When it comes to insatiable tension, no one seems better suited to engage in a rare form of artistic anarchy quite like Josh and Benny Safdie, who continue to establish themselves as firm constituents of the future of filmmaking and directors who are well on their way to defining the current era of cinematic storytelling. Uncut Gems is an outright masterpiece, an anxiety-inducing black comedy that sees the directors, already known for their unconventional penchant for exploring the dark side of humanity, descending into complete social chaos, delivering a deceptively brilliant work of truly extraordinary proportions, a disorderly assault on the sense that leaves the viewer utterly exhilarated. They once again navigate through familiar thematic territory – anyone who has seen some of their previous work will recognize many of the qualities that lead them to this point – and take on another ambitious portrayal of the human condition, exploring the depths of mortal psychology through a captivating journey into the mind of one man slowly losing it as a result of his own poor decisions, and an all-encompassing greed that leads him down a path of debauchery. From the outset, we can proclaim Uncut Gems as being utter chaos distilled into a singularly brilliant vision, a dark tale of addiction and despair told through the lens of acidic humour and extreme violence, with every individual element of this film converging into a delightfully offbeat experience that can either repulse or bewitch (and sometimes manages to even do both) in its endeavour to beguile the audience and ensnare us in its meticulous adventure into pure social mayhem, done with the precision the Safdie Brothers have mastered over the course of their fascinating career, and with the detail we’ve come to expect from directors who infuse such a frantic energy into every one of their incredible films.

When it comes to insatiable tension, no one seems better suited to engage in a rare form of artistic anarchy quite like Josh and Benny Safdie, who continue to establish themselves as firm constituents of the future of filmmaking and directors who are well on their way to defining the current era of cinematic storytelling. Uncut Gems is an outright masterpiece, an anxiety-inducing black comedy that sees the directors, already known for their unconventional penchant for exploring the dark side of humanity, descending into complete social chaos, delivering a deceptively brilliant work of truly extraordinary proportions, a disorderly assault on the sense that leaves the viewer utterly exhilarated. They once again navigate through familiar thematic territory – anyone who has seen some of their previous work will recognize many of the qualities that lead them to this point – and take on another ambitious portrayal of the human condition, exploring the depths of mortal psychology through a captivating journey into the mind of one man slowly losing it as a result of his own poor decisions, and an all-encompassing greed that leads him down a path of debauchery. From the outset, we can proclaim Uncut Gems as being utter chaos distilled into a singularly brilliant vision, a dark tale of addiction and despair told through the lens of acidic humour and extreme violence, with every individual element of this film converging into a delightfully offbeat experience that can either repulse or bewitch (and sometimes manages to even do both) in its endeavour to beguile the audience and ensnare us in its meticulous adventure into pure social mayhem, done with the precision the Safdie Brothers have mastered over the course of their fascinating career, and with the detail we’ve come to expect from directors who infuse such a frantic energy into every one of their incredible films.

Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler) is a very successful businessman working in the jewellery district of New York City. He has amassed a considerable amount of wealth through his various dealings (some of it being ethically dubious, with Howard being in the company of some truly unsavoury individuals), and passes the time making elaborate bets that subsequently get him in trouble with many different loansharks, who grow weary of his arrogant approach to his gambling addiction. However, Howard’s resourcefulness always gets him out of a difficult situation, using his talent for persuading even the most intimidating of adversaries to give him another chance to prove himself. His most recent acquisition (and subsequent loss) is a large stone which he purchases from Ethiopia, which contains a gorgeous uncut gem that he is hoping to sell for an immense amount of money that will hopefully make him even richer – only to find himself engaged in yet another twisted game of cat-and-mouse with a variety of disreputable figures who would relish in seeing Howard Ratner utterly annihilated. Amongst those he has to deal with in this most recent bout of labyrinthine paranoia are his dishonest assistant (Lakeith Stanfield), who seems far too devious to actually be loyal to his employee, and basketball legend Kevin Garnett, who strikes up a friendship with Howard based solely on his interest in owning this gem, which he believes harbours a particular kind of luck he craves, and which intersects with a group of debt collectors who are after Howard after a foolish bet he made backfired, and who are more than willing to end his career in a very violent and extremely permanent way, should they feel compelled to do so. This all intersects with Howard’s domestic life, where he has to balance being a devoted husband and father, especially in the midst of an impending divorce from his wife (Idina Menzel), who is growing weary of her husband’s transgressions, which conflicts with his carnal desires that he asserts upon his employee and mistress (Julia Fox), who is drawn to Howard not merely through his wealth, but his persuasive charms. Somehow, between all this chaos, Howard has to find a way to survive, which becomes increasingly difficult, especially when there are so many people out to make it even worse.

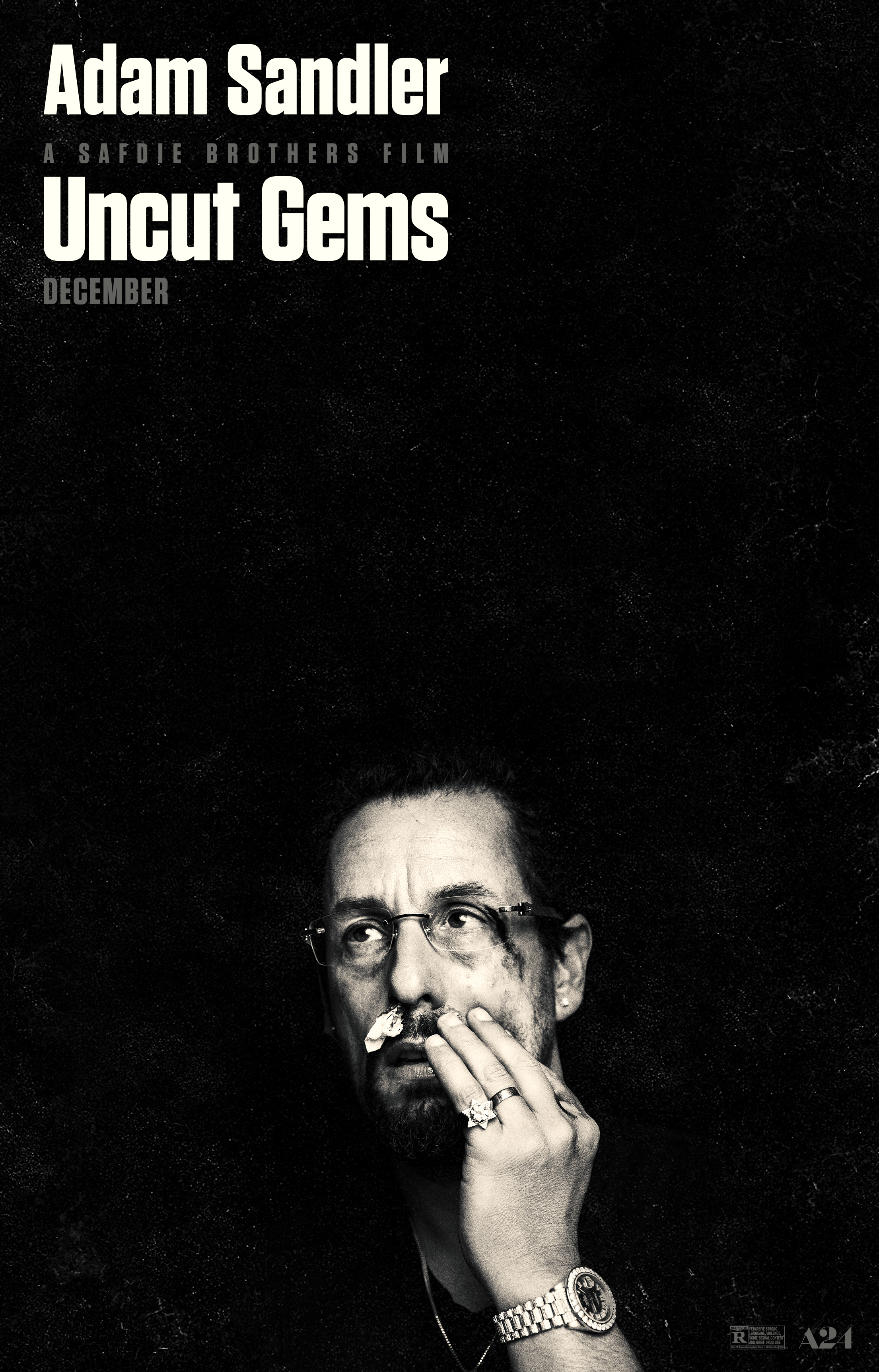

It truly is time for us to put aside his past artistic transgressions and appreciate Adam Sandler for the great talent he is. Uncut Gems is proof that, when offered the opportunity, he can be a remarkable actor, and that most of the weaknesses we previously perceived as being indelible to his work were actually just the result of the material not giving him the chance to prove himself. Obviously we can’t avoid blaming Sandler for engaging in decades of subpar filmmaking, with only occasional moments of genius peppered throughout – he found a niche in the kind of vulgar comedy that have enthralled audiences for nearly three decades and reviled the majority of critics, who found his personality grating and his talents almost non-existent, but which tended to be enormous successes that earned him legions of fans. However, Uncut Gems does afford him some form of contrition, and he takes the opportunity to give what I can call, without even a hint of hesitation, the performance of the year. Prior to this film, Sandler giving even the slightest hint of a good performance was almost newsworthy, as the default opinion was that he’d once again rehash the same childish tropes that the vast majority of his characters demonstrated. This was certainly not the case here, as the genesis and terminus of Uncut Gems rests firmly on the shoulders of a man who absolutely no one, not even his most ardent admirers, ever expected to give a performance of this calibre. This isn’t Sandler doing what he does best with a good script (as was the case with stronger work in films like Punch-Drunk Love and Funny People), but a complete transformation – Sandler has never been this good, particularly because he sheds every quality that made him something of a reviled figure, and builds an entirely new character, unlike anything we’ve seen him do before. It does take some time to acclimate to what Sandler is doing in this film – you’d certainly be forgiven for thinking that he was giving the same loud, crass performance as he normally does, just in the context of a more prestigious film. Yet, as the film progresses, the layers start to fall away, and the vulnerability Sandler brings to this performance becomes clear, with the actor becoming almost unrecognizable in the process, demonstrating himself not merely as being a great screen presence, but a compelling character actor as well.

Howard Ratner is such a riveting individual, and the actor brings such depth to the role, we simply just can’t look away. Sandler commands the screen with a ruthless intensity seldom seen before – it doesn’t matter that there is an ensemble cast of some incredible actors around him, because we just can’t divert attention from the savage vigour Sandler brings to the role. There are not enough words to describe the experience of seeing an actor who has been so underestimated (granted, by his own poor decisions, and his tendency to choose less-than-ideal projects) for so many years, giving a performance that will undoubtedly be seen as a defining moment in contemporary filmmaking – it is already being proclaimed as one of the most impressive performances of the year, so there’s very little doubt that future generations will look back at Sandler’s work here and be amazed that someone who is so often associated with low-brow, poorly-made comedy could find it within himself to surrender to the talents of a pair of intrepid filmmakers, who recognized his innate, but rarely exploited talents, giving him the performance that will stand as a landmark in his career. This isn’t Adam Sandler giving a decent performance by his standards – it’s an astonishing portrayal by a talented actor who defies every preconceived notion of what we thought he could do, and delivered the most unexpectedly poignant performance of the year. Moreover, his work alongside each of his fellow actors here is also testament to his incredible generosity as a performer – Uncut Gems is centred on Howard, but Sandler reigns his performance in enough to allow the likes of Idina Menzel (another absolutely dynamic presence, and someone who deserves much more film work) and newcomer Julia Fox, as well as smaller roles by Kevin Garnett and Lakeith Stanfield, to flourish as well. The Safdie Brothers do wonderfully in bringing this film to life through the characters, never resorting to stereotypes, which is an increasingly impressive fact considering how this film relies so much on preconceived notions of certain subsets of the population. Everyone in this film is incredible, and manage to hold their own against Sandler, even when he is at his most unimpeachable.

The Safdie Brothers not only derive a great performance from Sandler – it is tempting to associate this film with the idea that he’s finally given the performance we’ve all been waiting to see for years, but we can’t deny that Uncut Gems is a remarkable film all on its own merits and that while Sandler is central to the film, and lends it a lot of what makes it successful, there are qualities outside his performance that should be noted. The directors capture New York City in a way that hasn’t been seen in such a way since Sidney Lumet and a young Martin Scorsese and his contemporaries were directing these kinds of films in the 1970s. It’s not uncommon for films to be inspired by these previous works – there are innumerable films that cite Mean Streets, Serpico and Taxi Driver as influences, which is perfectly adequate, but also a tendency that has become worn out by this point. The difference with Uncut Gems is that despite being very heavily inspired by these films, the directors are not resorting to merely paying homage. Instead, they embrace some of the fundamental qualities that made these such captivating works in the first place and manipulate them into their own vision. They aren’t paying tribute to their cinematic predecessors, but respectfully challenging them by taking some of their features and making it their own. This leads to a refreshing sense of narrative cohesion, where the story can go in its own unique direction without ever needing to align itself with what has been done before. This is not the first time The Safdies have made it clear how they are both enamoured with cinema enough to adopt, but creative enough to adapt, which is a quality more filmmakers, especially those that proclaim themselves apostles to New Hollywood, should consider following. They set an example with Uncut Gems, showing how you can be both respectful and defiant to the art that inspired you, taking fragments of the sources that inspired you and creating an entirely new mosaic that bears both similarities to the classics, and establishes an entirely new constituent into the canon of great filmmaking.

There’s a wickedness underlying this film, a loathsome ugliness that becomes almost hypnotic when coupled with the metaphysical themes brought in by the screenplay, and supported by the general tone set by the directors, who seem to be intent on not clarifying where this film should be categorized, perhaps even establishing an entirely new sub-genre of filmmaking. There’s a grit underlying the film that works alongside the storyline to make Uncut Gems perhaps the most tense film of the year – a daring exploration of the human spirit, done through the guise of exposing the rudimentary components of hypermasculinity and the tendency towards satiating the cardinal desires that lead many people, especially those with the resources, to exploit themselves in different ways. The directors, as they did with Good Time, once again use a relatively simple storyline as a way of commenting on broader existential issues, which they provide through inciting extreme anxiety and paranoia in the viewers, bringing along some truly dastardly surprises to make it even more cataclysmic. The directors are not normally the kind to make obtuse social commentary, but they tend to infuse their films with some underlying meaning, and Uncut Gems is certainly not any different. They bring a sense of discomfort and despair into a film that would have otherwise been a flippant comedy filled with archetypes and excessive violence – and the decision to make the audience lose all ease was clearly not something that should be taken lightly, but worked in the context of this film. It all has thematic resonance as well – its doesn’t strike fear in us just for the sake of it, but rather works as a way of demonstrating the more subtle nuances of the film, complementing the complex contemplations of the human condition that the directors extract with such extraordinary ease and incredible lucidity, never losing itself along the way, which is an impressive achievement, especially for a film that celebrates chaos in such an overtly fascinating way.

Moreover, Uncut Gems sees the directors once again approaching their story through the lens of the most idiosyncratic stylistic choices possible, keeping it grounded while still crafting a stark urban landscape that feels oddly uncanny, once again hearkening to the neon-drench cityscape evoked by Scorsese and Paul Schrader half a century ago. The film sees the perfect coupling of style and substance, with so much of the success coming from how The Safdies work in conjunction with cinematographer Darius Khondji and composer Daniel Lopatin (who also collaborated with the brothers on Good Time under the moniker Oneohtrix Point Never) to invoke a certain atmosphere. The use of colour is once again prominent, with a lot of the story unfolding through the subtle use of different shades, which represent different aspects of the protagonist’s mental state – bright colours alert him to the impending danger, while calmer ones comfort him into the misguided belief that he is invincible. Khondji, a truly remarkable cinematography who has photographed some of the greatest films of all time, manages to work alongside The Safdies in capturing every eccentricity of the film, doing so without it being made so obvious, allowing it to come about naturally, which has been a pinnacle of his artistic career, and proves that it often takes the fusion of the audacity of a pair of young directors and the experience of a seasoned veteran to create something entirely unique and completely unforgettable. The music in Uncut Gems plays as pivotal a role in setting the tone as the visuals, and Lopatin composes one of the most memorable scores of recent years. The constant oscillation between frantic and melodic complements the uneasy theme of the film and creates an unsettling mood that forces us into a neurotic trance, provoking the sensation of inescapable dread, while not abandoning the pitch-dark humour that underpins this film and somehow manages to ground it. The various narrative and creative qualities of Uncut Gems intersect in inspiring ways and demonstrate a keen sense of self-awareness that prevents the film from ever drifting too far from its intentions, and lingering in our memory with a certain ferocity that just can’t be ignored.

Despite being quite an intimidating film in terms of the scope it covers, Uncut Gems can easily be condensed into a single theme that governs almost the entirety of the story. The Safdies essentially craft a story about one man situated in an enormous city, teetering dangerously close on losing all control. New York City takes on a role in this irreverent dark comedy about individuality and identity (or rather, the loss thereof) and how it can be called into question when faced with the menacing shadow of a city notorious for breaking more dreams than it satiated. The directors have always been keenly aware of this fact, making it a common feature in every one of their films to date, whether in the lighthearted romps The Pleasures of Being Robbed and Daddy Longlegs, or in the bleak social odysseys of Heaven Knows What and Good Time. This completes a loose thematic trilogy with these two films, with the filmmakers looking at another part of the city and its eccentric inhabitants, exploring the deranged individual that populate it and contribute to the idiosyncrasies of a city that cinema has always been enamoured with. Uncut Gems takes aim at the idea of greed and corruption, but not only the palpable kind, but also the degradation of the soul. Howard is a compelling anti-hero precisely because he is the antithesis of what a protagonist should be – and we watch, with a voyeuristic curiosity, how he descends further into madness, never being able to stop the inevitable destruction of what remains of his moral fibre. It’s a powerful character study that journeys into the psychology of the main character in a way that is both outrageously funny, but also terrifying, as the erosion of decency represented by Howard and his peers is extremely unsettling, especially through the authenticity the directors brought to this film. There’s a moral grounding to this film which the directors approach with an almost sardonic sense of humour, using this story as a way of commenting on something much deeper and incredibly unsettling.

Uncut Gems is an incredible film – Josh and Benny Safdie have truly confirmed themselves as not just being offbeat independent directors known for their attention to smaller stories, but as filmmakers who are going to define the future of the medium. This film is quite simply an extraordinary accomplishment, the work of directors with a clear vision as to what they want to explore, and the daring brilliance to actually execute it with both style and substance. It helps that they have Adam Sandler giving a performance that will undoubtedly become one of the most iconic of the current decade, where he exchanges some of his most notable qualities for something entirely unexpected. No one could’ve predicted that Sandler was capable of such brilliance, and unlike many of his other forays into more serious material, Uncut Gems is not merely a diversion, but an indelible change – while he may return to doing what he does best, there’s no doubt that this is something that will define this stage of his career. Ultimately, everything in Uncut Gems that succeeds was done as the result of the almost miraculous cohesion of pure, unadulterated anarchy, where various components that normally would not work on their own, but somehow collide in such an effective way, there’s no response other than complete awe, which is something that not many films of this calibre can ever attest to achieving. It takes a lot of effort to make something this disorganized, and it all goes towards the beautifully chaotic vision presented in Uncut Gems, a film that keeps the viewer on edge, and even pushes us over it by the end of this hypnotic artistic excursion into the deranged depths of the human condition.