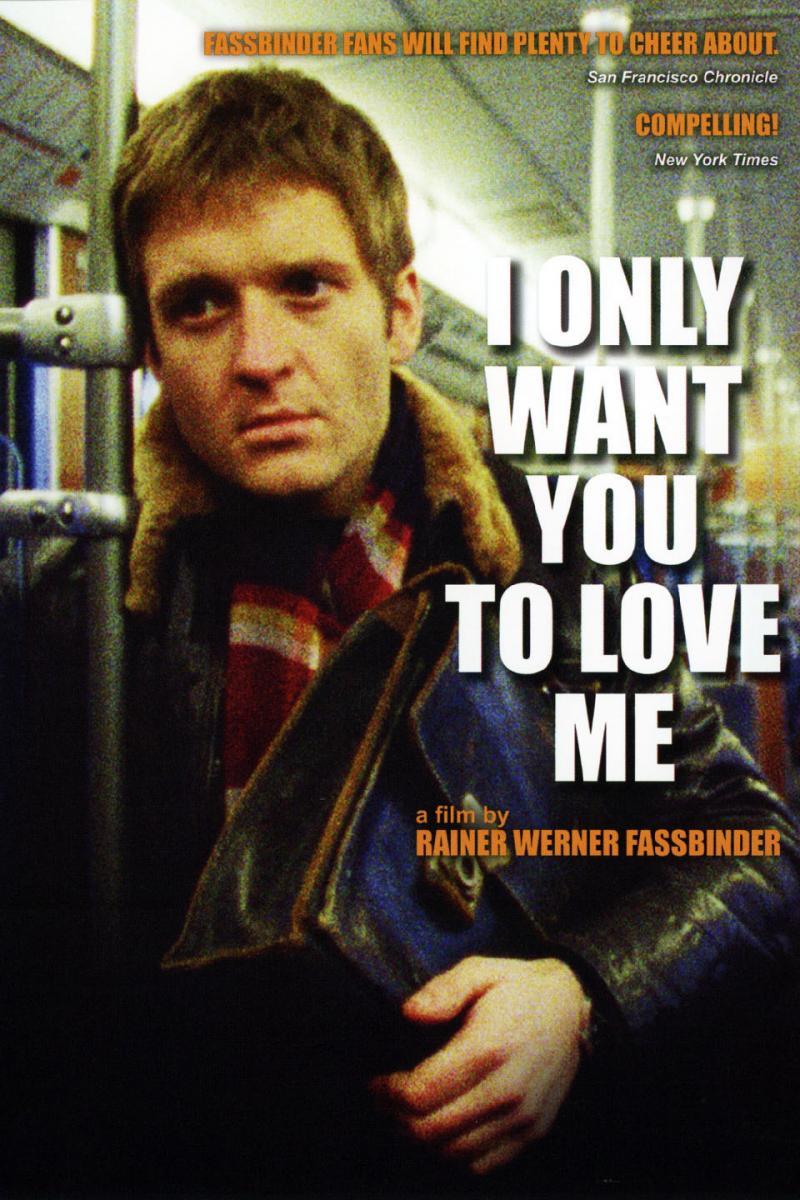

Like any given year during the peak of his filmmaking, 1976 was quite a busy year for Rainer Werner Fassbinder. This year, in particular, bears significance because three of his most notable films were all released then, each one of them extremely different in genre, story and even quality. Amongst the films he produced in this time are his very worst (the utterly revolting attempt at dark comedy in the aptly-titled Satan’s Brew), his most audacious (the chilling family drama Chinese Roulette), and the subject of this review, which is amongst the director’s best work and one of the year’s most extraordinary achievements. I Only Want You to Love Me (German: Ich will doch nur, daß ihr mich liebt) is an exceptional film that sees Fassbinder venturing into the realm of storytelling that he had the most aptitude for – social realism, psychological drama and cultural relations were all subjects that Fassbinder was always profoundly adept at, and this film, which was made for television and thus didn’t have the worldwide exposure that some of his more acclaimed films that received cinematic distribution did, stands as one of his most underrated works, a beautifully-composed drama about a single man trying his best to navigate a world filled with ungrateful, selfish people, including those who is closest to him. Fassbinder is one of the most ardent examples of a filmmaker soaring when they keep their work as simple as possible, and I Only Want You to Love Me is not particularly high-concept (despite having a structure that could’ve been seen as a lot more experimental than his other work), but it is effective precisely because it allows Fassbinder the space to tell a compelling story without needing to concern himself with external factors. It is straightforward, unpretentious filmmaking, and a masterful achievement from the director.

Like any given year during the peak of his filmmaking, 1976 was quite a busy year for Rainer Werner Fassbinder. This year, in particular, bears significance because three of his most notable films were all released then, each one of them extremely different in genre, story and even quality. Amongst the films he produced in this time are his very worst (the utterly revolting attempt at dark comedy in the aptly-titled Satan’s Brew), his most audacious (the chilling family drama Chinese Roulette), and the subject of this review, which is amongst the director’s best work and one of the year’s most extraordinary achievements. I Only Want You to Love Me (German: Ich will doch nur, daß ihr mich liebt) is an exceptional film that sees Fassbinder venturing into the realm of storytelling that he had the most aptitude for – social realism, psychological drama and cultural relations were all subjects that Fassbinder was always profoundly adept at, and this film, which was made for television and thus didn’t have the worldwide exposure that some of his more acclaimed films that received cinematic distribution did, stands as one of his most underrated works, a beautifully-composed drama about a single man trying his best to navigate a world filled with ungrateful, selfish people, including those who is closest to him. Fassbinder is one of the most ardent examples of a filmmaker soaring when they keep their work as simple as possible, and I Only Want You to Love Me is not particularly high-concept (despite having a structure that could’ve been seen as a lot more experimental than his other work), but it is effective precisely because it allows Fassbinder the space to tell a compelling story without needing to concern himself with external factors. It is straightforward, unpretentious filmmaking, and a masterful achievement from the director.

The film is focused on Peter Trepper (Vitus Zeplichal), an ordinary young man. He is unselfish and has an enormous heart, always striving to give everything he can to those around him. The problem is, the people in his life are profoundly ungrateful – he builds his parents (Alexander Allerson and Erni Mangold) a house, labouring for months over planning and constructing it all on his own, only to have them disregard his efforts and forget who built it for them a few weeks later. His wife, Erika (Elke Aberle) is loving but unsatisfied, longing for a better life than the one her husband, who she married on an impulse, seems to be able to provide her. Unfortunately, despite being an exceptionally good man, Peter is not skilled in anything other than construction, and even though he finds a good job and impresses his employers enough for them to ensure that he won’t be retrenched anytime soon, as well as giving him a raise in his wages every so often, he can’t provide everything that his wife and newborn son require. Over time, Peter grows disillusioned with the world – he is tired of the dismissal he gets from those who don’t recognize his efforts, and finds himself in existential despair when he realizes that he is trapped in a routine that is impossible to escape from, in a deadly cycle of overspending more than he can earn, only to satiate his wife and ensure that she doesn’t leave him. Ultimately, all that Peter wants is for his family to love him, which he finds is a lot more difficult to achieve considering how, despite his efforts, he is all too often disregarded.

There have been very many great performances in Fassbinder films – I can think of nearly a dozen extraordinary, iconoclastic portrayals throughout his storied career that stands as some of the greatest screen performances of their age. Vitus Zeplichal gives one of the very best from all of the ones I have seen, and the fact that this performance isn’t given the recognition it deserves is unfortunate, because what Zeplichal does here is unlike anything Fassbinder’s actors have been able to do – his performance in I Only Want You to Love Me is an exercise in subtlety, with absolutely every moment he is on screen being infested with quiet intensity and hopeless despair. His performance is very much internal, with the exception of the harrowing ending, and everything that goes on in Peter’s mind is portrayed so brilliantly through his ability to restrain his emotional expressions to the point where the joy, the sadness, the pain and the despair are so evident, but still so subtle. What he does with a single movement, or with the delivery of the most inconsequential line of dialogue, is astonishing. It isn’t a particularly conspicuous performance, but so much of the character’s likeability, and his position as being undeniably one of Fassbinder’s most sympathetic figures, is the result of Zeplichal’s spirited performance, where he manages to carry the film, interacting with Fassbinder’s screenplay in a way that he becomes the character, inhabiting his persona so effortlessly, we feel nothing but absolute empathy for his plight and sympathy for the fact that he is one of many people who struggle to make ends meet, despite his good-natured disposition and desire to always do what is right.

I Only Want You to Love Me is Fassbinder’s most compassionate film – it has the soulful delicacy and profound gentleness that we have seen in Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day, but the socially-charged thematic content of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul or In a Year of 13 Moons, which were predominantly realist films with underlying melodrama, only restricted by the limited budget and short production time that prevented them from becoming too gaudy. I’d even go so far as to categorize this film as being akin to Fox and His Friends insofar as the protagonist is a fundamentally good person who has a moment of sincere providence, but then encounters one misfortune after another, which leads to a harrowing decline that forces the main character into a situation of sheer desperation. I Only Want You to Love Me is a very delicate drama that doesn’t make many bold strides in terms of commenting on society in any exuberant way, but it still takes the form of a tragedy, whereby we are shown that the idea of good things coming to those who wait being unfortunately untrue in some instances, and that even someone with as good a heart as Peter can be subjected to the cruelty of the human spirit, where even his good intentions are wasted in favour of the self-serving desires of others.

The core of I Only Want You to Love Me really is Fassbinder expressing his own disillusioned view of modern living, whereby the world is run by money, and where individuals cannot get anywhere without material possession. It may be a taut saying, but if there was any simple way to describe the basic message of this film, its “money can’t buy me love” – and despite realizing this, Peter believes himself only worthy to provide for others – its certainly incredibly heartbreaking, because he is a deeply authentic and endearing character, and his plight is only worsened by the fact that he doesn’t deserve it. An argument can be made that he is the culprit for their financial insecurity, spending recklessly – but when you have grown up in a family that doesn’t appreciate anything and dismisses even the hardest efforts as minor duties, then its natural that someone would try and purchase affection. This is a heartbreaking tale of a man so intent on making those around him happy, he forgets entirely to ensure his own happiness, which manifests in a quiet rage that only becomes to fruition at the end, when his pent-up anger causes him to commit a heinous act that is uncharacteristic for a man who spent his entire life pleasing others. He was raised in a family that only gave him disapproval and indifference as a response to his earnest efforts, so it only makes sense that when it came time to do something for himself, it was an act of extreme violence.

Fassbinder reaches a new level of tenderness with I Only Want You to Love Me, taking a cue less from his own socially-charged melodramas and making something more aligned with Ken Loach and his contemporaries, with this film having the atmosphere of kitchen-sink realism rather than West German existential despair. All of the director’s notable directorial quirks are well-demonstrated throughout the film, but he is also tinkering with style and narrative, not experimenting to the point where it is notable, but making something a lot more nuanced than the often simplistic style he is known for. The combination of the more mature, earnest approach to the story, and the way in which Fassbinder presents it makes it a wholly unique experience, and one that is profoundly heartbreaking. The filmmaker is at his most bitingly misanthropic here, with his nihilistic outlook being predominant, supported by ardent attempts to find the happiness in such a bleak story. No matter how harrowing this film gets, there is always hope that Peter will get what he deserves eventually, because no good deed goes unrewarded, and even the final moment of the film, where a psychologist interviewing him (which is the framing device of the film) asks him “are you glad to be alive”, a sliver of hope still persists, whereby we feel that Peter will one day benefit from the same selfless kindness he so often demonstrated (only Fassbinder could make us feel utter sympathy for a convicted murderer). I Only Want You to Love Me is a beautiful, poetic and meaningful foray into the realm of character-driven drama that Fassbinder flourished in, and while this may not reach the impossibly high strides his other films tended to, this is certainly amongst his most underrated works, and a great example that beneath the madness, there was a truly empathetic, sincere artist who could represent humanity in so many different ways and never miss a single beat of sheer brilliance.