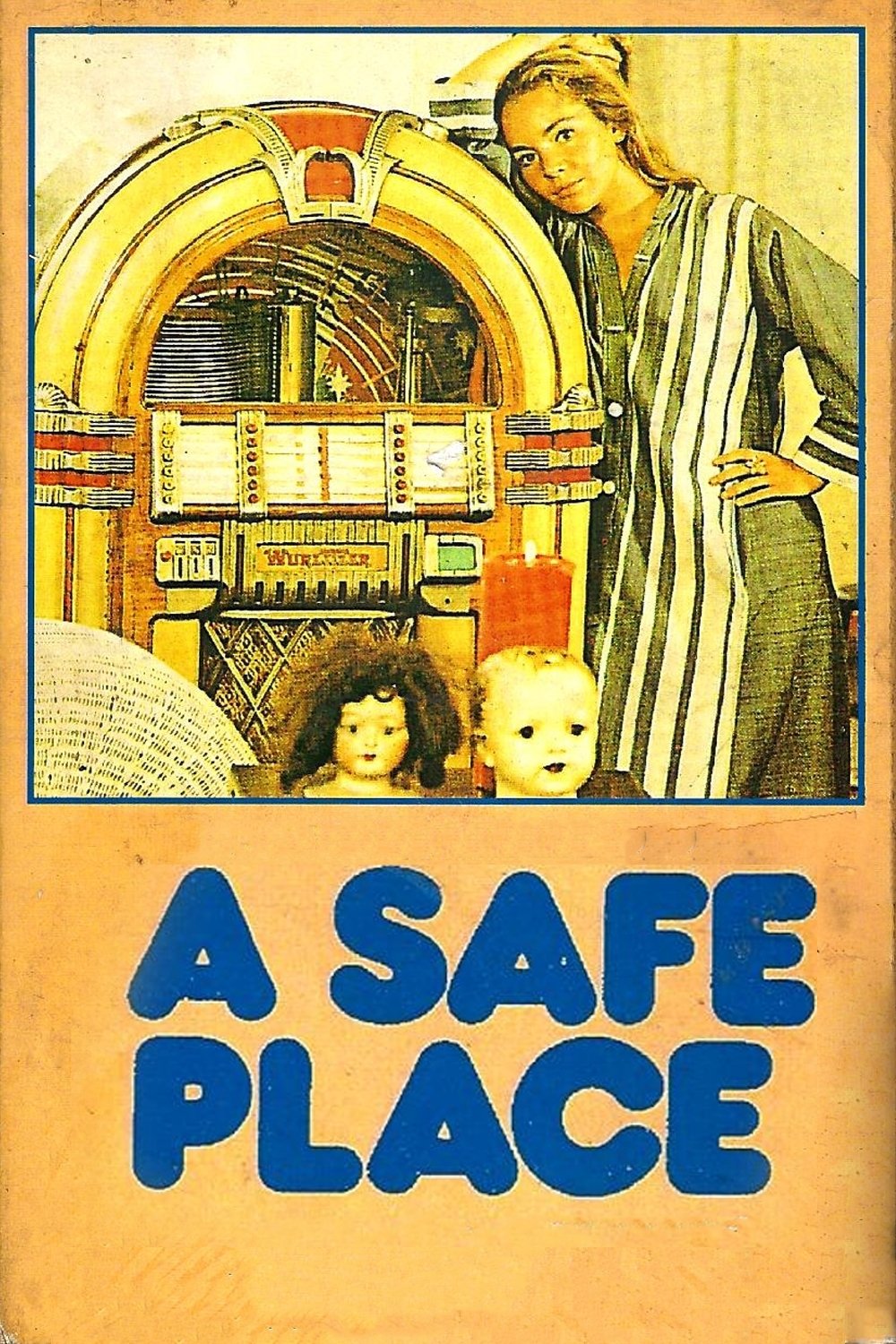

Come for the promise of a stylish New Hollywood fairytale, stay for a heavily-accented Orson Welles taunting an orangutan in-between magic tricks. This seems to be the premise behind Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place, a film that is quite remarkable in precisely how misguided it actually finds itself being, despite all the promise it had on the surface (or at least based on what it appeared to be going for). In no uncertain terms, this film represents artistic incompetence on an almost unprecedented level – how the director managed to wrangle together a film quite as poorly-constructed and convoluted as this warrants some special honour, because its difficult to find something quite as incoherent as whatever clutter he was trying to convince us was some meaningful ode to the human condition. There’s very little else to say other than this film is a tangled hodgepodge of missed opportunities, non-sequiturs (which have never worked in the cinematic format, regardless of how many would argue that some of the great works of arthouse cinema have utilized them, when in actuality even the most scattershot of films tend to have some method behind the madness) and ultimately just dreadful indifference to a medium that has rarely been as unbearable as it is here, making this unequivocally one of the most infuriating films of its period, and the perfect exemplification for why an idea and a camera don’t always make a good pairing when the talent or effort is completely absent.

Come for the promise of a stylish New Hollywood fairytale, stay for a heavily-accented Orson Welles taunting an orangutan in-between magic tricks. This seems to be the premise behind Henry Jaglom’s A Safe Place, a film that is quite remarkable in precisely how misguided it actually finds itself being, despite all the promise it had on the surface (or at least based on what it appeared to be going for). In no uncertain terms, this film represents artistic incompetence on an almost unprecedented level – how the director managed to wrangle together a film quite as poorly-constructed and convoluted as this warrants some special honour, because its difficult to find something quite as incoherent as whatever clutter he was trying to convince us was some meaningful ode to the human condition. There’s very little else to say other than this film is a tangled hodgepodge of missed opportunities, non-sequiturs (which have never worked in the cinematic format, regardless of how many would argue that some of the great works of arthouse cinema have utilized them, when in actuality even the most scattershot of films tend to have some method behind the madness) and ultimately just dreadful indifference to a medium that has rarely been as unbearable as it is here, making this unequivocally one of the most infuriating films of its period, and the perfect exemplification for why an idea and a camera don’t always make a good pairing when the talent or effort is completely absent.

It’s not that A Safe Place doesn’t do well by its story (the main cause behind the majority of cinematic failures in this specific genre) – it’s that it quite certainly doesn’t have a story to begin with. Based on what can be derived from the brief interludes of lucidity that come all too infrequently, the film follows a woman – whether her name is Susan or Noah is never made clear – who resides in Manhattan, and lives in a permanently dreamlike state, fluttering between reality and fantasy as she ponders the upper-class minutiae she so proudly demonstrates. Whether entertaining one of her two boyfriends (played by Philip Proctor and through no fault of his own, Jack Nicholson), or being advised by an enigmatic magician (played by someone resembling Orson Welles, but lacking the nuance, charm or outright likeability that made him such a film icon) who seems to live in Central Park, where he has a certain difficult relationship with a group of caged animals. This is essentially the extent of what A Safe Place implies is the story – it apparently blends the past and the present in how it views a young woman’s decay into debauchery as a result of her materialistic life built on a veneer of superficiality and subjectivity. It’s also just a film about an ordinary woman without even the slightest defining trait, other than her penchant to act in a way different from how any human being who has ever breathed would behave, which apparently makes her such a resonant and endearing character. Yet, for the course of this film’s (mercifully short) running time, we are supposed to care about her and her exploits, and consider her the perfect embodiment of the modern American woman. How this film got away with such dreadful characterization is truly beyond me, and will be something I’ll ponder far longer than I’ll ever remember this disastrous attempt at character-driven drama.

Jaglom’s directing doesn’t do any favours for this film either – not only is he unable to find time to actually construct a story, he focuses far too much on the spectacle of being experimental, but without any of the ambition or even talent that went into avant-garde cinema – the only explanation for A Safe Place that could save it from total damnation is if we view it as a parody of the overly-dour experimental films produced over the course of the previous decade – it doesn’t make up for the outright failures that pervade the film, but it allows us to actually not dismiss this as the mess it is. Unfortunately, Jaglom even manages to betray our benefit of the doubt by so clearly demonstrating his sincere conviction that what he was making was actually something audiences would want to watch, and not retreat with rapidity normally reserved for real natural disasters. The production notes of the film always tend to mention how it was assembled from fifty hours of footage that Jaglom and his actors filmed during the course of the production. Fifty hours without so much as even an iota of a storyline seems far too exorbitant, but considering what a calamity the film ended up being, it’s absolutely plausible. The most accurate description of this creation is that its the embodiment of amateur incompetence masquerading as meaningful, dreamlike surrealism, falling short of any coherent idea that would make it even a little bit convincing.

It’s almost as if Jaglom assembled the rejected sequences and unnecessary off-cuts of the great works of surrealism, and repurposed them around this film, without actually adding to them in any way, rather intentionally putting them together in a mosaic of images that fail to converge into something resembling a plot, or a clear message, or even something that resembled a film. One of the most frustrating pieces of cinema I’ve seen in a very long time, A Safe Place borders dangerously close on becoming dreadfully pretentious – actually, it even achieves it in many instances, taking full advantage of its independent sheen to distract from the fact that it is the epitome of poor filmmaking that came about as the result of either overestimating one’s talent and standing in the industry, the arrogance to believe that any scrappy upstart can make a film if he or she possesses the ambition or a combination of them. The only reason that it doesn’t completely envelope the film is that even the most cynical of viewers will genuinely hold onto the belief that the film will actually improve – why else would something with this pedigree squander all of it? What we realize all too late is that this film is a bold exercise in disregarding the viewer as a valuable entity, and rather using them as a tool for the director to explore his own artistic cravings. Jaglom truly believes that audiences will believe that his incoherent ramblings are some profoundly meaningful art, without realizing that very few viewers are as incompetent as him when it comes to recognizing what constitutes a story, and what is just a meaningless set of images passed off as art.

There’s just nothing to enjoy about this film, and there’s even the possibility that everyone involved in this film knew exactly how excruciating an experience this is, and intentionally made something that would annoy the viewer. The film does have some notable performers in its cast, such as the likes of Orson Welles and Jack Nicholson, who give enigmatic performances – mainly because it’s a complete mystery why they agreed to appear so prominently in a film that not only vehemently refuses to make any sense, but also makes insulting use of these gifted actors. The extent of Welles’ co-lead performance as a character of indeterminate nationality of species entails sitting on a variety of park benches and boulders in the middle of lakes, as well as the occasional interaction with cage animals that are clearly just as surprised to see Welles as we are. This is at least something compared to what Nicholson had to work with, with the majority of his time on screen being spent walking in circles and flashing that distinctive grin that implies that he knows that he was coerced into starring in this mess, so the audience will be forced into watching it. On the bright side, the film does make great use of Charles Trenet’s iconic song, insofar as its clearly the only song they could wrangle the rights to, so you can be sure it’s showing up at every opportunity where ethereal French pop standards can only benefit the baffling images we’re presented with.

For Henry Jaglom, making a film is not as difficult as it appears – his genuine belief in making A Safe Place is that through the combination of poorly-conceived ideas, a modest but relatively decent budget and the conviction that just throwing together some arbitrary scenes interspersed with commentary of some form suddenly qualifies something as a film, which is the most insulting and frustrating part of the film as a whole – it doesn’t even bother to acknowledge that it’s a mess, but clearly does recognize it, never actually striving to be any better than it was. Disjointed, uncomfortable and just utterly aimless, A Safe Place fails to deliver even a moment of pleasure – it manages to be the most unfunny comedy of its era, the most meaningless philosophical exploration of the human condition, and quite possibly the worst example of experimental film. This is the kind of work that incites disdain for avant-garde art – it doesn’t show incredulity towards the concept of metanarratives so much as it fails to even find the time to open a dictionary to look up the definition for any of those words. Jaglom throws every idea he had into this film and hopes that something would stick – the problem is, absolutely none of it did. A daunting, bothersome experience, there are few films as ludicrously unnecessary as this one, and to call it a total dud would just be an insult to the dud industry. If there is any meaning to this film, it certainly evades me, and perhaps the best aspect of A Safe Place is that it eventually ends, even if it feels like an eternity until we are graced with the liberation of knowing that we’ll never have to endure this bewildering mess ever again. In the end, the safest place turned out to be very far from this travesty of a film.