It’s a beautiful summer on Fire Island – Dan (Bruce Davison) and Peter (Richard Thomas) are a pair of young men spending their vacation on the beautiful beaches and luxurious cottages of the idyllic shoreline. They meet Sandy (Barbara Hershey), a young woman, who enters into their lives when she asks them to help her rescue an injured seagull, which she soon adopts. The trio become very good friends, finding a certain kinship in each other and frolic through the lazy days of summer, engaging in a series of misadventures, far from the discerning eye of any adults, with their parents having their own personal distractions that allow their children the free reign to make the season their own. Eventually, they find themselves feeling something deeper – a burgeoning sexuality begins to take over, with the seeds of romance being sown as they slowly start to surrender to their urges, coming into a youthful lust that allows them to explore their carnal curiosities, experimenting with feelings and sensations they had previously never come this close to experiencing. They also soon meet Rhoda (Catherine Burns), a shy milquetoast teenager who is seemingly repulsed by the vulgar actions of her new friends, but is secretly equally as allured to their visceral adventures, gradually entering into the fray as a way of exploring her own individual quandaries, and feeling the sense of belonging she had previously never come close to experiencing in her everyday life. These young people soon find themselves maturing over the course of a few months that any of them are unlikely to ever forget, with the lessons they learn about themselves and each other making an indelible impact on their future lives, and changing how they perceive the world around them.

It’s a beautiful summer on Fire Island – Dan (Bruce Davison) and Peter (Richard Thomas) are a pair of young men spending their vacation on the beautiful beaches and luxurious cottages of the idyllic shoreline. They meet Sandy (Barbara Hershey), a young woman, who enters into their lives when she asks them to help her rescue an injured seagull, which she soon adopts. The trio become very good friends, finding a certain kinship in each other and frolic through the lazy days of summer, engaging in a series of misadventures, far from the discerning eye of any adults, with their parents having their own personal distractions that allow their children the free reign to make the season their own. Eventually, they find themselves feeling something deeper – a burgeoning sexuality begins to take over, with the seeds of romance being sown as they slowly start to surrender to their urges, coming into a youthful lust that allows them to explore their carnal curiosities, experimenting with feelings and sensations they had previously never come this close to experiencing. They also soon meet Rhoda (Catherine Burns), a shy milquetoast teenager who is seemingly repulsed by the vulgar actions of her new friends, but is secretly equally as allured to their visceral adventures, gradually entering into the fray as a way of exploring her own individual quandaries, and feeling the sense of belonging she had previously never come close to experiencing in her everyday life. These young people soon find themselves maturing over the course of a few months that any of them are unlikely to ever forget, with the lessons they learn about themselves and each other making an indelible impact on their future lives, and changing how they perceive the world around them.

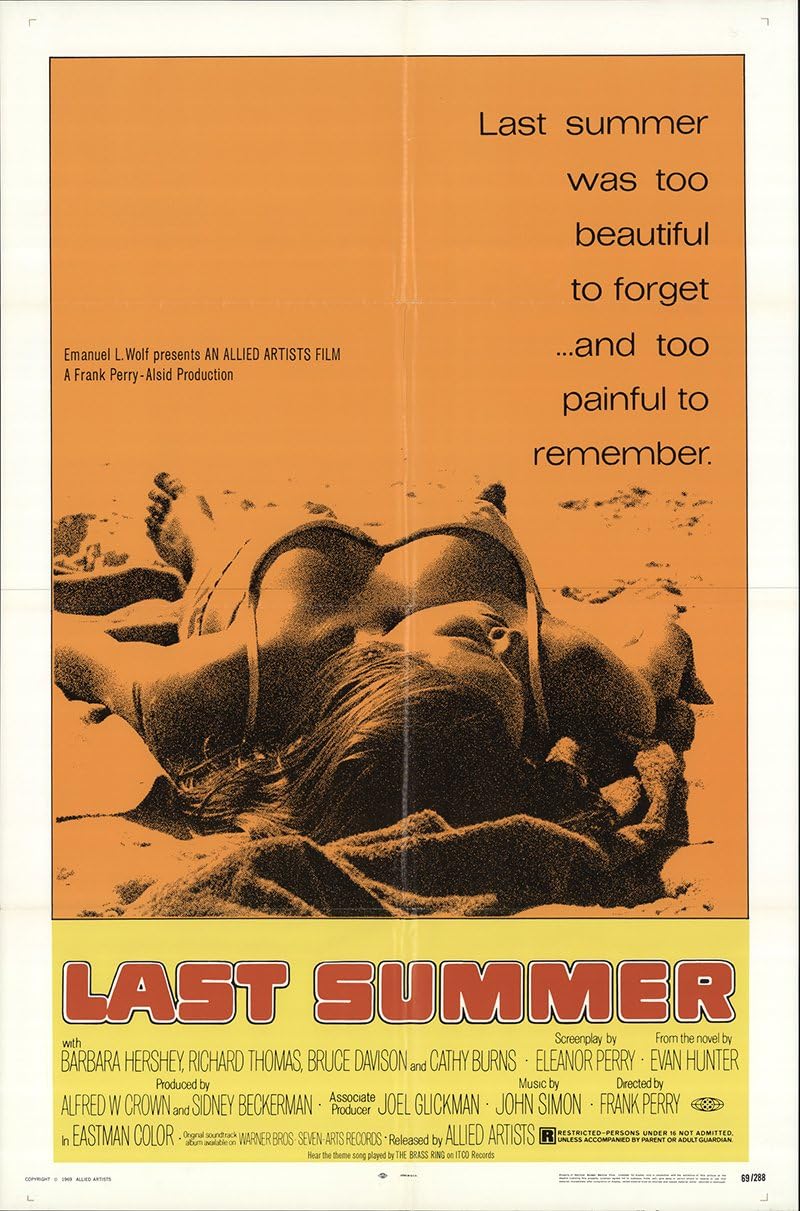

Frank Perry was a true American master whose talents were dismissed as a result of some major disappointments (but later successes, such as in the case of cult classic Mommie Dearest), and ultimately a forgotten auteur whose style and skills have gone far too underpraised, especially considering how a good portion of his work was incredible. Last Summer, based on the novel by Evan Hunter, is one of his crowning achievement – a powerful coming-of-age drama that strips away all cliches associated with the genre, delivering one of the most harrowing accounts of adolescence ever committed to film, challenging many of the qualities that tend to go unexplored in more acceptable works. A haunting tale of reckless youth and the mistakes we tend to make in the ambiguous space between adolescence and adulthood, Last Summer is an extraordinary expression of pure anguish, a complex portrayal of the boundless curiosities, and difficult consequences, of coming of age, particularly in a time when sexual liberation is not only accepted but seemingly encouraged. Perry was certainly not a stranger to provocation, and he takes a difficult story and turns it into something that could have so easily been either a lurid, exploitative film or an uncomfortable morality tale that cautions us to believe that any kind of desire is inherently wrong. Instead, the director puts something together that feels remarkably effortless and easygoing at the outset, but steadily devolves into something far more unsettling as it goes on, while still remaining relatively unadorned, with only brief moments of intentional sensationalism, used as a plot device to portray the sordid curiosities of the protagonists.

It’s not coincidental that Last Summer was made when it was – it feels like a film that works as a multigenerational film, with the general appearance of one of the many entertaining but mindless beach movies of the 1950s, the themes of the sexually-liberated culture of the 1960s, and the growing ambition of the steadily-rising New Hollywood movement, which was still in its infancy, but would make considerable leaps not too long after this. A truly independent film in all senses of the word, Last Summer is an exceptionally unique portrayal of adolescence, delivered without the innocuous sentimentality or toothless execution that tend to be omnipotent in these kinds of films, especially those produced during this period, where teenagers weren’t individuals as much as they were theoretical concepts, homogenous entities that exist to enthral and entertain, but rarely be meaningful, fully-formed figures all on their own. This seems to be the central focus of Last Summer, which may appear to be just another entertaining romp that sees a group of relatable teenagers learning about the world – and while this is true to an extent, the brilliance underlying Perry’s work here is in his careful use of avoiding the cliches, and instead deviating entirely from expectations, taking inspiration less from previous representations of these themes of maturing into adulthood, and more from the school of neo-realism, which is a clear influence on this film, particularly in how Last Summer is frequently quite stark and distressing, leading up to a truly mortifying conclusion that leaves the viewer, much like the characters, in complete shock. Drawn from many sources, not just the original novel, Last Summer is a fresh approach to a tired genre and one that may still be a daring, risky exercise in portraying the true nature of life, regardless of how heartwrenching it may be.

Sexuality is not a subject that fails to be explored in cinema, even when it comes to bigger productions. The idea of desire is not restricted to speciality cinema, and can easily be explored through more prestigious projects. While audiences at the time may not have agreed that Perry was making some artistically significant with Last Summer, it only took half a decade of retrospective provocation for Last Summer to benefit from the inevitable cultural re-evaluation, which the conclusion clearly being that it is a masterpiece of the New Hollywood movement, albeit one that has remained tragically underseen for years due to relative obscurity. The subject matter also doesn’t offer anything in terms of convincing agnostics that there is more to the film than just blatant sexual subject matter – the film, much like the novel, places the insatiable desires of its protagonists at the forefront and isn’t ever compelled to soften the intensity of the storyline. The film is intentionally piquant in how it demonstrates the carefree cravings of these young people, not quite crossing over to immorality, but flirting dangerously close to doing so, with Perry having both the skills and restraint to prevent indecency, supplementing it with an unexpectedly elegant approach to something that could have so easily been atrocious in how it handles the often unnerving plot. It’s not very often that we encounter films that manage to explore sexuality without becoming inappropriate, and while Last Summer does have some questionable moments, they never appear to be unnecessary, nor the product of a filmmaker who sought to exploit, and whose intentions were purely to subvert many of the more troublesome quirks of the genre.

In bringing Last Summer to life, Perry employs a quartet of remarkably talented young actors to occupy the four main roles. Bruce Davison and Richard Thomas take on the two male leads, playing characters that appear to be the archetypal desirable blonde surfer-boys, whose friendship we are introduced to in media res, and who serve as the objects of desire for Barbara Hershey’s Sandy, who is once again forged from the fragments of countless tropes that normally go into creating the ideal young woman. What these three do throughout the film is not necessarily play extremely unique characters, but rather challenge the confines of the archetypes they’re tasked with conveying – these are people undergoing a considerable change in how they perceive the world and interact with others, but they’re still essentially foolish young people who make mistakes, and while the film may sometimes make a point of showing their misadventures in a more lighthearted manner, the repercussions are certainly realistic enough to extend them beyond mere cliche. They’re all very good, but its Catherine Burns who leaves the most significant impression in her heartbreaking turn as Rhoda, the film’s most tragic character, a young woman lost in a world she’s never felt a part of. She may only appear towards the beginning of the second act, but the moment she steps on screen, Burns steals the entire film, and whether through her mild-mannered desperation to fit in, or her heartbreaking monologue which sees her relaying the depths of her profound loneliness, Rhoda is an incredibly compelling character. Burns’ expressivity, subtle control of even the most harrowing emotional content and general ability to make a relatively unlikable character into one of the film’s most memorable aspects, all go towards proving this as truly special work by an actress who may have not been able to find a place in the industry, but still left behind one of the most achingly beautiful performances of the 1960s.

There’s a pivotal moment in Last Summer where one of the characters references the adage “idle hands are the devil’s playthings”, which is not just a throwaway line, but a summation of everything this film is saying. Focusing on the lives of four teenagers in the midst of a sexual revolution, Frank Perry manages to make a bold, intrepid statement about coming of age in an era where liberation from conventions is important in how it intersects with our inevitable process of growing into our identity. The film isn’t always very pleasant – there are moments of genuine warmth and good-natured humour, but the film is otherwise quite bleak, with the underlying despair quietly compounding until the climax, where the three more experienced characters surrender to their animalistic urges and express it in a truly unsettling way, resorting to outright savagery, their lust taking control and perhaps changing the direction of their lives because once you have reached the point where your innocence is lost, there is no possibility of returning. Last Summer is a truly beautiful work that deconstructs the various conventions in a genre overwrought with cliche, and instead delivers challenging, complex filmmaking that is almost intimidating in how powerful the message is. Beautifully-composed, told with extraordinary sincerity, and deeply moving, Perry’s film is a masterful character study that conveys the disquieting beauty of existence with grace and poignancy, resulting in a transcendent portrayal of the human condition, where all inhibitions are abandoned for something far more realistic, and truly affecting.

A fine review of a memorable film.