A young man named David Holzman (L.M. Kit Carson) decides that he is going to make a film, he himself occupying the central role. However, instead of constructing a feasible plot and writing a script, he chooses to simply film his own life, believing that documenting his daily activities will be compelling enough, with his life as an ordinary bohemian New Yorker likely to resonate with other like-minded individuals, who exist in the same sphere of counterculture ennui that he does. However, he soon learns that reality isn’t quite like films would have him imagine – his friends and family don’t particularly embrace the idea of their every movement being documented, and the presence of the camera in their lives serves to be less of a chance for them to realize their underlying ambitions of stardom and rather becomes a burden on their lives, an unnecessary distraction from some of the more serious situations that they find themselves in. David himself starts to realize there is something flawed in his endeavour, and that perhaps making a film about his life may not have been the wisest decision, as instead of capturing the raw truth of his painfully average existence, it evokes existential questions, and begins to provoke at the very concept of the self, which is not a particularly pleasant experience for someone like the protagonist, who simply wanted to make a film where he himself is the star.

A young man named David Holzman (L.M. Kit Carson) decides that he is going to make a film, he himself occupying the central role. However, instead of constructing a feasible plot and writing a script, he chooses to simply film his own life, believing that documenting his daily activities will be compelling enough, with his life as an ordinary bohemian New Yorker likely to resonate with other like-minded individuals, who exist in the same sphere of counterculture ennui that he does. However, he soon learns that reality isn’t quite like films would have him imagine – his friends and family don’t particularly embrace the idea of their every movement being documented, and the presence of the camera in their lives serves to be less of a chance for them to realize their underlying ambitions of stardom and rather becomes a burden on their lives, an unnecessary distraction from some of the more serious situations that they find themselves in. David himself starts to realize there is something flawed in his endeavour, and that perhaps making a film about his life may not have been the wisest decision, as instead of capturing the raw truth of his painfully average existence, it evokes existential questions, and begins to provoke at the very concept of the self, which is not a particularly pleasant experience for someone like the protagonist, who simply wanted to make a film where he himself is the star.

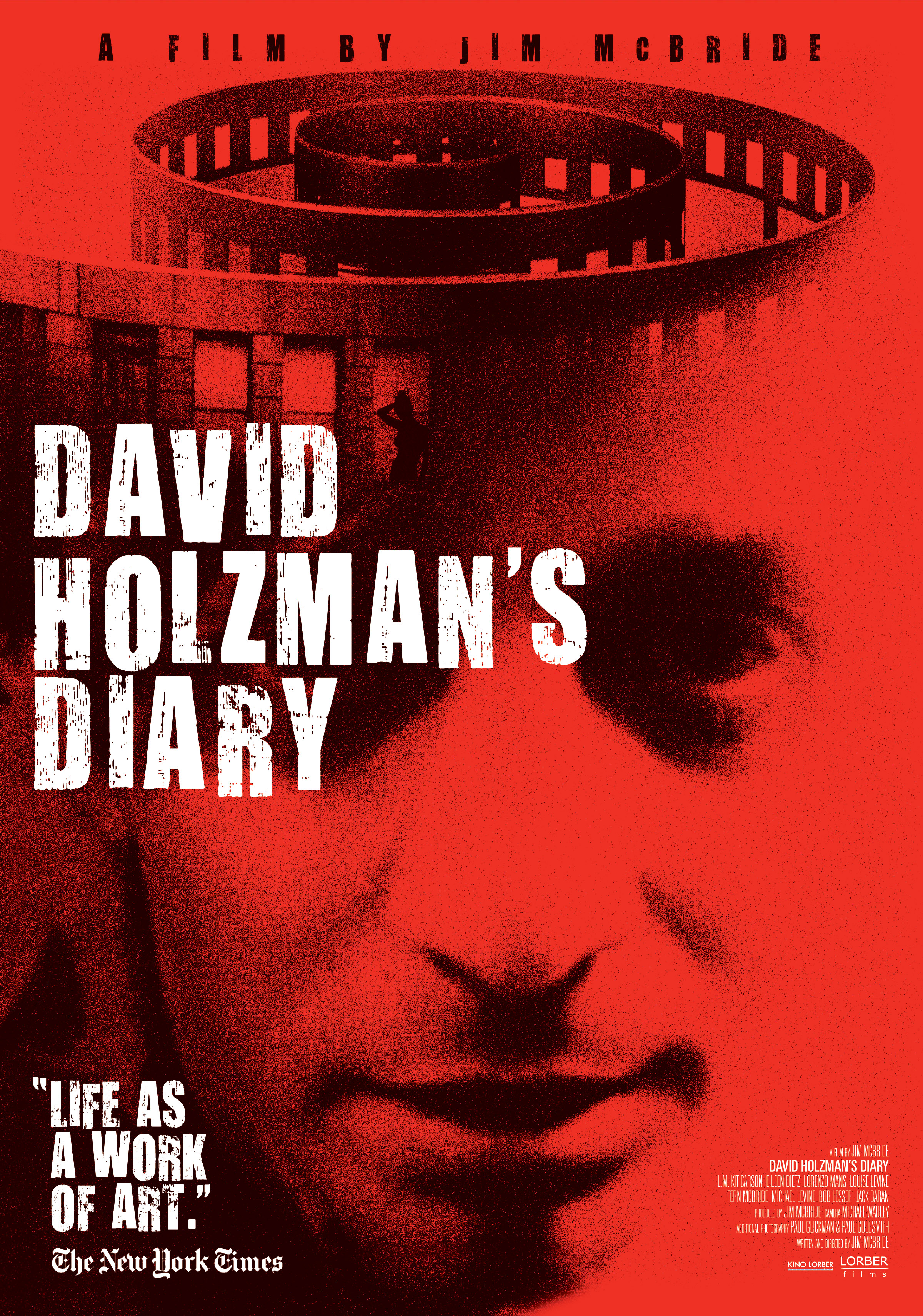

Films aren’t always a linear artform. The majority certainly are made for the purpose of telling a story or conveying a certain message, with most films venturing in similar directions in terms of their execution, only differing in certain fundamental elements such as genre, plot and purpose. However, for every straightforward film, there are a dozen experimental works, made by individuals who believed that their responsibility was to subvert the most common conventions and produce entirely different pieces that challenge the very notion of what filmmaking should me. A number of these are produced in such a way where the story itself is inconsequential, and the meaning is emphasized – there’s certainly a reason why experimental cinema, for the most part, has remained relatively niche, as the underground sensibilities of some of these filmmakers would be too out of place in a more mainstream context. However, one purpose that experimental cinema often does serve is to be an inspiration for other filmmakers, who adopt various facets of the original work and turn it into more popular entries into their respective genres. David Holzman’s Diary is a revolutionary work that inspired half a century of filmmaking, becoming so indelibly linked to so many kinds of films, it may be seen as one of the rare prototypes for a sub-genre on its own. Therefore, its relative obscurity is quite baffling – by no means a lost film, it is rather more of a relic, embraced by those interested in mid-century experimental cinema, as well as those looking deep into the genesis of independent filmmaking, where the term was not associated with trendy, alternative art, but rather a derided concept inextricably link to outsiders. However, it’s certainly quite true that David Holzman’s Diary is a terrific film that was undeniably ahead of its time.

Despite the fact that David Holzman’s Diary is not that well-known, the surprise that comes with actually seeing this film proves what a hidden gem it actually is, with the commentary produced by director Jim McBride being particularly potent in how resonant it is to modern issues, particularly those that have something to do with the artistic process. Widely considered to be the first mockumentary (I’m reluctant to abide by this rather definite statement, as a discussion on underground and experimental cinema renders the idea of an absolute impossible), this film launched a sub-genre of filmmaking that would actually only come into practice decades later, making this a film that inadvertently inspired generations of writers and directors to adopt a style of storytelling that has been shown to be embraced by both the industry and artists. However, it was clear that McBride wasn’t intended to necessarily adopt this same mindset, as there is something brewing beneath the surface of David Holzman’s Diary that indicates there’s more to this film. Like most experimental cinema, the form itself doesn’t mean much, but rather the message it is conveying, and in the case of this film, we can note with categorical certainty that everyone involved was intent on venturing beneath the veneer of the filmmaking process, to comment on the very act of commenting on cinema. Thus, this cyclical paradox brings us to the other aspect in which David Holzman’s Diary is a revolutionary piece – it is one of the defining works of metacinema.

Cinema about cinema is an area in which many filmmakers have ventured – there’s something so inherently captivating about seeing a film that is all about the process, or the effects, of movies themselves. Whether biopics of stars, or satirical comedies about the hypocrisy of the industry, filmmaking itself has received an immense amount of attention in Hollywood. What makes David Holzman’s Diary so different is that it looks beneath the veneer of the silver screen, and presents us with an intimate account of a man’s relationship with the process. We are witness to the bizarre process whereby filmmaking is reflecting on itself, provoking its own standards and sacrosanct conventions. McBride has made perhaps the most philosophical work of visual art because much like the great thinkers of the past did their best work upon looking inward, this film is looking at itself and questioning its own existence, becoming almost sentient in its composition. Certainly an absurd notion, but one that the director (both the real filmmaker and the titular amateur) seem to heavily draw on in it. Inherently postmodern in how it approaches the topic, the film is remarkably adept at tackling the very nature of artistry without being clumsy or overwrought, but instead actually finding the effervescent depth in an otherwise bewildering concept.

The very nature of filmmaking is called into question in David Holzman’s Diary, as realized towards the end, when the titular character, in a moment of uncertainty, reflects on his own intentions and simply states “I thought this would be a film about things” – and throughout the duration of this experimental masterwork, McBride, accompanied by Carson’s spirited performance as David, looks introspectively into what compels individuals to create art, especially those that are autobiographical or drawn from the artist’s own experiences. The film evokes a fascinating discussion on the boundaries between reality and fiction, which truly manifests in a poignant monologue delivered by Lorenzo Mans, playing one of the protagonist’s friends, expressing his defiance to being filmed, not because it is an invasion of his privacy, but because there is no possibility of a film ever truly being authentic. Somewhere in the ambiguous space between the subject and the lens, the truth is somehow warped – and as we see throughout the film, David’s camera purports to represent reality, but in actuality, even the most genuine attempts to convey the truth turns out to be manufactured. Even the most earnest moment is subjected to directorial scrutiny, whereby either the self-awareness of the subject or the direction of the artist, renders it slight defiant from the truth. This monologue is the centrepiece of David Holzman’s Diary and isn’t only a terrific piece of acting on the part of Mans, but a stark manifesto on the very nature of filmmaking, a haunting moment in an otherwise darkly comical film, which quietly carries a lot more heft than one would initially think.

The premise and initial introduction to David Holzman’s Diary leads the viewer to believe it would be a self-indulgent exercise, the kind of small-scale independent comedy in which the existential spirit of the French New Wave was evoked by American filmmakers hoping to replicate the same philosophical success. However, we soon discover that McBride has somehow avoided the expected pretentions, which is undoubtedly the result of his very subversive approach to some bold questions, as well as how he calibrates this film, which appeared to be going in numerous different directions, to eventually follow a single narrative thread. Surprisingly, the emphasis is put on the camera itself, with it becoming something of a character itself in the film. One of the fundamental rules of a documentary is that the camera is supposed to be a quiet voyeur, an entity that never plays a role in the narrative, as the moment the audience becomes aware of the camera, the reality of what we’re seeing is instantly rendered redundant. The camera is not supposed to impinge on the subject, which is the premise of David Holzman’s Diary, where it doesn’t only feature prominently as a plot point, but serves as a fascinating and insightful device for commenting on the nature of art, with the protagonist using it as a tool to record life around him. However, as the film progresses, we see the subjects interviewed become increasingly hostile towards the presence of the camera.

This reaches a grotesque peak in the climactic moments when David himself starts to feel the discomfort when he realizes the camera has gone from being a tool to an unflinching voyeur of his private life, peering into his every movement. He becomes increasingly hysterical, repeatedly screaming “what do you want?” at the seemingly inanimate object, as he finally comes to terms with the discerning quality of the lens, which documents every moment, taunting him and exposing his flaws, all of which come from within David and manifest as his complete breakdown, in which the psychology of the film becomes evident. David Holzman’s Diary is an incredibly intelligent film that has a lot to say about both the mind of the artist, and the broader experience of existence, and how we both make and consume art, which is far more complex than simply being the intrinsic need to satiate some desire for entertainment. A quietly revolutionary film, which may have incidentally inspired a countless number of similar works that parody (or pay homage to) the documentary format, which is still one of the most interesting forms of filmmaking. David Holzman’s Diary proves that a fictional pastiche to non-fiction filmmaking can often be more authentic than real ones, which speaks directly to the nature of documentary filmmaking, and how it is often not always as genuine as it would appear. Ultimately, this is a daring work made during an era in which the ambition was to be mainstream, and where this film chose to boldly deviate from expectations and occupy its own niche, which results in a poignant, hilarious and unexpectedly charming comedy that manages to incite some grave conversations, all the while never taking itself all that seriously.