In Shinjuku City, one of Tokyo’s many neighbourhoods resides a small bookshop run by a genial elderly author (Moichi Tanabe). The bane of his existence, as he soon learns, is a young man named Birdy Hilltop (Tadanori Yokoo), a petty criminal who has chosen this particular establishment as the base for his latest series of thefts. He is frequently caught by one of the store’s employees, the ditzy Umeko Suzuki (Rie Yokoyama), who soon finds herself drawn to the thief, and begins engaging in the same kind of sordid activities, with the couple finding almost erotic satiation in breaking the law in such a way. Their relationship flourishes as a result of their unconventional desires, and as they become more embroiled in this tendency towards sexual gratification through stealing property, they begin to see two sides of contemporary Japanese society at the time – the public side, which derides those that engage in such aimless crime, and the more concealed side, which celebrates these activities as a form of liberating oneself from traditions, breaking rules in such a way that no one, other than those confined to the machinations of capitalism, are directly hurt, with the only damage going towards the economy, which the two lovers clearly could not care less about. However, there’s a sense of foreboding danger that encroaches on their unconventional love affair that sees them satisfying their desires through these actions, as they soon learn that there’s always a slightly bigger, riskier crime for them to test themselves with – but their excitement may not last very long, especially as they become more prominent for their tendency towards these immoral activities.

In Shinjuku City, one of Tokyo’s many neighbourhoods resides a small bookshop run by a genial elderly author (Moichi Tanabe). The bane of his existence, as he soon learns, is a young man named Birdy Hilltop (Tadanori Yokoo), a petty criminal who has chosen this particular establishment as the base for his latest series of thefts. He is frequently caught by one of the store’s employees, the ditzy Umeko Suzuki (Rie Yokoyama), who soon finds herself drawn to the thief, and begins engaging in the same kind of sordid activities, with the couple finding almost erotic satiation in breaking the law in such a way. Their relationship flourishes as a result of their unconventional desires, and as they become more embroiled in this tendency towards sexual gratification through stealing property, they begin to see two sides of contemporary Japanese society at the time – the public side, which derides those that engage in such aimless crime, and the more concealed side, which celebrates these activities as a form of liberating oneself from traditions, breaking rules in such a way that no one, other than those confined to the machinations of capitalism, are directly hurt, with the only damage going towards the economy, which the two lovers clearly could not care less about. However, there’s a sense of foreboding danger that encroaches on their unconventional love affair that sees them satisfying their desires through these actions, as they soon learn that there’s always a slightly bigger, riskier crime for them to test themselves with – but their excitement may not last very long, especially as they become more prominent for their tendency towards these immoral activities.

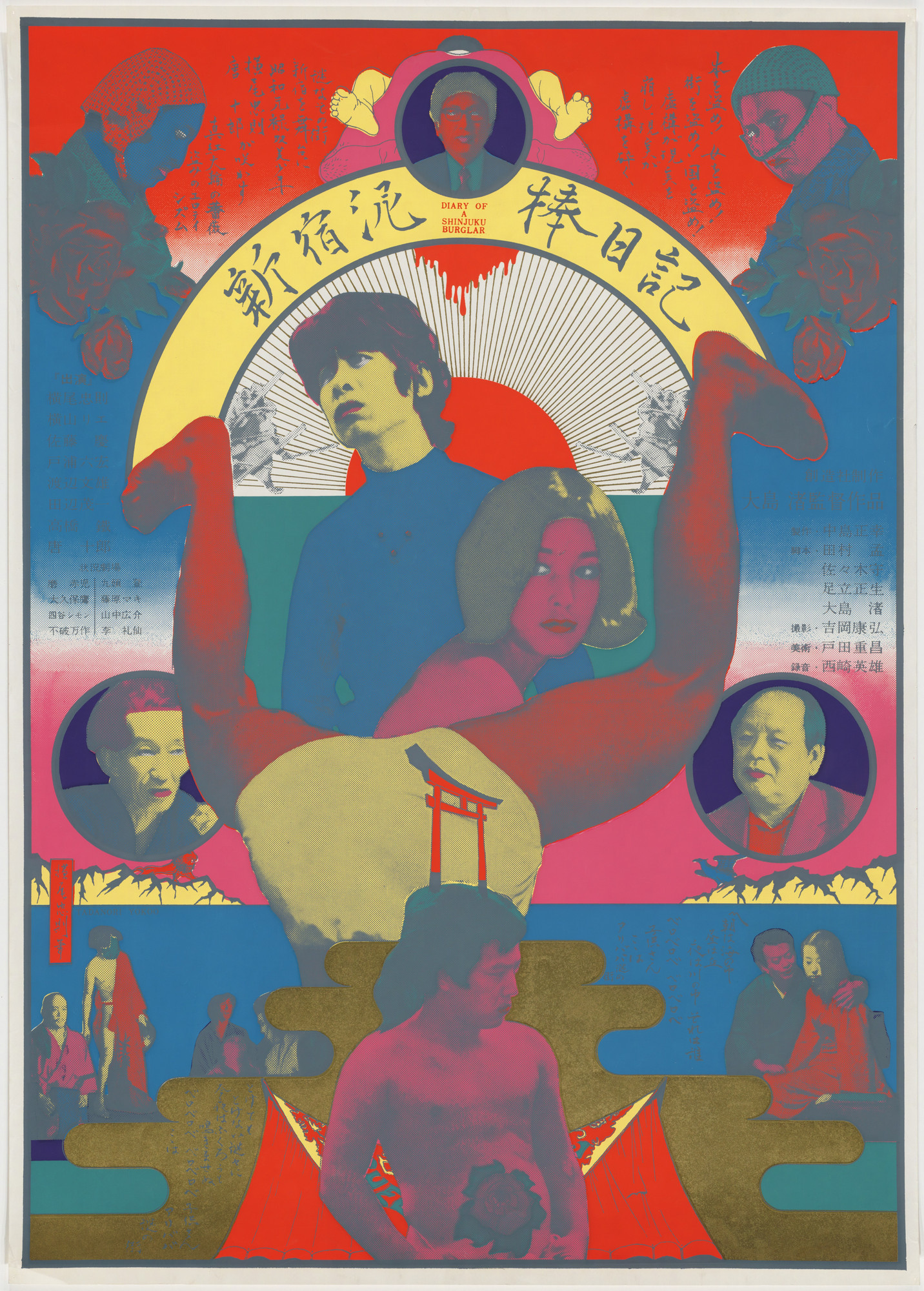

It’s surprising that a coherent plot synopsis was woven together, mainly because if there is one thing we can say about Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (Japanese: 新宿泥棒日記), it’s that lucidity is not a priority. Nagisa Oshima was one of cinema’s great provocateurs, and while this film may not stand out in the same way as some of his other films may (such as In the Realm of Senses and Empire of Passion), it does feature many of the same qualities that made him such an enduringly fascinating filmmaker, and someone whose work, as controversial as it may be, bears extraordinary relevance to the way we view and embrace cinema, especially when it comes to the subject of desire, which plays a pivotal part in the construction of this film. Part of the Japanese New Wave, a period that saw many filmmakers challenging the grandiose heroism, or quiet realism, of their artistic predecessors, and going in search of something more complex. Oshima was certainly a constituent of this school of filmmaking, as evident in many of his work, particularly Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, which sees the director merging fiction and reality in a profoundly interesting way, resulting in a deeply challenging, but effortlessly captivating, work of experimental cinema. It’s appropriate to note that Diary of a Shinjuku Thief is not an easy film – it often defies everything that could be considered sacred in terms of telling a story, opting for a more subversive approach to a set of humanistic ideals that are rarely ever explored through cinema in this way, where we are forced into a position of subservience to a story that only begins to come together in a vaguely coherent way towards the end, and where everything prior to the harrowing, yet oddly hypnotic, climax was merely exposition for a seditious excursion into the human spirit and our various temptations.

Oshima didn’t do experimental work – he made disruptive films, stories that would go against many ideals of filmmaking, yet still remain very much within the social confines more conventional films would. Diary of a Shinjuku Thief is a remarkably simple film – the story of a young woman without any direction falling in love with a petty thief, and not only finding a sense of belonging but also discovering a burgeoning sexuality, is not a story that is necessarily very complex. However, it’s the way in which Oshima delivers this story that makes it special – not only does he manage to remove it from the realm of smut (with this being a remarkably tame affair in terms of how the director uses sexuality as a thematic device, especially in contrast with some of his later work), but he infuses it with a sense of social commentary that makes it an effective satire that provokes thoughts through acidic wit and some extraordinarily well-positioned moments of unhinged surrealism, which work towards creating the atmosphere of unsettling humour, where we see reality reflected in a way that is recognizable but heightened only slightly, to the point where it becomes a disconcerting experience. This directly correlates with how Oshima oscillates between fact and fiction in the making of the film, creating a sense of controlled confusion, designed to challenge the viewer and make us less passive, and more engaged with the story. Oshima seems to be implying that we shouldn’t just peer into this story (as evident by one of the film’s vignettes being focused on voyeurism), but rather be actively working towards deciphering the social meaning behind this very unconventional, but no less brilliant, work of postmodern surrealism.

One of the cornerstones of postmodernism (which is the easiest categorization for this film, despite it occurring just before the peak of the movement), is the amalgamation of reality and fiction, which is something that Oshima does very well in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief. The bookstore that forms the basis for the film is a real establishment operating just as it appears in the film. The owner and employees were not actors, but rather brought into the film to play versions of themselves. Some may think this was due to budget restraints, but considering how Oshima was not a director who thrived on convenience, it had some deeper implication. It gives the film a realism, which is the foundation of the story, and allows the director to venture further into his provocations of the human condition and our occasionally unconventional desires through building on reality, rather than constructing it from inauthentic materials, which is far more common and successful. However, Diary of a Shinjuku Thief is not a film that intends to be pleasing to everyone – its themes of raw sexuality and the glamour of adopting a life of crime are uncomfortable at best, immoral at worst – yet it works in the context of a film that appears to be fully intent on breaking from tradition and going in another direction altogether. In adopting a few brief moments of reality, and repurposing them as fictional through framing them in different ways than they were originally intended to be, Oshima is deconstructing reality and presenting his own, which can sometimes appear to be more authentic than other works that propose to be completely fictional or based entirely on reality.

There’s a truthfulness to this film that is becoming increasingly rare, where the stories we’re presented with are not adherent to the binary of fact or fiction, but occur on a spectrum. This is true of many films produced over the years – the difference is that Diary of a Shinjuku Thief is not against making the fact that every piece of fiction has some element of truth and even the works that propose complete honesty tend to take artistic liberties in some way. Beneath the risqué subject matter, there’s a compelling work of art that challenges the way we engage with stories and the people behind them, particularly in regards to their specific intentions. It works incredibly well, especially if we notice how Diary of a Shinjuku Thief defies categorization, occurring somewhere between psychological thriller and delightfully twisted dark comedy, with enormous overtures of erotic fiction to complement the theme of desire. Oshima takes fragments of other works – Jean Genet’s Diary of Thief, which lent this film its title, recurs throughout the film, as do other pieces of literature and music, making the film quite an elaborate mosaic of influences. This is most evident in the fact that Diary of a Shinjuku Thief does not follow a single narrative thread, but rather leaps between different episodic moments – some are reenactments of memories, others brief sequences that demonstrate the general social milieu around this time, others just explosive moments of unhinged surrealism that don’t make much sense in terms of the story being told, but rather contribute to the general atmosphere of warped reality.

The film rebels against metanarratives, as proven by its complete dismissal of many of the most distinct qualities of lucid storytelling, instead adopting something far more narratively insurgent – arguably, this isn’t a method that should become commonplace (as it needs a director who is comfortable enough with his or her artistic profession, to the point where there is no hesitation to complete disregard the sacrosanct rules of the craft), but when it’s done properly, and with the precision that it needs, it can be extraordinarily effective, as evident by this film, which dares to challenge more than just art, but life itself. Oshima’s work here, while requiring a lot of attention, flows with the sincerity and dedication that we’ve come to expect from a director who is never afraid to unsettle for the sake of telling a compelling story. Composed of moments derived from both reality and fiction (consider the frequent use of on-screen text that gives arbitrary information about different parts of the world, which bear no relevance to the film other than contributing to the general sense of narrative unease), and you’ll come to realize precisely what it is that makes this such an incredibly effective work of postmodern semi-fiction, which is perhaps the most accurate way to describe this film. It’s not an easy film, featuring the same uncomfortable thematic content as some of Oshima’s other work, but which still manages to be quite hypnotic, with the true impact of Diary of a Shinjuku Thief coming when we are most transfixed by its carefully-curated chaos, which harbours deeper social messages, the meaning of which can only be found by viewers who are willing to surrender themselves to this film’s unconventional charms and dive into the gorgeously demented mind of a filmmaker whose provocative nature concealed a keen understanding of social structures, so much that he was able to make a film fashioned from sheer absurdity, but which still manages to be more resonant than most others.