There are two ways to look at Good Times – the first is a relic of the 1960s, a time-capsule of a decade in which so much social and cultural change came about, made with the intention of simply entertaining audiences with its irreverent sense of humour and upbeat demeanour. The second is as a hopelessly dated vanity project for Sonny and Cher, made with the intention of giving this superstar couple a showcase for the work that had made them so popular – add to that it was the debut narrative feature film by William Friedkin, who would go on to be one of the most influential filmmakers of the New Hollywood era, and you have quite a bizarre work. I tend to lean towards the latter, but to invalidate the more enjoyable aspects of this would be would misguided, because even while it may be a jumbled attempt at portraying the counterculture era, and one that has not aged particularly well (especially in retrospect, where we are fully aware of where these two individuals will end up later in their career, one a controversial politician, the other one of the biggest cultural icons of her generation), there’s a certain likability that prevents Good Times from being a massive disaster. While it may frequently betray its title, the film is a relatively fun experience, a diversion that functions less as a cohesive work, and more as a remnant from a bygone era – and like many similarly-themed films, the most pleasure is derived from looking at what the film stands for, rather than what it actually says.

There are two ways to look at Good Times – the first is a relic of the 1960s, a time-capsule of a decade in which so much social and cultural change came about, made with the intention of simply entertaining audiences with its irreverent sense of humour and upbeat demeanour. The second is as a hopelessly dated vanity project for Sonny and Cher, made with the intention of giving this superstar couple a showcase for the work that had made them so popular – add to that it was the debut narrative feature film by William Friedkin, who would go on to be one of the most influential filmmakers of the New Hollywood era, and you have quite a bizarre work. I tend to lean towards the latter, but to invalidate the more enjoyable aspects of this would be would misguided, because even while it may be a jumbled attempt at portraying the counterculture era, and one that has not aged particularly well (especially in retrospect, where we are fully aware of where these two individuals will end up later in their career, one a controversial politician, the other one of the biggest cultural icons of her generation), there’s a certain likability that prevents Good Times from being a massive disaster. While it may frequently betray its title, the film is a relatively fun experience, a diversion that functions less as a cohesive work, and more as a remnant from a bygone era – and like many similarly-themed films, the most pleasure is derived from looking at what the film stands for, rather than what it actually says.

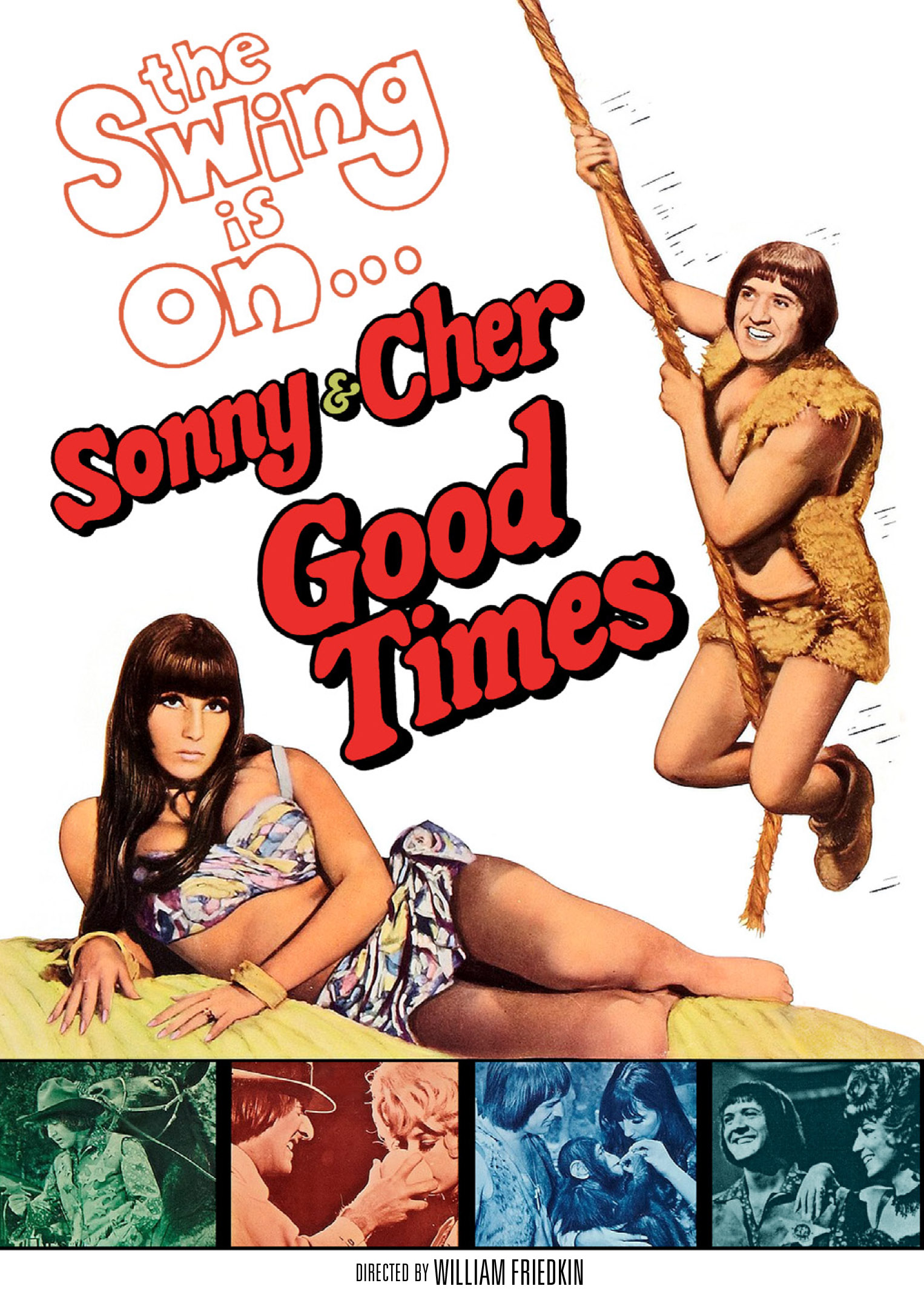

Cher and Sonny (played by Sonny and Cher) are looking to enter into the film industry when they receive an offer from Mr Mordicus (George Sanders), a film tycoon looking to capitalize on their popularity by proposing a star vehicle for them. However, the couple doesn’t realize the perils of the film industry and begin to grow disgruntled towards the scripts they are given to look through. They imagine themselves in many of these films, including a western, a jungle adventure and a film noir, only to realize that none of them are fitting, with their presence only serving to make the film profitable. Mordicus, however, is vehemently against their rebellion, forcing them into a position of subservience, reminding them of how they have been bound by a contract that ensures that they deliver a film, or else he will guarantee they will decline in the entertainment industry, with his company being so influential, he is able to destroy any career should he feel so inclined. Traversing between different genres while trying to come to a compromise, while still dealing with their own marital strife, borne from the tensions underlying their difference of opinion regarding the film industry, Sonny and Cher find themselves trying to maintain both their careers and their loving relationship, even when external forces try to destroy both of them.

Good Times is either the most brilliantly subversive satire of the 1960s, or a blatantly self-indulgent vanity project made purely for the sake of giving the studio a chance to profit by putting two of the era’s most beloved stars in a film, hoping that audiences will be compelled to see Sonny and Cher, a pair of entertainers loved for their television work, as well as their music, in a feature film. It was a gamble that could’ve paid off, or failed miserably – and we can confidently state that it turned out to be neither, as the film is a relative non-entity, to the point where it isn’t particularly revolutionary, nor is it offensively bad in any way. There are a few major issues underpinning this film, all of which go back to the fact that this is nothing more than an excuse to throw the central pair into a film for no reason other than fiduciary gain. Yet, there’s a charm that comes with Good Times, the kind that those who have a penchant for camp will truly appreciate. It’s almost admirable how bizarre this film is – conceived with the sincerity of capitalist executives, and executed with the self-awareness of a hippie on an acid trip, this film is truly something to behold – and for those who subscribe to the idea of the imperfections sometimes being the most endearing part of a film, this is certainly an example of perspective dictating how we consume a film. Frustrating, but also outrageously bewildering in both form and content, you can’t quite help but love this beautifully incompetent excuse for a film.

Before writing this review, I asked myself the question that normally comes when looking at something that is far from conventional – “where to start?”, which is both a potent question, but also one that is singularly impossible to answer, since absolutely nothing in this film seems to adhere to any logic, with the flow being truly bizarre, to the point where we find ourselves resigning to the fact that we may never quite understand Good Times and what it was trying to achieve. Arguably, a big part of this film depends on being present at the time in which it was produced, which is most likely the reason why looking at this film half a century later is quite a strange experience. Even without having been around at this point, it’s clear that simply knowing how Sonny and Cher were perceived at the time isn’t enough – one needed to be immersed in the phenomenon that was this pairing. For a studio to have put up enough money to allow this duo to have their inexperience as actors broadcast to an enormous audience could only have been motivated by the belief that people would obediently march into cinemas to see them gallivanting across the screen. The confidence emanating from Good Times is quite extraordinary, especially when we consider how the careers of the three individuals at the centre of the film, the main duo and director Friedkin, would deviate in the years following this film. If anything, we can appreciate Good Times as a brief glimpse into an era that was recent enough for us to have social and cultural context, but still too distant to rationalize exactly why anyone would think this would be a good idea. Yet, someone clearly did, which is why we have this gloriously baffling work of semi-fiction.

As a cultural relic, Good Times is infallible – there are few films that manage to capture the spirit of the 1960s quite like this. It proves every stereotype of entertainment at that time, from the lavish costumes to insincere love songs and poorly conceived romance plots, were all true. Unlike the majority of films, this was not made to carry over for future generations to enjoy – I can’t think of a single individual born after the time in which this film was made feeling the same unironic joy that comes from seeing these two actors struggle their way across a gaudy story of the cult of celebrity. To double-down on the datedness of this film, someone truly believed it would be irresistible to put Sonny Bono in the central role. The Sonny & Cher partnership was one that was clearly dominated by the former, with Cher always having to be nothing more than a highly-visible sidekick to a man who unfortunately had no discernible talent other than a charm that could persuade the most cynical viewers to adore him. This isn’t a criticism – Bono was a great entertainer, but one that came from a generation in which being present and popular was a winning formula. Placing him in the prominent position of this film, in which the entire story hinges on his character’s decision, is certainly not what we’d expect, especially when it is clear that Cher is struggling to make her mark on a film in which she is actually the better of the two. It also doesn’t help that George Sanders, one of the most acclaimed actors to come from the Golden Age of Hollywood, was given a role that is, in the most frank terms, an insult to his talents – just consider how the character he plays in one of the vignettes is named Knife McBlade, and you’ll understand how much the filmmakers valued the contribution of someone like Sanders, who was clearly hired to give some gravitas to an otherwise nonsensical example of cinematic self-indulgence.

To the modern viewer, Good Times is a perplexing work, but one that we can assert some deep analysis of the role of celebrity and how it is often a predominant aspect of mainstream artistry, whereby reputation supersedes talent. It is difficult to get a grip on what Good Times actually wants to say since the plot demonstrates how it seems well-aware of the theme of capitalizing on fame as a way to profit off unsuspecting viewers while doing exactly what it is criticizing. However, we can’t truly judge this film solely through a broad lens, since there is so much going on beneath the surface, and absolutely none of it intentional. Rather, we should just appreciate this bizarre film that dares to take us to some very strange places, both narratively and spiritually. There is some good to come out of Good Times – it reminds us of how brilliant a performer Cher actually is, not because she’s good here, but because she would eventually grow out of this pairing in which she was so ridiculously shafted to play second-fiddle to someone whose only asset appears to be his masterful charm that can convince anyone that he is talented. It also is a fascinating piece of trivia when looking at the career of William Friedkin, as very few filmmakers seem to have the chance to start their careers with something as hopelessly unhinged as this. Somehow, Good Times is more unsettling than The Exorcist, which is truly saying something. As a whole, this is a truly confounding piece of cinema – I’m not sure if its a good time or a bad time, but I know one thing for sure: for those who want beautifully deranged, illogical camp brilliance, it’s certainly not a waste of time.