One of my biggest regrets when it comes to cinema is not having explored John Huston sooner – I only made my proper introduction to his work a couple of years ago, and with every new film I see from him, I am amazed to see what he was capable of doing – whether one of his formative works, or something occurring towards the end of his career, he had such a diverse career, touching on so many different genres and stories. Recently, I ventured into one of his later films, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which stands as one of his most interesting, if not also entirely beloved by audiences who appreciate the unique approach Huston took to the western genre, effortlessly bringing it into New Hollywood where it found a second life as a form of alternative storytelling. A bridging figure between two radically different ages of filmmaking, Huston found success throughout his career, and its difficult to not consider him one of the very best to ever work, because as this film demonstrates, there was very little Huston was unable to do, with The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean being amongst his finest achievements, and one of the most original western films of its era, a perfect midway point between the different iterations of the genre, it is a wonderful transitional piece that borrows heavily from different eras and genres, forming a compelling and thoroughly unique film that confirms Huston as one of his generation’s very best.

One of my biggest regrets when it comes to cinema is not having explored John Huston sooner – I only made my proper introduction to his work a couple of years ago, and with every new film I see from him, I am amazed to see what he was capable of doing – whether one of his formative works, or something occurring towards the end of his career, he had such a diverse career, touching on so many different genres and stories. Recently, I ventured into one of his later films, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which stands as one of his most interesting, if not also entirely beloved by audiences who appreciate the unique approach Huston took to the western genre, effortlessly bringing it into New Hollywood where it found a second life as a form of alternative storytelling. A bridging figure between two radically different ages of filmmaking, Huston found success throughout his career, and its difficult to not consider him one of the very best to ever work, because as this film demonstrates, there was very little Huston was unable to do, with The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean being amongst his finest achievements, and one of the most original western films of its era, a perfect midway point between the different iterations of the genre, it is a wonderful transitional piece that borrows heavily from different eras and genres, forming a compelling and thoroughly unique film that confirms Huston as one of his generation’s very best.

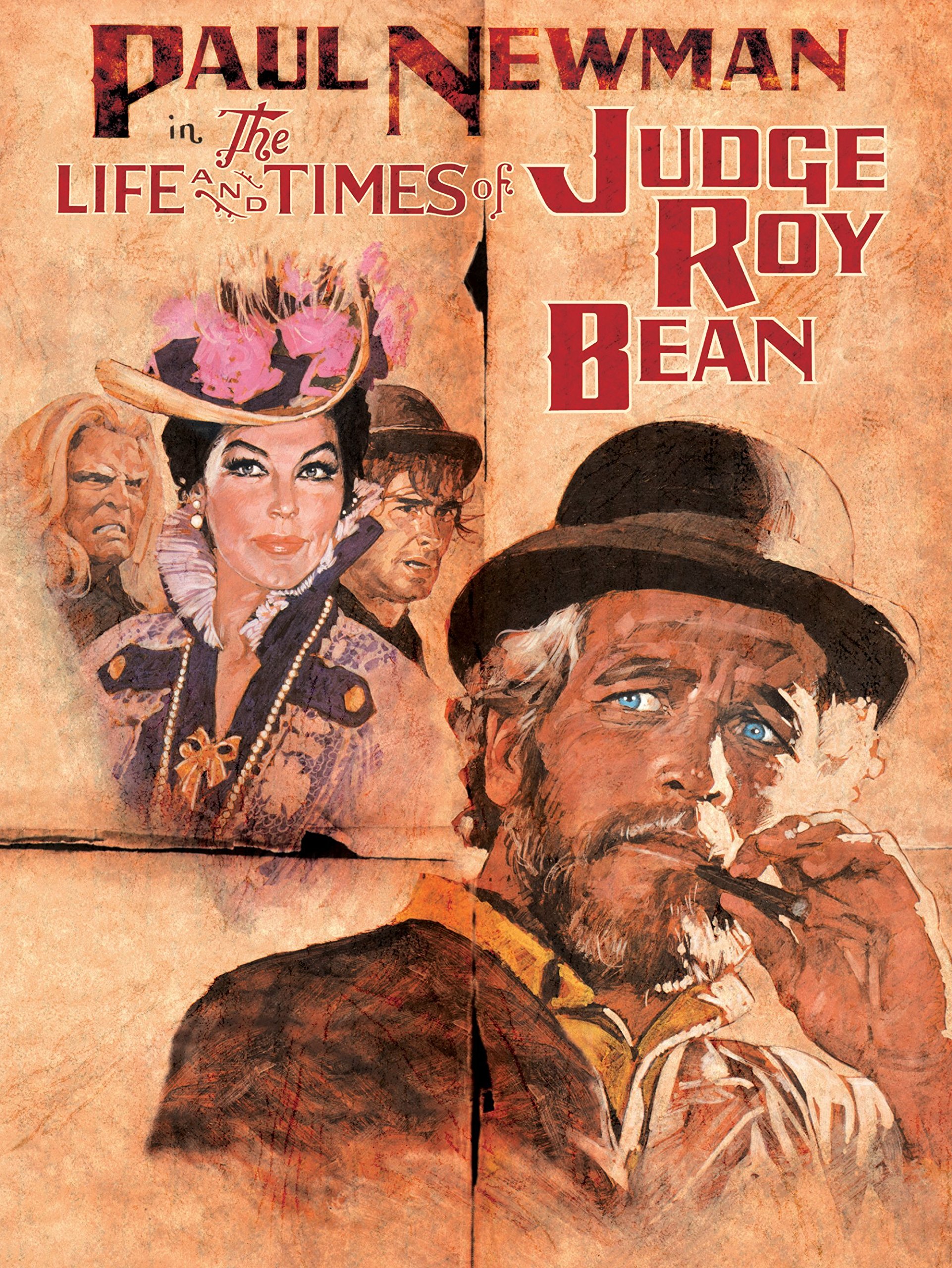

The film is a chronicle of the life of the titular character, Roy Bean (played by Paul Newman), a notorious outlaw who finds himself seeking a drink in a desert town somewhere in rural Texas, where nothing other than a whorehouse and a few shacks stand. He launches a one-man mutiny on the inhabitants after they try and kill him, and proclaims himself the embodiment of the law, taking on the title of “Judge” and seizing control over the region. As the years go on, Bean’s humble hamlet transforms into a bustling town, filled with people who gladly sit under the control of their harsh but benevolent leader, who may be all too willing to execute anyone who gets on the wrong side of him (earning a reputation as being a “hanging judge”), but is still intent on keeping the citizens of his small town safe and to never allow his jurisdiction to fall into debauchery or danger – he is constructing his ideal version of America, one with a simple but strict system on how to behave and live one’s life, based on his own understanding of the law. However, the world is constantly changing, and progress inevitably reaches the small town, with the archaic views of Bean being soon replaced by a more structured system of government that may reflect modern life but goes against the simplistic views of the town – but even when confronted with threats against his power and existence as an independent entity, Roy Bean proves himself to be someone who will never go down without a fight.

The concept of the revisionist western has become a fascinating area of cinematic discussion, but at the time of The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, it was still in its infancy, only having been properly explored for the first time less than a decade before. The film begins with the words “maybe this isn’t the way it was, its the way it should have been”, which is a simple disclaimer that not only allows Huston the independence to take liberties on the story but also sets the tone for the rest of the film. This is certainly not like any other western film made during the period, and while its not the only one intent on subverting tropes and utilizing a massively popular genre to convey a deeper message, it does so in a way that feels entirely unique. By taking the real-life figure of Roy Bean and placing him at the core of this film, which chronicles his various trials and tribulations, Huston and screenwriter John Milius are venturing deep into the core of the genre, making use of a set of conventions in a way that is refreshingly original and always riveting. There is something so remarkably different about this film – it lacks the mindless hopefulness of older westerns, but also the cold acidity of later films that used the format to comment on the crimes, both social and political, committed during the period. There’s an undercurrent here that builds into something both beautiful and meaningful, which is more than it initially promised, and exactly why it is such a surprising gem of a film.

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is obviously far more than just an ordinary western, using the genre only as a point to leap off into deeper cultural commentary. If we condense everything that this film tries to convey (and despite being an enthralling, captivating piece, it is undeniably dense and filled with a lot of underlying meaning), it is essentially just a film about progress. Set between two centuries, the film represents a changing world, where nothing is stable, and everything is in flux. We are presented with a simplified version of the American heartland, and we watch as the film follows a few decades in the life of this town and the man who runs it, demonstrating the constant battle between traditions and modernity, two seemingly irreconcilable forces that seem to be unable to come to some form of symbiotic agreement. It takes on an even deeper meaning when we consider how this was Huston, an artist who helped define the Golden Age of Hollywood, making a claim for a space in New Hollywood, where legends were respected but not consulted, let alone allowed to make films that fit into the era. There are certainly traces of the old guard throughout The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean – it is essentially a revolutionary social drama packaged as a traditional western film, which is precisely why it succeeds. Huston may have been the epitome of an older version of the film industry, but he was definitely never out of touch, and the most remarkable part of this film isn’t that Huston was able to make something so daring despite his status as one of cinema’s great stalwarts, but that he was also able to make it in such an authentic way.

A deeper reading of this film (and one that I want to explore on a second viewing, as it only became clear well into the film) is that The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is an allegory for America as a whole, with the titular character and his town representing the country. At the outset, Vinagroon is a small town that operates well enough, although it appears to lack much resources or structure, until Roy Bean arrives, takes it by force and apparently brings knowledge and honour to a place he perceived to be nothing but the location of debauchery and immorality. Over the years, it begins to grow and starts to thrive into an independent entity all on its own -change comes to the town, and eventually envelopes it, to the point where everything, including the person who seemingly built it up to this point, have to step away as the march of time, which waits for no one and dismisses all ideas of traditions, takes over. Roy Bean’s belief in his own infallibility, and his eventual decline and attempt to revive himself, means a lot more than just being the tale of an anti-hero defending what he believes is rightfully his. It is a very complex film, but one that doesn’t appear to be dense, but rather finds its intelligence in the more subtle moments, which was something that Huston made perfect use of throughout his career – the most meaningful statements are those that come at unexpected moments, rather than those that are heavy-handed or try to preach a certain idea.

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is also defined by its ensemble – the film spans several decades, and as a result, there are numerous characters that weave through the narrative, appearing at different points throughout the film, making an impact without ever overstaying their welcome. The only constant in the film is Paul Newman, who was at his peak here and was starting to enter into a new stage of his career, where he would begin to occupy a more mature role. This film occurs midway between the stages of his acting career, where he was still young enough to play a dashing hero, but also old enough to play a world-weary man who tries to overcome his bitterness to see the world through idealistic eyes once again. If there was any doubt that Newman could command the screen, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is the perfect example of him doing so – charismatic but complex, endearing but not without his moments of misanthropy, his Roy Bean is such a brilliant construction, and may not be his most well-known or beloved role, but is certainly one of his very best. The rest of the cast occur in much smaller capacities (everyone other than Newman is credited as “guest starring”), with highlights including Anthony Perkins as an empathetic preacher, Stacey Keach as a particularly feisty outlaw looking for a fight, Jacqueline Bisset as Bean’s equally-precarious daughter who has inherited her father’s taste for conflict, and Ned Beatty, the most consistent character actor of the 1970s. The cast is exceptional, and nearly everyone has moments of brilliance, contributing to the broad and fascinating anthropological tapestry Huston so brilliantly forms.

John Huston really made a beautiful film with The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which is so much more than just an ordinary western with a conflicted lead. It may appear to be just another run-of-the-mill historical film that takes a look at a time in American history that is of considerable interest to artists and audiences alike. However, once you are fully-immersed in Huston’s unique and uncompromising vision, you are taken on a thrilling journey that keeps the audience captivated throughout. The successes in the film lie in both the broader qualities – the acting is superb, the cinematography is stunning and the production design is simple but effective – as well as the more subtle elements, such as in the tone and the approach to the story. The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is filled with warmth and has a very clear heartfulness that compensates for the sometimes bleak story. The film finds the perfect balance between the haunting and the hopeful, infusing the film with a lot of humour (there are points where you could be convinced that this is a very subtle comedy), and an immense amount of melancholy that sees Huston drawing comparisons between the past and the present, showing how time and progress are will happen, and no matter how much anyone protests, whether a solitary individual or an entire social group, it is inevitable.

Poetic and poignant, there is an underlying sorrow beneath the film, but one that feels hopeful and optimistic at the same time. The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean is a nearly perfect film, a beautiful exercise in visual storytelling that only someone with the craftmanship and world-worn wisdom of John Huston could ever hope to compose, which he does with the same intimacy and minimalistic style that can be found in all of his best films, where the story and characters take preference over visual flair, and where there is always a deeper meaning underlying the plot, which usually tries to convey a much deeper meaning, and often succeeds wholeheartedly. There aren’t many films like The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, but there also weren’t many people like him, so it only seems fitting that a film loosely based on his life would be a daring, hilarious and heartfelt character study that never loses sight of the bigger issues, even if the most profound moments are the more subtle ones, where life itself is condensed into this terrific, subversive masterpiece.