There aren’t many people who contemporary audiences can implicitly trust to deliver a film about a haunted dress without descending into parody more than revolutionary auteur Peter Strickland. He is a director who has proven himself to be one of the most peculiar directors working today through a set of films that are both incredibly complex and unquestionably bizarre. In Fabric is one of the most gloriously strange exercises in modern horror, and an exceptional piece of cinema that is singularly unique and so deeply unrestrained in how it approaches a story that is so heavily rooted in absurdity, but never self-serving or sardonic, always being exceptionally elegant, even at its most outrageous. This film is executed with the deft precision the filmmaker has established throughout the course of his fascinating career, which has taken audiences to the most unexpected corners of the human condition, presenting us with stories that absolutely no one could fathom even existed had it not been for Strickland’s brilliantly deranged sense of humour and understanding that it’s very often the most far-fetched ideas that make the most compelling works of art. In Fabric is undeniably one of the year’s most brilliant experiments, a film that voyages to entirely new narrative and thematic territory in its endeavour to not only be extremely original, but revolutionary on its own terms, making it truly unforgettable, for better or worse, and one of the year’s finest achievements on both a creative and narrative level.

There aren’t many people who contemporary audiences can implicitly trust to deliver a film about a haunted dress without descending into parody more than revolutionary auteur Peter Strickland. He is a director who has proven himself to be one of the most peculiar directors working today through a set of films that are both incredibly complex and unquestionably bizarre. In Fabric is one of the most gloriously strange exercises in modern horror, and an exceptional piece of cinema that is singularly unique and so deeply unrestrained in how it approaches a story that is so heavily rooted in absurdity, but never self-serving or sardonic, always being exceptionally elegant, even at its most outrageous. This film is executed with the deft precision the filmmaker has established throughout the course of his fascinating career, which has taken audiences to the most unexpected corners of the human condition, presenting us with stories that absolutely no one could fathom even existed had it not been for Strickland’s brilliantly deranged sense of humour and understanding that it’s very often the most far-fetched ideas that make the most compelling works of art. In Fabric is undeniably one of the year’s most brilliant experiments, a film that voyages to entirely new narrative and thematic territory in its endeavour to not only be extremely original, but revolutionary on its own terms, making it truly unforgettable, for better or worse, and one of the year’s finest achievements on both a creative and narrative level.

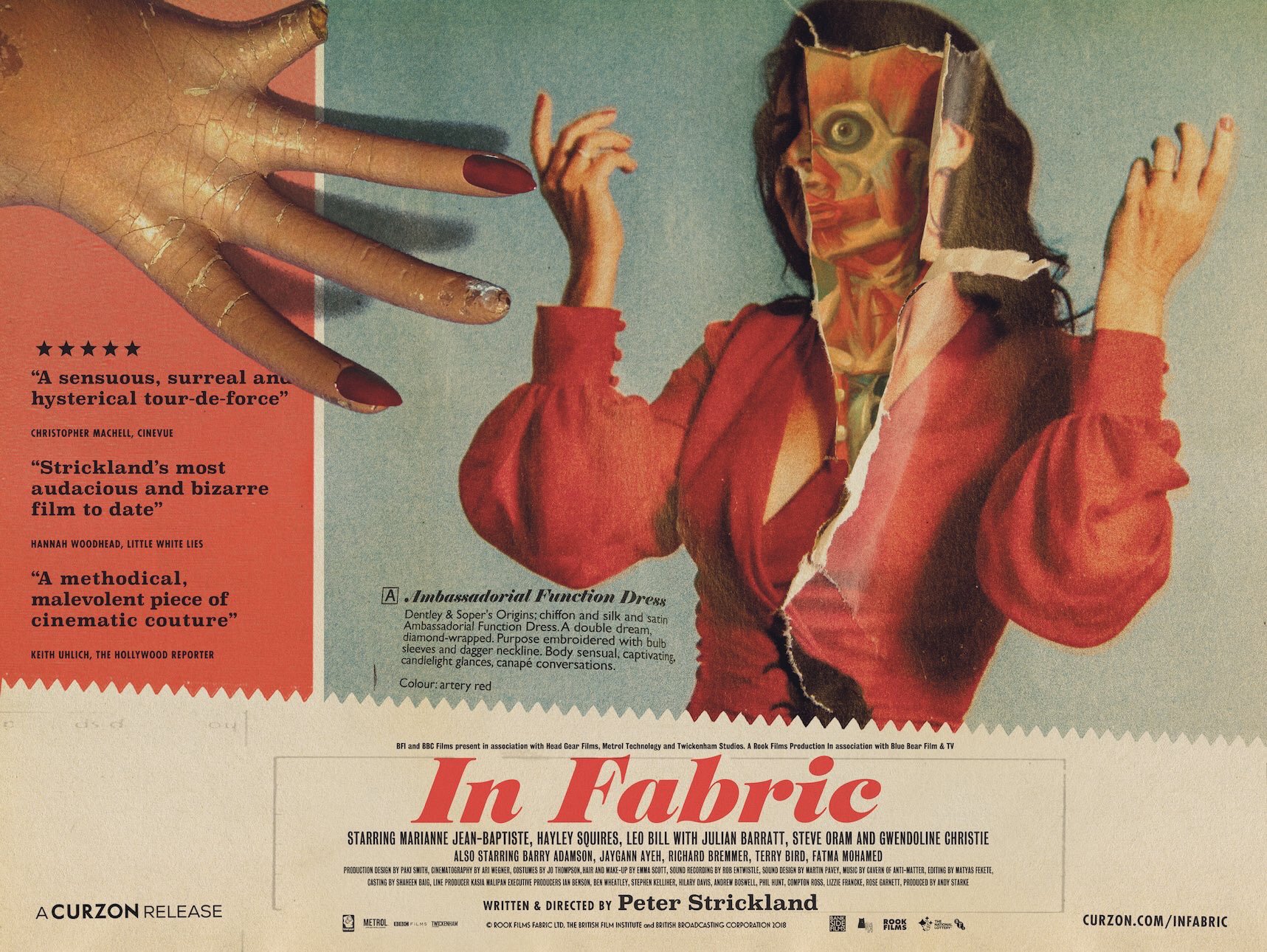

Occupying the surprisingly niche sub-genre of the couture horror, In Fabric presents us with one of the most unconventional horror villains of recent memory – a dress. Prominently displayed in a high-end department store, the blood-red dress draws the attention of Sheila (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), a shy middle-aged woman who is looking to revive her romantic life and find some meaning in the wake of an unfortunate divorce. The dress is not quite her style, but through the coercion of both the strange clerk (Fatma Mohamed), and the almost magnetic pull of the dress itself, Sheila purchases it in the hopes that it will bring her some confidence. It initially does, until it becomes very clear that there is a certain quality embedded in the dress that makes it far more than just an ordinary item of clothing. Sinister events start occurring around Sheila, who finds it initially difficult to comprehend that some fabric could be capable of inciting such cataclysm, but she soon learns that nothing is quite what it seems, and she may just meet a grisly end if she doesn’t part with the dress – but the dress doesn’t necessarily want to part with her quite as quickly. Whoever finds themselves coming into contact with this dress is unknowingly launched into a chaotic version of reality, where nothing seems to make much sense, but the fear that comes with knowing that something is amiss is omnipotent, with the most unconventional of adversaries lurking dangerously close to us, ready to wreak havoc.

What makes In Fabric so brilliant is that despite having one of the most ludicrous concepts ever committed to film (perhaps the most absurd plot since Quentin Dupieux’s masterful Rubber, a similarly strange film about an inanimate object causing trouble), Strickland never approaches the film as if it was anything other than a very serious horror. There’s a deep undercurrent of dark comedy pulsating throughout the film, but which is only made more effective by the fact that everything is played with complete sincerity. There is not a single inauthentic moment to be found anywhere in the film, with the humour coming from its almost rigid irrationality, where we aren’t quite sure if what we are seeing is hilarious or unsettling – it very often tends towards being both in equal measure, and the more we try and penetrate this film and make sense of what it is trying to convey, the less we actually understand. It takes a very serious approach to an increasingly silly idea, which is something that many filmmakers have attempted throughout the years, but have rarely managed to capture with the frantic energy that Strickland demonstrates here. There’s a tonal quality about this film that seems unlike anything we’ve experienced before, and how it combines some thematic concepts that are seemingly incompatible, but done with such magnificent ease here, is only further proof why this isn’t only a profoundly unique film, but also a masterwork of contemporary cinematic artistry, where our perception of reality is not only momentarily shifted, but intrinsically challenged in order to make way for this film’s unconventional approach to existence, which is both fascinating and bewildering, which gives In Fabric its idiosyncratic charm.

This is all very clear from the first moments, when we come to understand almost instantly that In Fabric is not merely a very effective subversion of horror filmmaking – it’s a provocation, not only of the audience, who are dared to laugh at some truly ridiculous filmmaking, but also as a thrilling assault on the senses, where the film finds itself occupying the most visceral segments of our minds, burrowing deep into regions not normally stimulated by art, which serves to create the very uneasy sensations that the film thrives on arousing. Strickland’s influences in this film are simultaneously quite evident, but somehow also very vague, as his style is so distinctly his own, being drawn from cinematic predecessors in a way that suggests an active engagement with their work, rather than simply paying homage. There’s a Hitchcockian sense of suspense that pervades the film through the director’s use of colour, shape and sound, all of which converge to create an inescapable atmosphere of the most palpable and insatiable dread that the viewer is ever going to experience. The saturated colours, jarring cacophony of sounds and unsettling symmetry all work together to create images that should, by virtue of their detail, be extraordinarily beautiful, but are repurposed as deeply horrifying and the subject of the most chilling nightmares that will undoubtedly be incited by the experimental work of the director, whose style comes together to form one of the most singularly abstract pieces of filmmaker.

In Fabric is not postmodernism, despite how it is often compared to some of the great works within the movement – this film exists outside of the realms of any clear categorization and thrives on a certain ambiguity that prevents any form of classification. Yet, it does have one feature that it shares with other works that take similar approaches to familiar concepts – a sense of extraordinary playfulness, albeit one that doesn’t necessarily aim at providing joy. We shouldn’t neglect that this film is not only a very effective experiment in horror filmmaking, but also an outrageous comedy, and Strickland never neglects to infuse the film with a sense of humour that works very differently from how comedy is normally used in horror films. Rather than being a way of finding catharsis in brief interludes of levity, the film uses its darkly comical core as a way of further emphasizing the terror that flows steadily throughout it. Absurdism (rather than surrealism, which I’d argue can’t really be used to describe the film, as it is very much rooted within a recognizable world) has unfortunately been overtaken by the belief that irreverence and defiance of reality make for effective art – it isn’t untrue, but it also neglects the fact that absurdism can also prove to be truly terrifying. Just consider the work of one of the great absurdists of his time, Franz Kafka, who utilized a darkly comical sense of humour not to entertain his readers, but to plunge them even deeper into existential despair – this is where In Fabric resides when it comes to its use of comedy. There’s an unsettling quality in these kinds of stories that hasn’t been explored often – it’s enough to present us with stories of how bleak our existence is – but to still be able to derive humour from them, but the kind that resists pleasure and resembles some otherworldly entity laughing at us, demonstrates an understanding that humour isn’t always a method of finding joy, but can also be a tool for truly unsettling existential horror.

Somehow, despite possessing all the qualities that would naturally make this film an unpleasant ordeal, In Fabric is remarkably enjoyable. It isn’t always clear why this film succeeds in the way it does – it certainly is very well-made, and it has some extraordinary performances (Marianne Jean-Baptiste proves herself to still be one of the most brilliant, but tragically underused, actresses of her generation, and Hayley Squires turns in another memorable performance that solidifies her as someone on the ascent). Yet, there’s something about it that should not have worked as well as it did – Strickland’s approach to the film, which very much indicative of his talents as both a storyteller and visual artist, seems to have been informed by a sense of hostility, perhaps not to the audience, but to the kind of genre he’s working from here. This kind of originality is not found very often, mainly because very few filmmakers demonstrate such lucid disdain for conventions. In Fabric is an experience like no other, and while we do tend to try and rationalize absolutely everything, the only way to truly understand this film is to avoid making any sense of it. It’s an experience that is best approached when we just surrender ourselves to the delightfully deranged vision of a filmmaker who is intent on subverting every expectation he possibly can. Demented, twisted and unquestionably bleak, In Fabric is one of the year’s most audacious pieces of cinema, a grisly horror film that finds the humour in some of the most unexpected situations. Peter Strickland is an absolute genius, and it would appear that with this film, he finally confirmed himself as one of contemporary cinema’s most essential voices, and someone whose work is dark but profoundly fascinating, as demonstrated in this film, which takes the audience to the most unexpected places with elegance, humour and relentless terror. This is a work of chaotic, nightmarish brilliance, and stands as one of the most extraordinary achievements of the year, and a singularly unforgettable masterpiece of modern horror.