One of the most unexpected, but no less pleasant, surprises of recent years was the realization that not only is Greta Gerwig a tremendous actress, but she’s also got all the qualities of a great director as well. Her first solo directorial effort, Lady Bird, has often been considered one of the best films of the decade, mainly for its empathetic portrayal of a regular teenage girl yearning for liberation from her banal suburban existence, done through an effortless combination of humour and pathos. Many of these same qualities are present in Gerwig’s sophomore feature, in which she adapts Louisa May Alcott’s timeless classic, Little Women, a film that may have some minor shortcomings, which are overcome by a general sense of warmth and enduring joy that makes this one of the year’s most exceptionally beautiful films, a poetic ode to sisterhood, individuality and following your ambitions, wherever they may take you. A powerful exploration of major existentialist issues, particularly in how we develop as individuals, Gerwig pays remarkable tribute to an author whose work, particular this story, have inspired generations of readers around the world – and with this film, Gerwig has now give audiences the opportunity to rediscover the enchanting tale of the March sisters and their extraordinary misadventures, all of which serve to bewitch and inspire, and perhaps even break our hearts on occasion, which is all indicative of a film that intends to do nothing more than just be a poignant, heartfelt tale of humanity and its many idiosyncrasies, something Gerwig has always been very intent on exploring as an artist.

One of the most unexpected, but no less pleasant, surprises of recent years was the realization that not only is Greta Gerwig a tremendous actress, but she’s also got all the qualities of a great director as well. Her first solo directorial effort, Lady Bird, has often been considered one of the best films of the decade, mainly for its empathetic portrayal of a regular teenage girl yearning for liberation from her banal suburban existence, done through an effortless combination of humour and pathos. Many of these same qualities are present in Gerwig’s sophomore feature, in which she adapts Louisa May Alcott’s timeless classic, Little Women, a film that may have some minor shortcomings, which are overcome by a general sense of warmth and enduring joy that makes this one of the year’s most exceptionally beautiful films, a poetic ode to sisterhood, individuality and following your ambitions, wherever they may take you. A powerful exploration of major existentialist issues, particularly in how we develop as individuals, Gerwig pays remarkable tribute to an author whose work, particular this story, have inspired generations of readers around the world – and with this film, Gerwig has now give audiences the opportunity to rediscover the enchanting tale of the March sisters and their extraordinary misadventures, all of which serve to bewitch and inspire, and perhaps even break our hearts on occasion, which is all indicative of a film that intends to do nothing more than just be a poignant, heartfelt tale of humanity and its many idiosyncrasies, something Gerwig has always been very intent on exploring as an artist.

While it may be seen as overly ambitious, Gerwig’s decision to adapt Little Women seemed like a remarkably natural progression, based on her previous work. Even just looking at Lady Bird, we can see similarities between the films – they’re both films about talented young women hoping to break out of their particular social position and explore the world around them, becoming artists that can break through and entertain audiences with their own work, drawn from their own unique experiences, which we are shown in these films. However, not only does Little Women show Gerwig as having refined some of her directorial style, it also affords her the opportunity to leap deeper into the fabric of these tales, telling a coming-of-age story that may appear to have the qualities of many period dramas, but bears very little similarity in how it approaches the idea of growing up, which is essentially what the film is about. One of the more interesting aspects of this film is how personal it feels, despite being adapted from a novel that has been interpreted in so many different ways throughout the years – the director is bringing something of herself into this story, taking the framework Alcott set out centuries ago and building a narrative that not only pays tribute to the original novel but allows it to be used as a way of commenting on themes that tend to still be extremely resonant. Gerwig accomplishes this in many different ways – whether through the script the wrote to interpret the novel in her own way, or the performances she derives from her actors or even the smallest creative detail, she turns Little Women into a wonderful piece of social commentary that breaks through the boundaries of mere literary adaptation and becomes something much more profound.

The excellence underpinning Little Women starts at the very genesis of Gerwig’s decision to adapt the novel, with her approach being one that was not necessarily revolutionary, but rather a more unique way of telling this story. The director set out to craft a film that evokes the spirit of the era in which it takes place (as the Civil War Era certainly had a very distinct atmosphere when represented in fiction, which Gerwig manages to capture very well), but without being overwrought or too focused on the small historical details. Like many of the greatest period dramas in history, this version of Litle Women is less concerned with the precise context, and more the social issues that underly the story and give it such a resonance. She does this by compiling a crew of collaborators that help her realize her vision, allowing this film to extend itself beyond the confines of a lavish costume drama, and into something more special. Alexandre Desplat, undeniably one of the most gifted composers working today, scores the film with such precise, delicate music that often complements the images and brings out even more emotional resonance. Oscillating between melancholy and riveting, Desplat’s score is quite extraordinary and works in tandem with the cinematography by Yorick Le Saux, who does incredible work in capturing the spirit of the era, and shooting the film in such a way that it feels entirely natural, as one of the most significant problems when it comes to period dramas is an overabundance of spectacle, to the point where the narrative is sidelined. This is not the case here, as Le Saux pays attention to complementing the narrative, rather than being a supplement, which ultimately results in a very memorable aesthetic, particularly in how the film moves between time periods, with the only indication of the temporal moment being visually – the childhood days are represented in bold, colourful hues that show the warmth and joy of memory, while the latter period’s colouring is more desaturated and arid, representing the bleak events that befall the family. On a creative level, Little Women is already a marvel – but there are certainly myriad other ways that the film succeeds, particularly in terms of the more traditional aspects of the period drama.

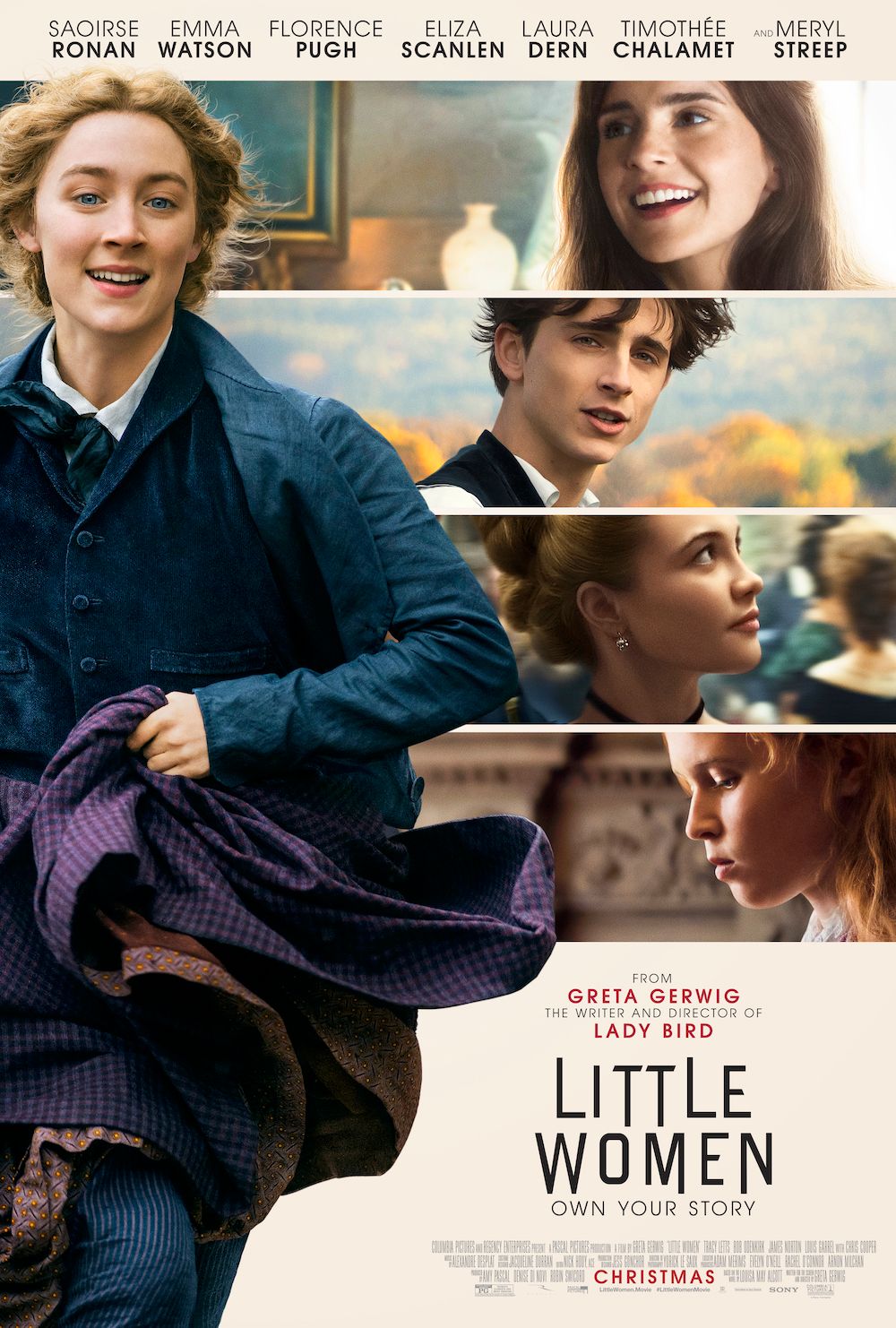

The March sisters are a formidable quartet of literary characters, and there have been many actresses that have taken on one of the roles throughout the years, each one bringing something new to the role. Saoirse Ronan, who has been on an impressive streak ever since her breakthrough in Atonement, takes on the central role of Jo, and proves herself to be someone who can instantly connect with Gerwig’s vision, bringing the same kind of authenticity to this role as she did to the titular character in Lady Bird. Both characters are inherently rebels doing their best to challenge the status quo, which is increasingly difficult, considering their entire existence is based around certain normative standards. Ronan is an incredible actress, and while she is considerably more subdued here than she was in the previous film, she’s extremely effective and finds a certain elegance in a character that thrives on subtlety. Jo may be central to the story, but she isn’t the entire focus, and thus the rest of the sisters are given attention as well. Florence Pugh, an actress undergoing a meteoric rise to fame, is terrific as Amy March, the most volatile of the sisters. The actress gives such a layered performance – she’s the only one who undergoes some form of change throughout the film, as we see her progress from adolescence to adulthood, with Pugh being equally adept at both sides of the role. Eliza Scanlen is quietly brilliant, stealing the film as Beth, who is the most tragic character – reserved, shy and ultimately the source of the film’s most emotional arc, she is the heart of the film. Unfortunately, Emma Watson struggles to meet the same standard – not necessarily terrible, her acting seemed particularly laboured, especially in contrast to the more subtle work done by her co-stars. Meg is a compelling character, having to serve as the shepherd of the family as the oldest sister, but she ultimately becomes entirely forgettable in the part, with the audience struggling to emotionally invest in her. Watson is a charming actress, but she clearly struggled with adapting to the film’s tone, an essential component to the film’s success, and something the rest of the actresses seemed to realize.

However, Little Women doesn’t only thrive on the main characters, but also the memorable supporting roles as well. Laura Dern is at her most empathetic here, playing the matriarch who has to raise four girls on her own while her husband volunteers in the war. Dern brings such a warmth to the role (contrasted with her chilly performance as Nora Fenshaw in Marriage Story), and adds so much soul to a film that works best when it is at its most endearing. Meryl Streep has a small but memorable role as Aunt March, the prickly spinster whose approval the March sisters desperately crave – not necessarily a role with much substance, but essentially just comic relief, Streep has a lot of fun (she’s just as magnetic here as she is when she leads a film) and manages to play excess while still demonstrating considerable restraint. Timothée Chalamet continues to prove himself as a firm constituent of the future of acting with this film, where he gives possibly his best performance since his own breakthrough a few years ago. His charm, wit and subtle approach to the role make his Theodore “Laurie” Laurence truly compelling and distances the role from the allegations that the character exists solely as an object of desire. Little Women is populated by a variety of other small roles that leave an imprint – Jayne Houdyshell is a scene-stealer as the loyal housekeeper who is as responsible for raising the March sisters as their own mother is, and Chris Cooper does a great deal with the role of Laurie’s grandfather, an otherwise forgettable character that is here repurposed as the embodiment of the older generation, both in terms of wealth and wisdom. The cast of Little Women really rises to the occasion, and while there are some very strong elements outside of their performances that allow the film to be as successful as it is, its these characters, and how they’re brought to life by this dedicated ensemble, that leaves a lasting impression.

Ultimately, what makes Little Women such an extraordinary film is the script. Despite possessing some incredible acting skills, and establishing herself as a formidable director, Gerwig was always been strongest as a writer – and her work here is not merely translating the novel to the screen in the same way other literary adaptations do, but rather an in-depth collaboration between the original and her own interpretation, with Gerwig engaging with the text in such a thoughtful way, extracting the important themes and channelling into her screenplay, which ends up being as faithful an adaptation as we could hope for, especially because it isn’t just a direct transplant of Alcott’s novel, but rather an active rendition of her broader thematic content. This ultimately leads us to the quality that makes Little Women such a mesmerizing experience – it is the most compassionate film of the year. It’s a warm, funny and endearing drama about ordinary people, and while it may be set in a period none of us experienced, the story it tells will resonate with each one of us. There is something for everyone in this film – whether it be the touching portrayal of family, the historical context that the film is situated in, or the steadfast approach to exploring your own identity and coming to terms with the concept of individuality. The film will often take the viewer by surprise – there are several moments of genuine emotional eruption that are delivered with such authenticity, with the film taking us to sometimes unexpected places, even though we are fully prepared for what has famously been established as one of the most heartbreaking, yet extraordinarily uplifting, stories in fiction. Gerwig really puts everything into this script and provides us with one of the most earnest, stirring tales of family seen in a very long time.

The warmth and charm brought to this legendary novel by cannot be understated – Greta Gerwig proves that her directorial debut was only the beginning of what should be an exceptional career, where her extraordinary talents can be used to guide even more fascinating stories to the screen. She breathes new life into Louisa May Alcott’s timeless tale of sisterhood, looking at the beauty underlying that film. The soulfulness brought to this film is not only the result of a director fully committed to telling this gorgeous story but also an incredible cast, led by the astounding Saoirse Ronan and Florence Pugh, who continue to prove themselves incredible performers who are going to define the next generation of actors. Supporting performances from Laura Dern, Meryl Streep and the rest of this ensemble give the film even more nuance and allow it to flourish in beautiful ways, facilitating the quietly rebellious exploration of the human condition, and the minutiae that make it such a fascinating subject, and something that falls right within the kinds of stories Gerwig has been involved with for her entire career. Little Women is a film that we can easily analyse too much, but we can’t neglect that beneath the veneer of the period drama that this film does so well, there’s a passion pulsating, with the film being a spirited glance at life and its many eccentricities, told by the most empathetic of filmmakers. It’s gorgeous work, and a truly exceptional piece of cinema that transcends the boundaries of literary adaptation to become one of the year’s most moving films, and a singularly unforgettable experience that will leave you emotionally devastated and optimistic about the chance that anything, even one’s wildest dreams, are entirely possible if you just have a little hope.