If there is one way to describe The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (German: Die Angst des Tormanns beim Elfmeter), it would be as a film the perpetually occurs at intersections – whether being constructed at the crossroads of genre, narrative conventions or nation, this is a film that borrows heavily from a variety of sources, but never in a way that seems gaudy or inappropriate. The second film directed by the masterful Wim Wenders, who is clearly demonstrating his exceptional control over his visual and narrative style in this very strange subversion of film noir conventions, The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is a daring social odyssey that keeps everything extremely simple, and demonstrates that sometimes the most effective films are the ones that say the least at the outset, but slowly come to develop deeper meanings through the interplay between story and style, something the director has been remarkably adept at throughout his career. This is a complex film that is clearly inspired by the work of many previous filmmakers, but takes on qualities of its own that are equally as impressive, and proves that even in the formative years of his career, Wenders was a director whose grasp on his craft was undeniably his own, possessing the ability to make something so meaningful, yet so unfurnished in excess. While it is the director at his most raw and experimental, where he is still trying to find his footing as a filmmaker, there’s very little doubt that he made something extraordinary with this intimate character study that unsettles just as much as it enthrals.

If there is one way to describe The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick (German: Die Angst des Tormanns beim Elfmeter), it would be as a film the perpetually occurs at intersections – whether being constructed at the crossroads of genre, narrative conventions or nation, this is a film that borrows heavily from a variety of sources, but never in a way that seems gaudy or inappropriate. The second film directed by the masterful Wim Wenders, who is clearly demonstrating his exceptional control over his visual and narrative style in this very strange subversion of film noir conventions, The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is a daring social odyssey that keeps everything extremely simple, and demonstrates that sometimes the most effective films are the ones that say the least at the outset, but slowly come to develop deeper meanings through the interplay between story and style, something the director has been remarkably adept at throughout his career. This is a complex film that is clearly inspired by the work of many previous filmmakers, but takes on qualities of its own that are equally as impressive, and proves that even in the formative years of his career, Wenders was a director whose grasp on his craft was undeniably his own, possessing the ability to make something so meaningful, yet so unfurnished in excess. While it is the director at his most raw and experimental, where he is still trying to find his footing as a filmmaker, there’s very little doubt that he made something extraordinary with this intimate character study that unsettles just as much as it enthrals.

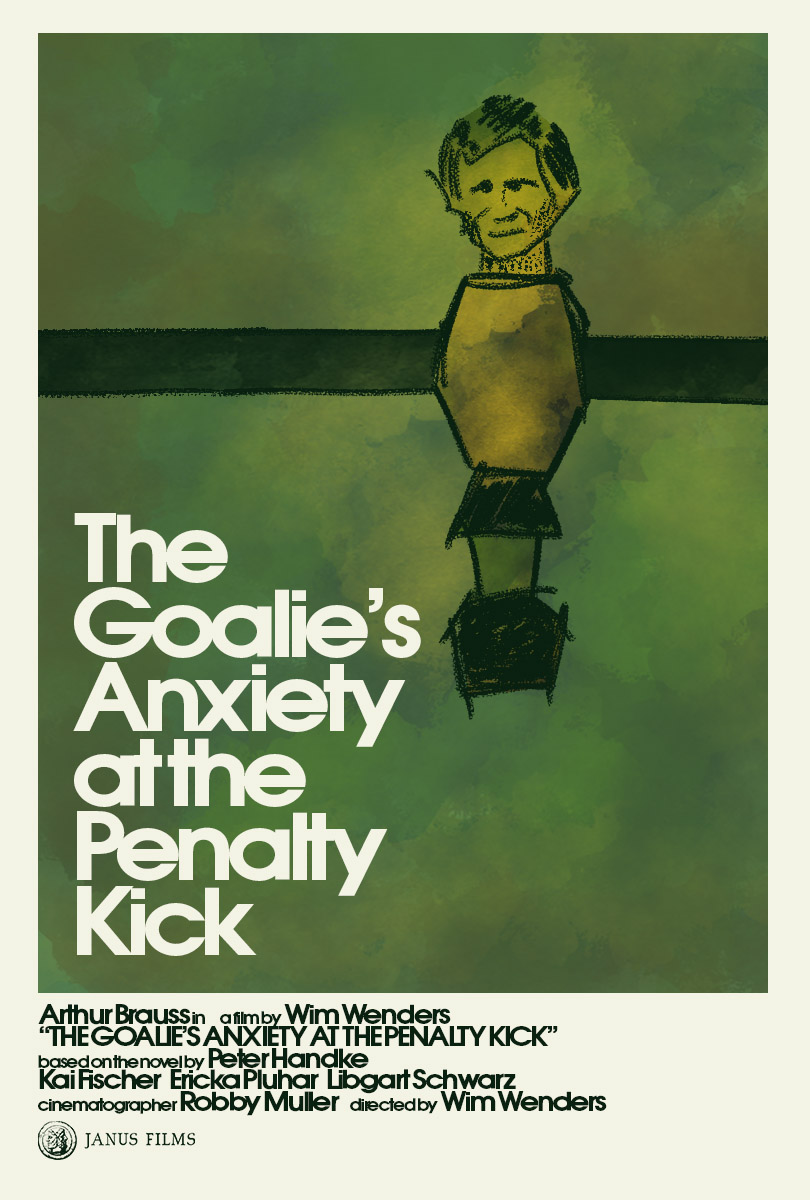

Bloch (Arthur Brauss) is a short-tempered goalkeeper for a small German soccer team. At the outset of the film, Bloch finds himself sent off the field for poor behaviour resulting from a surprise goal that snuck past him, leading to his team losing the match. He finds himself aimless after the game has ended, his career in professional sports seemingly being called into question. One evening, he encounters Gloria (Erika Pluhar), the genial cashier at the local cinema that our anti-hero frequents. He very soon develops an infatuation on the woman, which eventually leads to a very brief romance between the two, which is cut short by Bloch murdering her for ambigious reasons, possibly as a result of his own mental fragility caused by feelings of inadequacy and instability. Now somewhat on the run, he takes refuge in a small town, where he constantly visits a bar run by an old acquaintance of sorts, and where his crimes become the subject of a tabloid sensation, where the mysterious murderer is a captivating subject for many of the inhabitants, who don’t realize the person they’re so terrified by resides alongside them. Ruminating over his choices, not only the accidental murder, Bloch discovers that he may not be nearly as important as he used to believe himself to be – a former soccer star who has begun to recede into obscurity, there doesn’t seem any way to escape, other than to take the easy route of rash decisions, such as ending the life of an innocent person, and coming close to doing it again several times.

The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is undeniably the work of Wenders, containing many of the quirks and qualities that can easily be used to identify the work of a filmmaker who may have taken on many different genres, but still utilizes the same finite set of concepts in whatever project he’s working on. Ideas such as overt masculinity, the loss of innocence and mysterious identities take the foreground, as do concepts such as transportation (Wenders seems to have a genuine interest in movement, as all of his films see characters in motion from one point to another, both physically and mentally), existential angst and the intersections between German and American life, reflected in the director’s tendency to always celebrate American traditions through the lens of the German culture that has proudly adopted them, especially at this temporal moment, where the nation had only been facing the turmoil incited by the erection of the Berlin Wall for little over a decade – communism on one side, freedom on the other. There is a sense of social anxiety that extends beyond the confines of the protagonist and his own troubles with coming to terms with a slowly changing system of traditions (even if the actual political issues are not directly evident in the film, rather being concealed within moments of apparent inconsequentiality), but to the nation as a whole. There’s a general atmosphere of despair governing these characters, which allows The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick to grow into a poignant piece not only about one man’s journey to self-realization, but also a profoundly moving commentary on German society at a time when these kinds of films, ones that provide some sense of cohesion to a fragmented nation, were entirely necessary.

The film also employs the director’s ability to blend genres together, creating a film that is equal parts psychological drama and film noir, but one where the conventions are all subverted in favour of a more unique approach to well-taut genres that were already established, inspiring the director to transport their qualities out of their country of origin, and into his own. The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is a film that doesn’t tend to follow one particular story, rather being a series of moments in the day after the titular character commits a heinous crime, itself a response to his frustration with having cost his team the game a few days before. It follows many of the conventions of the film noir, specifically in the part of the leading character being a mysterious loner who seems to be far more world-weary than he initially appears, and who finds himself embroiled in a complex plot. However, in the case of this film, the story is shifted from the large, smoke-filled urban centres that they normally take place in, and moved to the German countryside, where these events transpire in small taverns and quaint apartments, or in the open fields of Europe, which give the main character the chance to contemplate his actions, as well as the way forward (no one seems to be able to centre a film almost entirely around contemplative issues quite like Wenders), in a setting so detached from what we normally see for this kind of film, it lends The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick an even more complex tone, where its sedate execution contrasts with the very bleak subject matter.

Looking at The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is an interesting endeavour because we can read it as an early forerunner of literature that critically explores a character who embodies all the qualities of toxic masculinity, a concept that has only properly entered into the cultural lexicon recently. Bloch is someone whose temper is initially celebrated – on the soccer field, a tantrum from him is pivotal and expected, whereas outside, its the ramblings of an unstable fool with anger issues. He eventually recedes into self-destruction, where his own response to his impending mental collapse is to wreak havoc on his own, as a way of paying back the despair he’s experienced as a result of the humiliation he’s encountered over the years. Arthur Brauss is exceptional in The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, taking on the main character with a combination of wild vivacity, relentless charm and a hint of malice that initially just appears to be rugged friendliness, but eventually devolves into unbridled anger. Despite the title, there are only two brief scenes of sport being played, which serve as the bookends for the film, where the previously-adored player has gone from the field to the stadium, having experienced a considerable loss of his own humanity, which launches him into a period of self-loathing, that can only be remedied through drastic, indelible actions. The film itself is more of a morality tale than a film noir – even though the two are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The film itself is structured in a way that goes against many of the conventions that inspired it. Rather than following a coherent story that sees the main character experiencing the traditional “success-fall-redemption” structure, The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is constructed as a series of moments that occur in the days after his embarrassing loss. Filmed with glorious scope and precision by Robby Müller (who would go on to collaborate with Wenders for decades), the film is formed around different episodic sequences that all reveal something deeper about the main character, eventually converging into a deeply unsettling story of a man trying to navigate a world he just can’t understand all that well anymore, especially when a poor decision puts him on the wrong side of the law, where his previous meanderings that went in search of some meaning to life are replaced by moments of retreat from the law and the rest of society, who would be chagrined not only to discover what he did, but his reasons for doing so in the first place. Its a film that doesn’t reject its inherent despair, and while it is often extremely bleak, there’s an underlying optimism to this film that shows that second chances are possible, even when they aren’t particularly warranted. We see the world through Bloch’s eyes, and we can either relate to his hopelessly corrupted vision of a world that seems to be against him or only grow in our own humanity by seeing how someone who has grown so jaded with life views the small joys of existence with such vitriol.

The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick is a very unconventional film, and one that works the best when it is taken not as merely a coherent drama, but as a series of moments in the life of someone who has committed a heinous crime, and while he may not be facing any legal ramifications, being able to evade suspicion long enough to escape, this doesn’t mean he’s able to avoid facing the consequences, with his actions festering until he is on the precipice of insanity, slowly being destroyed by his own guilt. It is a beautifully-made film that looks at very disconcerting issues, always being profound without ever deviating from a simple underlying set of ideas. It is a strange and uncomfortable film that sees Wenders establishing himself as someone who would go on to make an imprint on arthouse cinema, and while it may not be as polished or intricate as his later masterpieces, there’s no denying that The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick hinted at something very promising, and stands as one of the most fascinating subversions of genre filmmaking of its era. Quiet but pulsating with meaning and a genuine sense of curiosity into the human condition, this is something profoundly moving and deeply compelling, which is difficult for a film that fashions itself as a deeply unsentimental foray into the roots of existence.