only becomes clear midway through the film. Teshigahara succeeded in doing what many filmmakers attempt but don’t always get quite right – to tell a potent story about the fundamentals of being human, delving deep into the nature of existence, and extracting powerful commentary on the intrinsic qualities that either bind us together or draw us apart, based on how we handle the innumerable challenges that are often worsened by social perceptions that can impinge upon progress in some way. The film is insistent on searching for the humanity in a very hellish urban landscape, where Teshigahara makes use of a deep sense of existential dread in his darkly comical indictment on human perception and our relationship with our surroundings, particularly in a nation that is still very much in recovery from the immense damage from the war, recovering from both cultural and psychological wounds. Aligned in many ways to the urban uncanny archetype of the Modernist philosophy and how the angst and despair from changing mentalities around this period, and which was mostly utilized during the era of silent cinema, being most prominent in the works of the notable German Expressionists, The Face of Another situates us in a deceptive landscape that appears to be navigable, but through the eyes of a troubled protagonist, it becomes a challenge, particularly in how he is forced to reevaluate his place in a society that has inadvertently distanced itself from him, by virtue of his appearance, which doesn’t meet the basic criteria of normality, which is what causes him to seek out alternative methods of assimilating back into society, as a complete individual, rather than a horrifying novelty that is either feared of the subject of abstract fascination.

The Face of Another contains an immense amount of metafictional commentary, particularly in regards to the sub-plot of a similarly-scarred woman and her path towards psychological self-destruction, which contrasts the main storyline and dovetails into a fascinating indictment on society’s tendency to assert stringent standards on what they consider to not only be normal but also acceptable. Identity is an inherent aspect of the human condition and is often an area in which many of the most socially-conscious artists tend to focus, particularly when looking at a protagonist who has been made a social outcast, solely a result of their failure to adhere to some socially-conditioned standard. Where The Face of Another differs considerably is that this is not a film made as a morality tale – the director is remarkably earnest in his decision to infuse an enormous amount of bleak cultural commentary throughout the film, avoiding the pratfalls of preaching by demonstrating a keen sense of provocative brilliance, both in the narrative themes he’s exploring, and the fascinating ways it manifests. Identity is fundamental to how we negotiate our place in the world, but instead of presenting us with a character that we’re made to feel pity for, due to his accident, Teshigahara instead gives us a despicable man, whose tragic plight is contradicted by his arrogance and belief that he’s been the victim of a cruel society when in actuality, he’s the only one who sees his disability as being limiting. The film incites a discussion on the construction of identity – are we truly free to choose who we are, or are we simply the results of generations of cultural-conditioning that has slowly shaped us into the individuals we have become? Moreover, it questions whether identity is indelible, or if it can be more malleable – we can change our name and our appearance, but when it comes to more internal aspects, such as those of the soul, are we truly in control? Teshigahara goes to great lengths to look at these deep questions while still noting how he doesn’t intend to resolve them – these are enormous quandaries that have been the subject of rumination for as long as we’ve been self-aware, and The Face of Another brilliantly takes these themes and subverts them in a truly mesmerizing manner.

Like many postmodern works, The Face of Another is a film that is built on the foundation of nothing being what it seems, looking into the literary trope of appearance in opposition reality, and the way the protagonist (or could we consider Okuyama an anti-hero?) perceives the world around him. Teshigahara approaches this film from an internal perspective, quite literally looking at the message through the eyes of the main character, as he treads the perilous social territory while being the antithesis of what he believes to be acceptable. The film is notably lacking in judgment – nearly every character who interacts with Okuyama in his more vulnerable state are friendly and understanding, which is sharply contrasted with their hostility when he adopts a more traditional appearance. The film subverts the cliched message of society being unfair to an outsider by demonstrating a keen sense of irony in positioning the main character as someone looking to be made a social outcast, as he’d much rather stand out than fit in, as it suits his carnal desire for sympathy. He experiences a form of isolation that is entirely his own doing – and without going too deep into his psychological machinations, Teshigahara conveys a disconcerting attitude towards his attitude, and evokes questions of ugliness, which is ultimately the main focus of the film. The Face of Another is a film about hideousness, but not the kind that is normally the subject of these stories. Its not Okuyama’s scars that make him an outsider, but rather the fact that he carries a damaged soul. He’s broken, insecure and hostile to the world around him. He believes others are implicit in destroying his life and rendering him mediocre, when it actuality, its his own complacency that causes this immense alienation. He is warned that the mask will eventually take over if he’s not cautious – this word of warning is not rooted in the idea that his disguise will become sentient, but rather give him the chance to explore his own arrogance, to the point where his inner state of being a hubristic, morally-corrupt hedonist will surface. He blames this on the mask when in actuality, its the arrogance that comes with being able to fit into a society that he’s been running from that does it for him.

The Face of Another is a tremendously interesting film, one that operates as both an impressive directorial achievement, and a deeply unsettling social manifesto that evokes discussions that challenge the very notion of existence, while never resorting to overwrought commentary or inappropriate flippancy, particularly in regards to the underlying comparison between physical appearance and social perception. Teshigahara crafts a chilling dark comedy that does not avoid the more bleak subject matter, particularly in the final act, in which the broad overtures of horror begin to pervade into an otherwise outrageously surreal satire. Beautifully-composed in form, with gorgeous cinematography conveying an image of the urban cityscapes of Japan and their intimidating relationship with the protagonist, and an emphasis on creating an atmosphere to contrast the unflinchingly challenging themes of alienation, the film gradually grows in intensity, until it reaches a horrifying crescendo, which is most significant in Tatsuya Nakadai’s immensely powerful performance as a man trying to regain his confidence, but inadvertently finding himself becoming his own worst enemy. The film blends humour with a very bleak storyline and leaves the viewer with innumerable indelible images, which will remain haunting long after this chaotic social masterpiece has ended. The Face of Another is one of the most quietly provocative films of its era, a fearless New Wave thriller that focuses on broad themes while never generalizing the message, creating an unquestionably powerful work of metaphysical fiction that is both an impressive film and an immensely poignant piece of commentary.