Despite the past few decades seeing many filmmakers appropriating some elements of it, the film noir genre has all but faded away, at least in its most distilled form. The neo-noir has replaced it and given audiences some of the most enthralling films in the genre, but the traditional noir has entirely disappeared, becoming a fond memory rather than something that filmmakers actively pursue. This brings us to Edward Norton, who clearly demonstrated an interest in changing this with Motherless Brooklyn, his long-gestating passion project that saw him bringing the complex novel by Jonathan Lethem to the screen, in what can only be described as his attempt to revisit the noir genre in a way that felt like a genuine return to the same ideas, both thematically and visually, that made the genre one of the most endearing. Motherless Brooklyn is definitely not without its flaws – it is overlong, and feels far too convoluted to be a significant entry into contemporary crime cinema. Yet, it does work for a number of reasons – Norton proves himself to be a capable director, in his most audacious project behind the camera to date, and not only does he adapt the novel in a way that felt true to the spirit of Lethem’s vision, he also crafted an authentic 1950s crime drama that has the atmosphere and detail that defined the genre, and the tone to make it an enjoyable, if not somewhat slight, addition to a movement focused on taking a form of art back to its peak.

Despite the past few decades seeing many filmmakers appropriating some elements of it, the film noir genre has all but faded away, at least in its most distilled form. The neo-noir has replaced it and given audiences some of the most enthralling films in the genre, but the traditional noir has entirely disappeared, becoming a fond memory rather than something that filmmakers actively pursue. This brings us to Edward Norton, who clearly demonstrated an interest in changing this with Motherless Brooklyn, his long-gestating passion project that saw him bringing the complex novel by Jonathan Lethem to the screen, in what can only be described as his attempt to revisit the noir genre in a way that felt like a genuine return to the same ideas, both thematically and visually, that made the genre one of the most endearing. Motherless Brooklyn is definitely not without its flaws – it is overlong, and feels far too convoluted to be a significant entry into contemporary crime cinema. Yet, it does work for a number of reasons – Norton proves himself to be a capable director, in his most audacious project behind the camera to date, and not only does he adapt the novel in a way that felt true to the spirit of Lethem’s vision, he also crafted an authentic 1950s crime drama that has the atmosphere and detail that defined the genre, and the tone to make it an enjoyable, if not somewhat slight, addition to a movement focused on taking a form of art back to its peak.

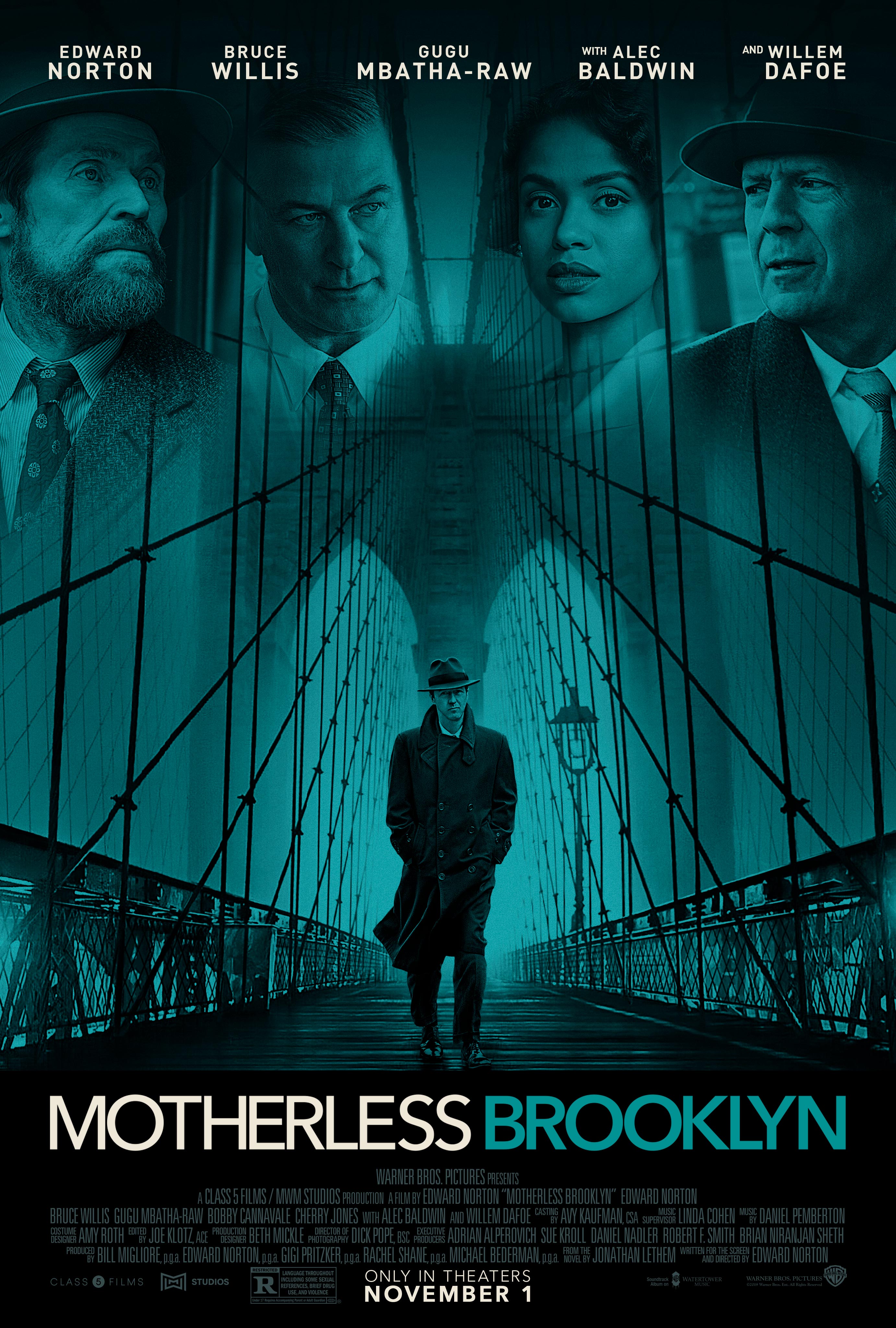

Lionel Essrog (Norton) is a talented private investigator in the 1950s, operating out of a Brooklyn agency run by his friend and mentor, Frank Minna (Bruce Willis). Unfortunately, an investigation the latter is involved in goes wrong, and he dies in the arms of his protege, who is intent on finding the person responsible for such a heinous act. Lionel, who suffers from Tourette’s Syndrome, struggles to fit into society – while utterly brilliant and very dedicated to his job, he’s also socially-awkward and struggles to connect with others, which makes his investigation difficult, especially because it becomes increasingly clear that there was something far more sinister that Frank was involved in. Lionel finds himself venturing deep into the heart of a vicious conspiracy theory that leads him to Moses Randolph (Alec Baldwin), a politician who is allegedly buying buildings in predominantly black areas and demolishing them, in an effort to “clean up the slums”, which is clearly rooted in his own bigotry. Lionel encounters various individuals involved in this plot, whether directly or indirectly, such an eccentric engineer (Willem Dafoe), an intelligent young woman trying to make a name for herself in a society that is inherently against her based on her race (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), and a plethora of other individuals who either aid or impinge our protagonist in his search for answers, with Lionel always being either on the precipice of solving the mystery, or of falling victim to these malicious figures himself.

Edward Norton has been trying to make Motherless Brooklyn for a while – and in his role as lead actor, director, producer and screenwriter, this is clearly a project he is passionate about, with the allegations that point towards vanity ignoring that beneath the many parts he played in bringing this film to the screen, there is a gifted individual intent on telling a story he felt some connection to. Lethem’s novel is an unconventional crime story, as it is both a traditional noir, set in the 1950s and revolving around very familiar themes, but imbued with a certain social relevance that was mostly missing from film noir in past decades, mainly because many of these themes, such as racism and the Civil Rights Movement, weren’t viewed in quite the same way back then as they are now. This gave Norton a lot of freedom in adapting a novel that feels very relevant, even when the period it takes place in would normally date it as being nothing more than a journey back to a bygone era. Motherless Brooklyn feels like the kind of story that was always on the outskirts of mainstream filmmaking when film noir was popular, but could rarely be made unless done independently, which was almost impossible in a filmmaking period where studios reigned supreme. The film may be extraordinary in how it captures the period, taking the raw traditions of the noir genre and infusing it with a sense of modern artistry in how the story is delivered, but it’s the themes that stand out the most, and had Norton not understood that Lethem was far less concerned with the affliction of the main character, and more focused on the underlying social resonance, then this film just would not have worked.

Everything about Motherless Brooklyn obviously revolves around Edward Norton, who is in command of nearly every aspect of the film. Yet, the area in which we should praise him the most is in his acting. Norton is obviously an acclaimed actor, albeit one that has gradually receded from the popularity he gained in the late 1990s. The last decade has seen him take mainly interesting supporting roles in independent films, which hasn’t necessarily changed how we perceive him, but hasn’t afforded him the opportunities he was given when proving himself to be one of the great alternative actors of his generation, with his roles in Fight Club and American History X being truly extraordinary. Motherless Brooklyn saw him returning to playing a central role, albeit under his own direction (some would argue the only director who can work in harmony with Edward Norton is Edward Norton), and he proves that the decision to cast himself in the main role was not borne from vanity – in the part, Norton is able to play upon the character’s idiosyncrasies in a way that was distinctive without ever being forced. The function of the character’s Tourette’s Syndrome is never really explored other than being the root of his social struggles – and while the performance is initially jarring and difficult to connect with, we do manage to acclimate, with Norton never quite reducing the character to just a bundle of tics – it goes without saying that some part of this film is going to be remembered for Norton’s sometimes strange choices with the character, but they’re clearly borne out of affection rather than an attempt to play a character struggling with a mental affliction. He’s excellent in the film, and while it may not be as good as some of his previous leading roles, he does show that he’s still remarkably adept when it comes to playing main characters and that he doesn’t need to be restricted to supporting performances. There’s still a lot for Norton to do in the industry, so if anything, Motherless Brooklyn should be a reminder of just how good Norton can be.

Moreover, Motherless Brooklyn can’t stand entirely on the strength of Norton’s performance – the story employs a wide range of peripheral characters, which means Norton has to share the screen with a panoply of performers, many of which give equally brilliant performances. It is difficult to choose a standout, as the ensemble is so well-composed, each with moments of extraordinary individuality, none of them stand above the other, but rather use their own strengths to be valuable constituents of a cast of truly impressive performers. Willem Dafoe is at his most paranoid as a conspiracy theorist who incites a one-man war against the government, and while there is very little Dafoe needs to prove, especially since his recent career revival where he’s started to take on the role of the elder statesman of character actors, he’s always a welcome presence, not only due to being such an effortlessly charming actor, but because he always puts in effort, regardless of the role. Alec Baldwin has never been angrier (in a film at least), and while it’s often better to reserve judgment on his style as an actor, Baldwin proves himself to still be capable of giving a great performance, just as long as it gives him something to work with. Too much of Baldwin’s recent career choices on television and in film have relied on him riffing off the same set of characters he is normally associated with, so to see him get something perhaps not entirely out of his wheelhouse, but at least interested enough in Baldwin as a performer to give him something to do, was quite heartening and shows that there is still a gifted actor somewhere in there. The heart of the film is arguably Gugu Mbatha-Raw, playing the role of Laura with such intelligence and elegance, she comes across as the only level-headed, logical person in the entire film. Motherless Brooklyn, for better or worse, is constructed out of a set of excessive characters, so Mbatha-Raw’s natural, almost luminous, performance stands out as one that is highly memorable, even if she unfortunately falls to the wayside a bit too often. The entire cast of Motherless Brooklyn is great, and even with smaller performances by Bruce Willis (also giving a very impressive performance that allows him to return to the more complex roles he occupied in the past), Cherry Jones and Michael Kenneth Williams, the film functions as a terrific ensemble piece.

The approach this film takes is quite noteworthy, namely in how it is built as a traditional gumshoe story, but with a twist. This is not the bare-boned film noir made very fast and with low costs, as was the convention in previous decades, but an intricate, plot-driven character study that blends the pulpy charms of crime films with the elegance of modern cinema, where attention can be given to elements like the music, which becomes a character almost entirely on its own here (composed by Thom Yorke, whose recent work in scoring film has resulted in some truly magnificent pieces, especially in this film, where his hauntingly beautiful music complements the film brilliantly), the production design, which brought Brooklyn in the 1950s to life with such precise and meticulous detail, and the cinematography (coming on behalf of the brilliant Dick Pope, whose vision never fails to astound, whether in epic or intimate moments), all of which converge into an enthralling experience. Naturally, this doesn’t mean Motherless Brooklyn is perfect by any means – in fact, it sometimes seems to sacrifice some of the most pivotal elements needed for a film like this to succeed in an effort to capture the bygone spirit – the mood is certainly there, but it tends to come at the expense of narrative cohesion. The film runs too long, and it sometimes before convoluted to the point where it even distracts from the beauty of the film, as it is sometimes difficult to make sense of what this film is trying to say. It leaves too many loose ends to be entirely cohesive, and the ultimate message of this film seems to be lost in the spectacle, which doesn’t squander its chances to succeed, but significantly lessens the impact the final product had.

Motherless Brooklyn is a terrific film – it manages to be an elegant character study that transports us back to the 1950s, both in the atmosphere it evokes, and the visual aesthetic it employs. Edward Norton is exceptional in the leading role, giving one of his most compelling performances to date. He also confirms himself as a gifted director, showing him to have a particular vision his previous forays into filmmaking haven’t quite demonstrated as clearly as this. The film does falter in some aspects, and certainly could’ve been more cautious in how it took a story that normally works better on the printed page, due to the detail a book can provide, but Norton ultimately does succeed in bringing the novel to life in a way that seems relatively accurate and worthy of the various intricacies Lethem novel relied upon in the first place. The film has its various imperfections, which are the product of a film that was made by someone whose authorial voice is still under construction, but also a daring attempt to give audiences the kind of fascinating film noir that is rarely made. The only difference between this film, and something Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum would have done, is that this film has a firm grasp on the cultural pulse, and in combining traditional thrills with potent social commentary, we get a film that may not be as good as it set out to be, but is still intricate, fascinating and ultimately extremely compelling.