1917 is the kind of film that thinks it matters more than it actually does, and while it isn’t difficult to see why so many people outright adore this film, there’s a certain quality about it that keeps the viewer at a distance, never quite allowing us into this story, which otherwise proposes itself as a meaningful exploration of the ravages of war. It isn’t a bad film by any means, but rather one that is extremely passable, where it only slightly overcomes mediocrity by the sheer effort of certain visual and narrative choices made by Sam Mendes and Roger Deakins, who try to avoid many of the problems that plague this brand of epic war film (not always succeeding, but at least putting in the effort), delivering something that may be momentarily enthralling, and perhaps even quite interesting at times, but is ultimately a cold experience that never quite makes any real impact outside of the technical marvel, which isn’t anything we haven’t seen before, and a more idiosyncratic approach to the idea of war storytelling, which is perhaps the only unimpeachable merit of the film, even though this still comes with some challenges that a more skilled director than Mendes, whose personal familial connection to the subject matter clearly clouded his objectivity as a filmmaker in how he approaches these characters, would have certainly mended and prevented from resorting to disconcerting cliche on occasion. There isn’t much to 1917 other than its basic story – and perhaps that’s something that we should appreciate because it isn’t often that we’re given such a straightforward war narrative that actively moves from different plot points with relative lucidity. However, there is no denying that, while undeniably a fascinating piece of modern technological filmmaking, Mendes really doesn’t do or say anything that hasn’t been done before, and contributes almost nothing to a film that desperately strove to be something special, coming at as a purely middling attempt at a war epic that gives audiences pursuing that exactly what they want, leaving very little for those hoping for even the slightest amount of depth.

1917 is the kind of film that thinks it matters more than it actually does, and while it isn’t difficult to see why so many people outright adore this film, there’s a certain quality about it that keeps the viewer at a distance, never quite allowing us into this story, which otherwise proposes itself as a meaningful exploration of the ravages of war. It isn’t a bad film by any means, but rather one that is extremely passable, where it only slightly overcomes mediocrity by the sheer effort of certain visual and narrative choices made by Sam Mendes and Roger Deakins, who try to avoid many of the problems that plague this brand of epic war film (not always succeeding, but at least putting in the effort), delivering something that may be momentarily enthralling, and perhaps even quite interesting at times, but is ultimately a cold experience that never quite makes any real impact outside of the technical marvel, which isn’t anything we haven’t seen before, and a more idiosyncratic approach to the idea of war storytelling, which is perhaps the only unimpeachable merit of the film, even though this still comes with some challenges that a more skilled director than Mendes, whose personal familial connection to the subject matter clearly clouded his objectivity as a filmmaker in how he approaches these characters, would have certainly mended and prevented from resorting to disconcerting cliche on occasion. There isn’t much to 1917 other than its basic story – and perhaps that’s something that we should appreciate because it isn’t often that we’re given such a straightforward war narrative that actively moves from different plot points with relative lucidity. However, there is no denying that, while undeniably a fascinating piece of modern technological filmmaking, Mendes really doesn’t do or say anything that hasn’t been done before, and contributes almost nothing to a film that desperately strove to be something special, coming at as a purely middling attempt at a war epic that gives audiences pursuing that exactly what they want, leaving very little for those hoping for even the slightest amount of depth.

The film’s plot is mercifully quite simple – Tom Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and William Schofield (George MacKay) are both Lance Corporals during the First World War stationed in Northern France. They are tasked with a mission that is quite literally life-or-death – they’re assigned to travel to a nearby base, where two battalions are stationing, preparing for an attack on the Germans that will hopefully result in victory. What the unexpecting soldiers don’t know, and the reason the two young protagonists are tasked with delivering a message to them is that the army has received intelligence that the Germans are planning a counter-attack that will be nothing short of a massacre. Blake and Schofield have to navigate treacherous terrain and the lurking threat of enemies just out of sight and hopefully survive to deliver the message that could hopefully save the lives of over a thousand of their compatriots, who believe the attack at dawn is going to be business as usual, not knowing the perils that are awaiting them, should the messengers not appear in time. Along the way, they encounter a variety of other people feeling the burden of a seemingly-unwinnable war, some them being allies that aid them in their journey, others adversaries intent on annihilating them. Ultimately, they have to overcome many insurmountable challenges, both physical and mental, as they race against time to accomplish their mission, regardless of the unknown perils standing in their way.

From the outset, it’s important to mention how 1917 is clearly composed of the visions of two individuals – director Sam Mendes, and cinematographer Roger Deakins. Both notable figures in the industry, this film brought their visions together, as both strove to work on a war film that would change how we perceive these stories. The problem is, as admirable as their efforts, they didn’t quite work together in the way we’d hope. It’s always a wonderful prospect to see filmmakers of this calibre collaboration on high-profile projects that could challenge them both creatively, but even more of a disappointment when we discover that beneath the spectacle, there’s really nothing there. My biggest complaint with 1917, and one that must be noted from the outset, is that it’s just a very uncomfortable film, but not in the way that war films are supposed to be. It’s neither moving nor shocking, with the exception of a few small moments scattered throughout the film where it seems like the filmmakers managed to find the tone they were going for. It’s a bleak film in the way that war films have actively tried not to be – some of the greatest entries into the genre tend to find the balance between recreating the horrors of combat while still keeping it fundamentally human. The same really can’t be said for 1917, which has its moments of genuine compassion, but they’re forced into an already overwrought and excessive demonstration of war, where nothing seems to exist in the mind of these filmmakers outside of replicating the arid landscapes of the First World War, and where the final product is far from being the sum total of the many different parts that could’ve made this a much better film.

Here are two facts I consider close to undeniable: Roger Deakins is one of the greatest cinematographers of all time, and he’s one of the cinematographers whose talents are often wasted when it comes to work that isn’t all that challenging. To list the innumerable accomplishments Deakins is a fool’s errand because he has truly defined modern cinematography in his own indelible way, often when working with filmmakers whose visions he is able to complement and sometimes even improve. Sam Mendes is not a filmmaker who I consider to be anything close to a match to Deakins, and 1917 brought out something in the cinematographer that I resent having to mention: outright laziness. This isn’t to say the film was made without a lot of effort – the decision to have it told in one long, continuous shot was certainly enticing, and we can definitely appreciate the mastery that went into the making of this film. However, what no one seemed to realize when approaching this film in this way is that the result will resemble nothing more than a glorified video game, and there’s nothing quite as uncomfortable as sitting passively and watching the camera follows a group of soldiers through war zones, because in the process, the humanity of the story is replaced with the excessive spectacle, and where the tension is lost due to the preoccupation with getting the perfect shot, or the most seamless edit. There’s no denying that the artistry that went into making this film was astounding – for admirers of cinematography, 1917 is a fascinating experiment, and has immensely acclaimed company in terms of the one-shot approach. The difference with this film is that every bit of it was focused on the cinematography, with very little left over to keep us captivated. The result was that it lost its novelty halfway through, with the viewer now having to desperately search for something else to captivate them after we get over the initial awe of Deakins’ cinematography.

This brings us to the fundamental problem in 1917 – when you look beyond the visual spectacle, there’s really nothing there to hold our attention. I’ll outright say that the writing on this film was bordering on atrocious, with Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns seeming to purchase a dictionary of hackneyed military film terms and phrases, and just splaying the contents throughout the entirety of this film, hoping that some of it will be at least somewhat meaningful or at least be able to masquerade as something close to profound. There is a complete lack of an emotional arc anywhere in this film, which is a product of the emphasis on the visual appearance, with very little being done in regard to telling the story in the way it should be told. We can’t deny that some parts of 1917 certainly are very compelling – after all, war films tend to have a sense of excitement that is often manufactured, but difficult to not feel enthralled by. The difference here is that Mendes’ story just doesn’t last long enough afterwards to make any kind of impression, mainly because everything is so overwrought – there are brief touches of profundity throughout, and when the film gets a grip on what it wants to say, it has the capacity to be really moving. The problem is, these moments are so few and far between, it becomes almost entirely surprising when the film has a touch of emotion because everything around it is so focused on appearing to be aesthetically real, the more subtle nuances are almost entirely lost, which is not only a shame but an outright disappointment, considering that there have been so many war films that have found the space to give the story the attention it needs, not only focusing solely on the more bombastic visual qualities.

Of all the choices Mendes made, the casting of this film was one of his most interesting, but perhaps not the most admirable quality. There is a parade of established actors brought out to do what was likely a single day’s work by appearing in this film in very small roles, with the likes of Colin Firth, Benedict Cumberbatch and Mark Strong lending their credibility as great actors to take minor parts in this sprawling epic that really doesn’t know what to do with them outside of the few minutes they appear on screen. The one player in the supporting cast that deserves some attention is Andrew Scott, as he seems to be the only person who understood that he needed to make the most of his limited time, and in playing the role of the endearingly sardonic Lt. Leslie, he commands the screen, which is more than can be said for any of the other actors who appear in these small roles. However, 1917 isn’t really about them – they’re just additions to an already overstuffed film, where the central roles are occupied by two extremely promising young actors that deserved much better than this – George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman are very good in a film that doesn’t quite know what direction to take these characters, introducing them to us at the outset without much of a backstory, which may be a way of paying tribute to the multitudes of nameless soldiers who risked their lives (and sometimes even lost them) defending their country – perhaps it’s a deliberate narrative choice, but a poor one nonetheless, as both actors aren’t given enough to do in the sense of developing them as individuals. Every actor in 1917 is merely an ornament to Deakins’ sweeping vision, and while there are no shortage of films of this ilk that tend to prioritize the landscape as opposed to the individuals that populate it, the intimacy this film was striving for was almost entirely lost as a result of not giving the two gifted actors, tasked with leading the film, much to do other than navigate the territory and ultimately be the surrogate for the audience. This doesn’t mean both actors don’t try excruciatingly hard to stand out in a film designed to push them aside, and every actor in this film deserved much better.

There’s so much stronger work being done by a variety of other creative people around the intricacies of war, and when you break it down to the most fundamental qualities, what can we earnestly say 1917 contributes to the genre, outside of an ambitious but ultimately heavy-handed technical approach? It definitely is worth seeking out solely for the sake of it being a technical marvel that is begging to be looked at – but once that wears off, it becomes so dreadfully vapid, and it never really captivates the audience outside of delivering the same message about how awful warfare really is. A slow film is perfectly acceptable, as long as the pace has some motivation, and the story there is worthy of being told. 1917 just is not that film, because it really becomes a film far too preoccupied with the opulence of technological advancements to ever actually contribute much, and as striking as it is to watch, we just can’t deny that it never hits the heights of some of the exceptional war films its all too often compared to. Mendes deserves some kudos for taking some risks, but they don’t really amount to anything outside of a perfectly serviceable war drama. It falters the most when it tries to grasp something more meaningful, tumbling down a void of narrative emptiness from which it can’t ever really recover. 1917 is the result of sacrificing the human side of a story for the sake of technological innovation, which is truly upsetting considering the potential this film had. This story warranted a better execution, and the film ended up being horribly disappointing, because this film certainly had the capacity to be something very special in terms of commenting on the psychology of war, only to come up short every time in tried to forcefully infuse some emotion into a film that was already intent on being built more on the gimmick and the images it tries so hard to convey as unimpeachable art than the tragic stories of the war that this film was supposedly derived from – it pays respect to the soldiers, but seems to avoid wanting to tell their story in the way they deserved, which is just another flaw in an already immensely troubling film.

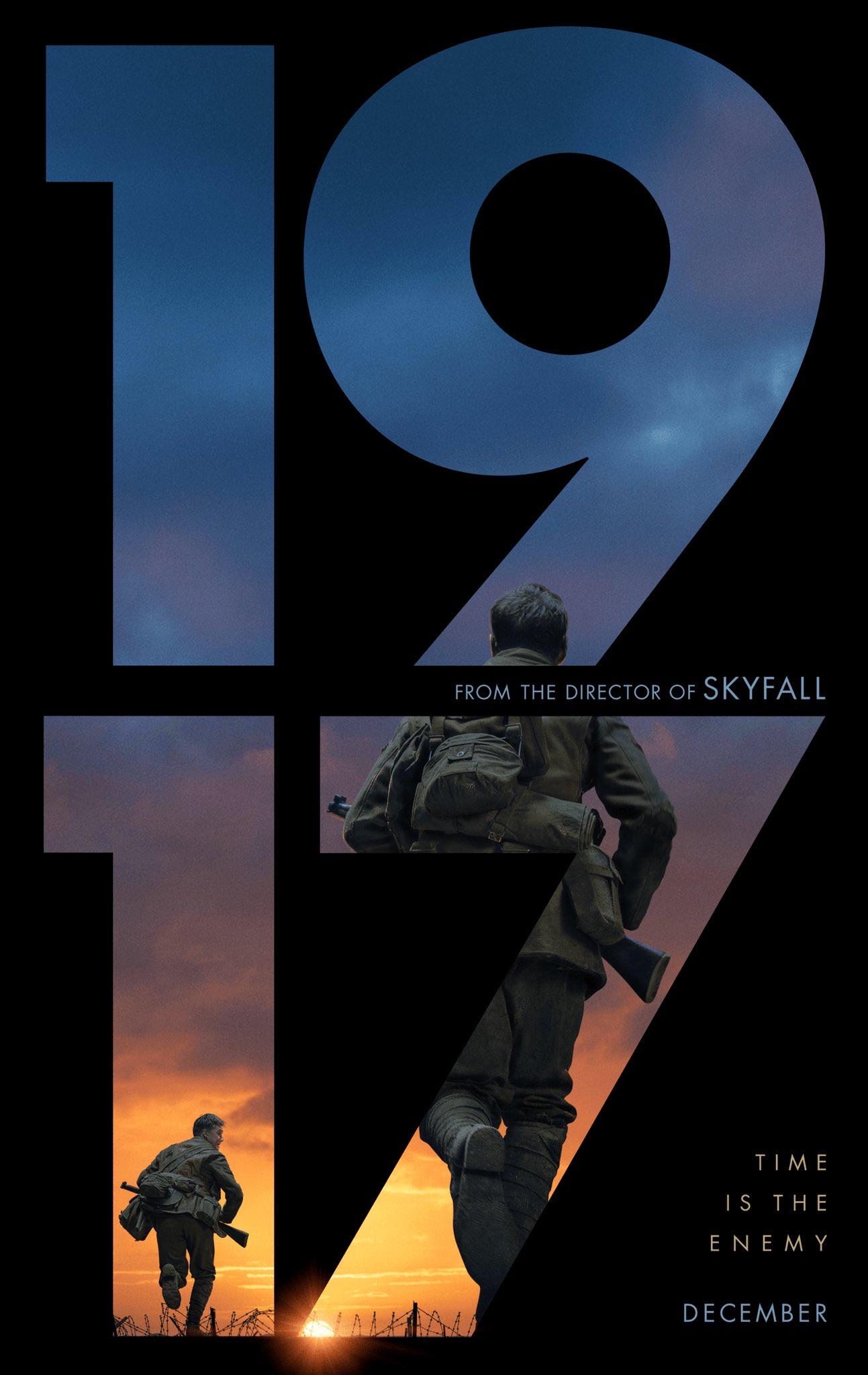

1917 is the ninth feature film of Sam Mendes since winning the Academy Award for directing his debut American Beauty in 1999. With the mild exception of a strong James Bond outing, Skyfall, Mendes has released forgettable cinema. His resume indicates that Mendes is far more drawn to the theater. He served as artistic director for a decade of the highly regarded Donmar Theater in London. He is responsible for the landmark production of Cabaret that focused the show more clearly on the Nazi presence to the point of ending the evening with the emcee locked in a concentration camp marked with the pink triangle, the symbol for homosexuals. His stage work includes major productions featuring noted film stars Nicole Kidman, Julianne Moore, Ralph Fiennes, Judi Dench, and Emily Watson. Mendes is first and foremost a theater director.

Immersive theater is a calculated experience to remove the fourth wall. In a traditional theatrical experience, the proscenium arch separates the actors from the audience. In immersive theater, innovation is employed to remove that artifice of separation and place the viewer into the action. Obviously, this is the intent of Mendes in his latest film 1917. His long single takes serve to encourage us to forget the popcorn, the child kicking the back of our seat, and the annoyance of our feet adhering to a sticky floor. The huge visuals, the surround sound, the documentary-like cinematography all contribute to the goal of placing us in the action.

Mendes is successful sometimes. The surprising death of a boyish soldier at the hands of an injured enemy soldier is a heartbreaking moment that rivets our involvement in the film. The plight of a young woman caring for an orphan infant is equally heart rendering. However, scenes of soldiers trudging through deep muck on the edges of craters beneath grey skies reek of inadequate production design. A moment at the end of the film where a soldier simply walks through a company of 1,600 men, many who are injured from a battle only moments ago, yelling a the name of another character borders on parody. Had the sought after individual been named Wilson . . .

1917 is an above average contribution to the vault of war pictures. However, many, many such films are superior.