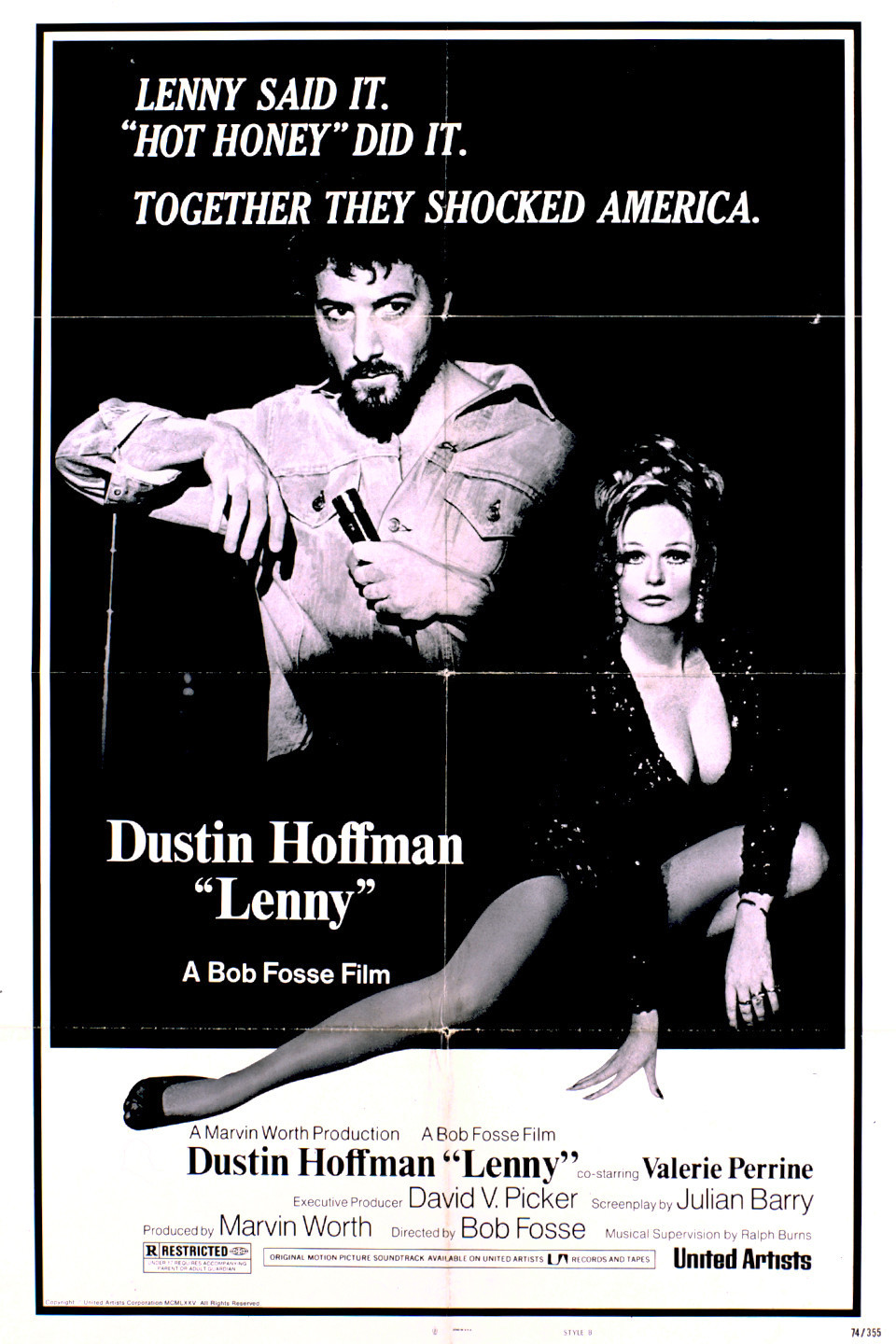

Lenny Bruce was an influential individual. Without him, there would not have been the likes of George Carlin, Richard Pryor or Bill Hicks, which in turn would mean comedy would have been very different, and probably far less important a force than it is now. Don’t let the preoccupation with jokes mislead you – comedy, for the most part, is a very serious business. Even when it isn’t merely being a welcome diversion from the insanity of reality, it is the medium through which some of the most profound and moving social statements can be conveyed, and where many comedians take advantage of the platform to comment on cultural issues in a way represented through the guise of humour, but are often bleak and haunting statements about the world we live in. This brand of comedy, which has often been compared to counterculture protesting, has its roots firmly within the career of Lenny Bruce, who may not have necessarily been the first comedian to take aim at society’s biggest flaws, but certainly was one of the most famous martyrs, a man who risked absolutely everything, including his freedom, to stand on stage and impart the truth as he saw it – without him and his defiance of the institutions that govern everyday life, the comedic landscape would not be quite the same. Bob Fosse understood this, which is why his biopic on Bruce, simply titled Lenny, is a fascinating character study, a deeply poignant drama about outrageous comedy that stirs emotions, provokes thoughts, and perhaps even changes a mind or two, as we venture into the trials and tribulations of arguably the most influential comedian of his era.

Lenny Bruce was an influential individual. Without him, there would not have been the likes of George Carlin, Richard Pryor or Bill Hicks, which in turn would mean comedy would have been very different, and probably far less important a force than it is now. Don’t let the preoccupation with jokes mislead you – comedy, for the most part, is a very serious business. Even when it isn’t merely being a welcome diversion from the insanity of reality, it is the medium through which some of the most profound and moving social statements can be conveyed, and where many comedians take advantage of the platform to comment on cultural issues in a way represented through the guise of humour, but are often bleak and haunting statements about the world we live in. This brand of comedy, which has often been compared to counterculture protesting, has its roots firmly within the career of Lenny Bruce, who may not have necessarily been the first comedian to take aim at society’s biggest flaws, but certainly was one of the most famous martyrs, a man who risked absolutely everything, including his freedom, to stand on stage and impart the truth as he saw it – without him and his defiance of the institutions that govern everyday life, the comedic landscape would not be quite the same. Bob Fosse understood this, which is why his biopic on Bruce, simply titled Lenny, is a fascinating character study, a deeply poignant drama about outrageous comedy that stirs emotions, provokes thoughts, and perhaps even changes a mind or two, as we venture into the trials and tribulations of arguably the most influential comedian of his era.

Bruce existed in a very difficult time, one that was not particularly welcoming to his world view, and where his style was completely against the perceived notions of decency, to the point where even just the use of certain words was enough to get him into legal trouble. Taking place between the late 1950s and early 1960s, Lenny follows the titular character as he rises from amateur comedian, who initially tried to make a name for himself through poor imitations of popular celebrities, as well as hackneyed jokes that incited vitriolic apathy rather than laughter, to the most outspoken counterculture critic of his generation. Showing his rise and decline (or rather, the plural, as he had several of both), we follow him as he starts to develop a following of some sort, winning just as many fans as he does enemies, who constantly perch themselves within arm’s reach of a man they saw less as a harmless comedian, and more of a social terrorist, someone whose discourse was profoundly dangerous, mainly because Bruce saw through all the disingenuity and falsehoods that were frequently spread by a government that, above anything else, relished in the self-control of the masses (the mid-1970s were a tumultuous time for the arts, and a great many films made during this era focus on themes relating to the broad socio-political climate at the time. Even something like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, as we saw recently, harnessed some form of underlying cultural critique in its approach). As we have seen, there is nothing quite as much of a nuisance to the government as someone who makes it his or her primary goal to expose the hypocrisy present within a certain society – and Lenny Bruce was one of those very people.

Making a film about Lenny Bruce was always going to be a challenge – despite being a comedian, there was absolutely nothing funny about his career. Someone far less obsessed with telling jokes and more concerned with revealing the truth, his stand-up work consisted of rambling monologues that exposed underlying hypocrisy, peppering in some elements of dark and subversive humour throughout in order to not only keep the audience entertained, but to engage with them in a way everyone understands – laughter is a universal language, and it is in those moments of hilarity that we can sometimes find the most affecting and powerful messages being conveyed. Bruce’s life was one misadventure to another, and he frequently found himself suffering at the hands of some entity – whether poverty, the law or himself, he was a man with profoundly rotten luck. Yet, he made the best of the situation throughout his career and perpetually made sure to build a legendary reputation from the scraps of misfortune that he constantly was left with during the course of his short but impactful professional endeavours. Bob Fosse was certainly an unexpected choice to helm a film about Lenny Bruce, considering he was a director known more for his work on Broadway, and with exuberant (but no less brilliant) works like Cabaret. It didn’t quite seem his style to make a gritty drama about a stand-up comedian. Yet, when you break it down, Fosse’s involvement makes perfect sense – Bruce was not just a comedian, but a boisterous performer, someone whose act was not just telling jokes or rambling on, but carefully-curated performance art – his constant arrests were clearly not accidental, but rather a ploy on behalf of the comedian to make sure he stayed in the public consciousness. There’s a certain nuance in the testimonies of someone who has been exposed to the brutality Bruce describes firsthand. When Lenny Bruce spoke, the audience listened, not because he merely imparts his opinion, but because he relays his own harrowing experiences, turning them into tools of social rebellion.

There was something so otherworldly about Dustin Hoffman at his peak – his work during the 1960s and 1970s was almost unprecedented, and established him as one of the most gifted actors of his generation. Lenny may not be the quintessential Hoffman performance, but when your career includes such masterful performances as those in Midnight Cowboy and The Graduate, that’s hardly a criticism. Taking on Bruce was going to be a monumental challenge, perhaps not in terms of embodying the comedian (the amount of footage of Bruce is not enough to form a full corpus of his mannerisms), but because this is a character very different from what Hoffman was used to playing – Bruce was an inherently defiant man, someone whose style and wit was almost entirely different from anything actors at that time, especially stars like Hoffman, could possibly convey without coming across as inauthentic. If anything, Bruce would’ve probably found the idea of a film about his life almost inappropriate. Yet, Hoffman rises to the challenge and delivers a powerful performance that is defined solely by two factors: the actor’s unquenchable ferocity, and his undying empathy. He had a seemingly insurmountable challenge ahead of him – he needed to play Bruce in his onstage persona, the social critic brimming with vitriol, but also the more sensitive side of the character – the hopeless romantic (and later husband), the father and most importantly, the man who is fighting for his right to not only say what he wants, but to allow anyone to say whatever they feel needs to be said. Hoffman’s performance is astoundingly good – he takes the elements of the role that would’ve been impingements to other actors and builds them into his most notable strengths, and while this is a relatively under-appreciated performance from the actor, it certainly is an achievement in itself.

Despite having made a name for himself as one of the greatest stage directors of all time, Fosse was also clearly a gifted film director, as evident in the few films he helmed. Not only is Lenny the outsider in his cinematic career in terms of the story, it is stylistically the director’s most interesting work – the film is presented as a series of moments in the life of Bruce, but structured in a way that is far more experimental than a conventional biographical film – the framing device used is a single performance Bruce gave towards the end of his career, where he relays the hypocrisies he has experienced. In between these moments, we are given glimpses into his personal life, as well as his journey towards fame, and his growth from a pathetic amateur to one of the great social critics of his era. This is further intercut with interviews conducted with characters who knew Bruce, presumably taking place after his death, with them reminiscing on his life and experiences from their own perspectives. It is in this complex structure that Fosse manages to make the most impact with his depiction of Bruce’s life – there are some moments of synchronicity that are extraordinarily meaningful – Bruce’s material often mirrors exactly what is being portrayed on screen, and often add nuance to what we are seeing before us. Consider the juxtaposition between his ex-wife’s heartwrenching testimony of their divorce and Bruce’s vulgarity-laden monologue about the experience of breaking up a family, or the intercutting between Bruce’s passionate monologue in front of the judge, begging for mercy, and his anger-fueled tirade that sees him viciously taking apart his court records on stage to an audience who did not quite understand what Bruce was doing. Fosse’s direction was masterful, and he compensates for the relatively simple style of the subject with a film that utilizes a compelling style that separates this from other similar films.

Lenny is a tough film – it is not something I would necessarily call a pleasant experience. At best, it is cold and unlikeable, at worst it is dull and unsentimental. Yet, it is a powerful film, one that takes a unique approach to a subject that does not make for simple storytelling. Fosse took an enormous risk in making an experimental drama about a comedian, and rather than making something upbeat and funny (which would not have been difficult, as despite his tendency towards apoplectic rage against the socio-political institutions, Bruce was a remarkably funny man, whose wit is as influential as his anger). It is a fascinating film, one that delves deeply into the mind of a man who saw the world in a very different way, and only wanted us to wake up to the injustices that are occurring all around us. Featuring Dustin Hoffman in his peak, delivering one of his most passionate and viciously brilliant performances, and working alongside someone like Bob Fosse, whose remarkable attention to detail and innovative directorial vision, make his collaboration with Hoffman absolutely astonishing. This is a unique film – it alternates between effortlessly cool, featuring an acid jazz score and brief touches of the French New Wave (particularly in the romance between Bruce and his soon-to-be bride), and the hopelessly bleak, showing a man who only wants to convey the truth, and being punished for it. It is by no means a perfect film, and the climax seems misplaced and rushed. However, it is a fascinating portrait of one of the great comedic voices of all time, and an individual whose pursuit of freedom more than warrants his reputation as one of the great artists of his generation, and someone whose influence continues to be seen even today.