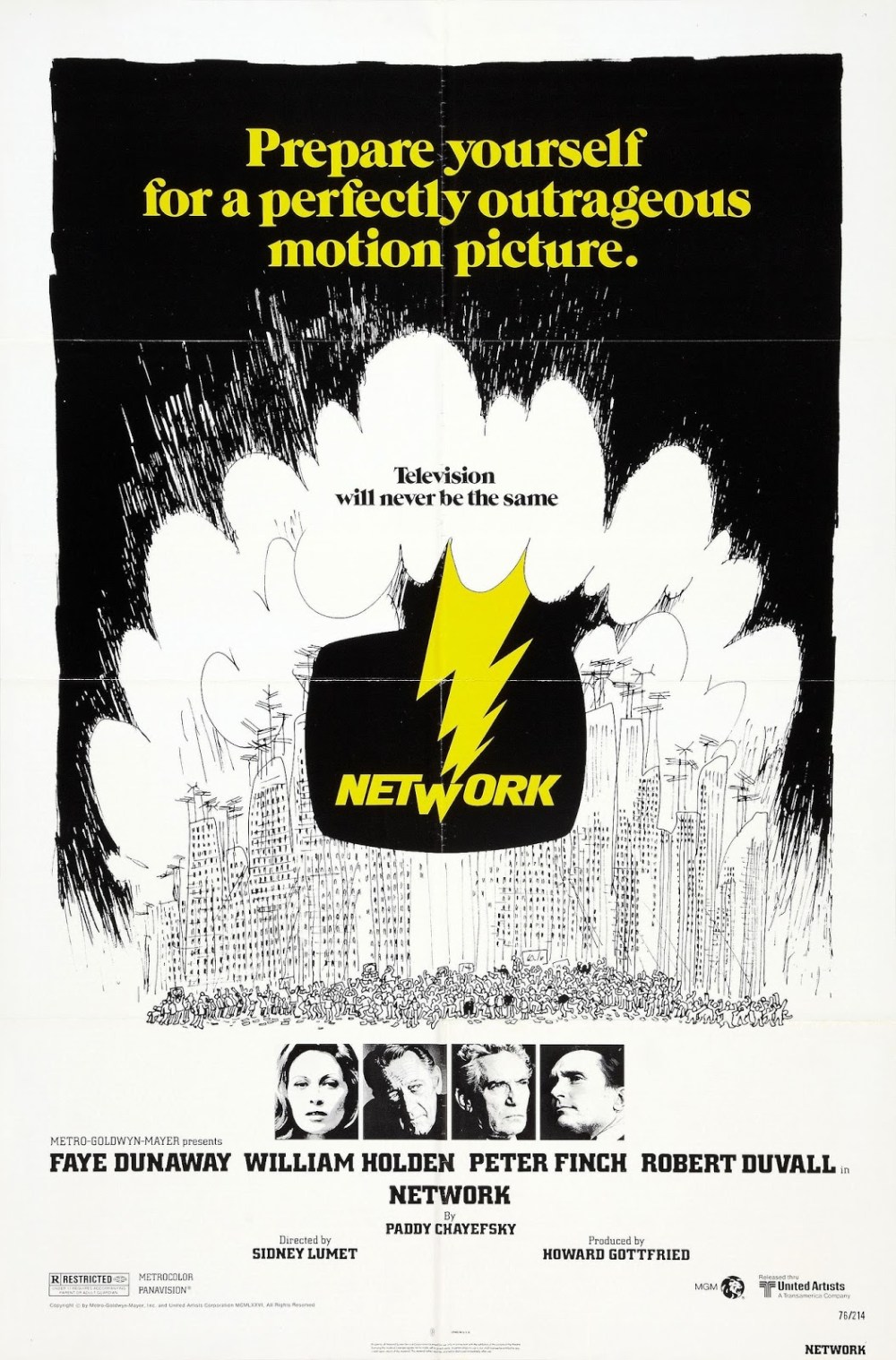

I first watched Network about a decade ago, when I initially sought it out after discovering that it is considered a seminal piece of New Hollywood filmmaking, and an essential example of satire. I thought it was a splendid film, but one that felt fundamentally cold and detached, and no matter how hard I tried, I just struggled to understand its appeal as anything other than a drama about the backstage machinations of a television network. I recently revisited the film for the first time since then, and somehow, in almost a moment of unprecedented clarity, I understood the impact of this film and realized precisely why this is such an iconic film. Naturally, one would assume that maturity played a part, as well as the rewatch revealing certain details that were missed the first time. But I’d argue that there was something about this film in relation to current affairs that just made it all the more striking. I went into Network expecting a well-crafted satire, not a harrowing, terrifying film that challenges the notion of truth and how the media distorts reality in a way that is profoundly and utterly bleak. Network takes on a new meaning in the modern age in the same way George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has unfortunately been repurposed as a handbook for living in the current age. This film may be quite beloved, and certainly has received its fair share of disdain from those vehemently opposed to its popularity (nearly every popular film gets some form of backlash, its a rite of passage for these kinds of New Hollywood films), but we can’t ignore the brilliance of this film, and Sidney Lumet, a director who made some of the most subversive crime films of the decade, being at the very peak of his career with his magnificent, horrifyingly film that takes the audience on an uncomfortable but powerful journey into the inhumane depths of reality television.

I first watched Network about a decade ago, when I initially sought it out after discovering that it is considered a seminal piece of New Hollywood filmmaking, and an essential example of satire. I thought it was a splendid film, but one that felt fundamentally cold and detached, and no matter how hard I tried, I just struggled to understand its appeal as anything other than a drama about the backstage machinations of a television network. I recently revisited the film for the first time since then, and somehow, in almost a moment of unprecedented clarity, I understood the impact of this film and realized precisely why this is such an iconic film. Naturally, one would assume that maturity played a part, as well as the rewatch revealing certain details that were missed the first time. But I’d argue that there was something about this film in relation to current affairs that just made it all the more striking. I went into Network expecting a well-crafted satire, not a harrowing, terrifying film that challenges the notion of truth and how the media distorts reality in a way that is profoundly and utterly bleak. Network takes on a new meaning in the modern age in the same way George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four has unfortunately been repurposed as a handbook for living in the current age. This film may be quite beloved, and certainly has received its fair share of disdain from those vehemently opposed to its popularity (nearly every popular film gets some form of backlash, its a rite of passage for these kinds of New Hollywood films), but we can’t ignore the brilliance of this film, and Sidney Lumet, a director who made some of the most subversive crime films of the decade, being at the very peak of his career with his magnificent, horrifyingly film that takes the audience on an uncomfortable but powerful journey into the inhumane depths of reality television.

Network is a film that is difficult to categorize – not because it defies genres or tries to reinvent cinematic conventions, but because its the mindset of the viewer that decides how this film is perceived. For some, this is a straightforward film about the backstage politics of a popular news network. For others, this is a darkly comical tale of the role of entertainment in our lives. Personally, while both of these are certainly true, the most accurate descriptor of this film is that of a profoundly terrifying piece of social commentary, which mixes reality with fiction in a way that feels almost inescapable and unquestionably disconcerting. There are so many moments in Network that are nauseating, to say the least, solely based on the way it relays the underlying message. The concept of truth is a profoundly important element of storytelling, especially for documentaries, or films that have their grounding in some form of reality. Network takes on an entirely new meaning in the current century, and while this kind of commentary has persisted since this film was made decades ago, there is something about the vision Paddy Chayefsky and Sidney Lumet present to us that resonates in unsettling ways considering the world we live in now. The biggest merit this film has is not that it only represented a declining media climate, but also predicted the corruption of truth and the rise of inaccuracy as a form of propaganda. The current age is defined by a form of media warfare, whereby news organizations are becoming increasingly deceptive in their methods, choosing sides and relaying more opinions than objective facts, which is unfortunately a product of a time when division is ultimately the goal of these major corporations that understand that fear and hysteria is the single most powerful entity in modern politics, and that harnessing fear for political and social purposes is the only way to make money through the news. It’s excessive and we can certainly find exceptions to this rule, but in the end, at the very core of these media empires resides a pulsating set of warped ambitions that motivates the peddling of hatred over the truth. This is the message conveyed by Network, with the various characters who weave through this film being indicative of this heartless industry.

In no uncertain terms, what makes Network so uncomfortable is that we don’t view this only as a film made during the 1970s as a response to a lot of political and social upheaval during that decade, but as the foresight to the only worsening conditions of the media that was to come. In no uncertain terms, Network becomes so much more disconcerting when looking at it in the age of contemporary politics, especially the cataclysm occurring in the United States, whereby the media seems to have forgotten the supposed neutrality of the news, rather pushing a certain agenda to the point where they aren’t reporting the news, they’re making it. In an age with figures like Rush Limbaugh and Alex Jones, we can’t look at someone like Howard Beale, whose mental instability and penchant for unhinged, rambling breakdowns are seen as entertainment, not as the unfortunate decline of a man who clearly needs help. Speaking the truth and “telling it like it is” is no longer what it was before: shock-jocks, anti-establishment politicians and controversial media figures are taking advantage of the public’s desire to hear what they want to hear. It is creating an echo chamber of manipulation and provocations along certain hot-button issues, relishing in the ability to divide in a time when unity is the only way these problems are going to be solved. The truth seems to be the enemy in modern times, and this is not a thinly-veiled attack on a certain system, but rather the media as a whole. Both conservative and liberal media are equally as guilty of peddling a certain subversive message disguised as the truth, which is, unfortunately, the state of affairs. The days of unbiased, neutral reporting is gone, and Network‘s biggest merit is the same as its biggest flaw: it has aged far too well because it represents the media in a way that is profoundly real and reflects the way news is reported nowadays, which is utterly terrifying.

Paddy Chayefsky was a writer who always had his grasp firmly on the pulse of the social and cultural zeitgeist – his work was always scathing, honest and relevant, and remain resonant to this very day, not only because they are fresh approaches to specific issues, but because he deconstructed reality in such a way, showing the way the world actually operated, which has not changed all that much since he was writing decades ago. Network is his masterwork, a bitingly funny satire about the way media corporations operate and how they are fundamentally nothing more than public forms of the mafia – each television station was in a fierce battle with its competitors, struggling for viewership and success, with all of them going to extraordinary lengths to ensure they were on top. The fictional network at the core of this film is Union Broadcasting System, a low-rated station that is struggling for relevance. Watching Network in 2019 is a very different experience to when this film was made when television was still in its heyday – cable television was not nearly as prestigious, and the internet had yet to even be conceived as a public entity, so the idea of streaming services was not even a distant thought yet. Twenty-four-hour news channels were also on the horizon, but not yet established. If anything, Network is a fascinating time capsule of a time when network television was dominant, with absolutely nothing else being nearly as powerful. The television set was a vital part of every suburban and urban household – it was the arbiter of entertainment, the harbour of thrills and the messenger of very serious messages, which were delivered with earnest sincerity and supposed neutrality by a trusted anchor. Network questions something in this regard: what if that goes wrong?

What happens when something goes wrong? This is the central question at the heart of Network, and the main impetus for the plot. Naturally, when a very public mental breakdown happens, the natural human response to is nurture that person by getting him or her the help they need, especially when its a public figure. One of the first key concepts of Network is that of celebrity – Howard Beale goes from being a trusted but somewhat boring figure to a significant entertainment figure. The abandonment of consistency in favour of lunacy is unfortunately not the basis for him seeking help, but rather being exploited more. The figure of Howard Beale is one that is profoundly tragic – as unhinged as he may be, he still possessed a certain quality that made him vulnerable and fragmented. Of course, naturally those around him don’t regard him as a person, but rather as a brand – and this sudden shift in his behaviour was the catalyst for extreme measures, namely that of rebranding him not as the image of consistency, but the exact opposite – his unpredictable nature, and clear volatile persona was far more entertaining, and audiences (which are not necessarily made out to be complicit, but are certainly not portrayed positively here either) enjoy these mad ramblings to the point where Beale’s newfound fame comes as a result of a complete disregard for him as a person and his own fragile mental state. Celebrity is something so many strive for, but the ramifications of being in the public eye are far more disturbing, and as this film demonstrates, being a well-known figure may bring wealth and influence, but it also has massively negative aspects as well, which can cause even more harm. The message of Network is that audiences, for the most part, don’t care about the figure as a person, but rather as an entity that serves to inform or entertain, and thus one’s status isn’t determined by their virtues, morals or beliefs, but whether or not they can bring in viewers, which is harrowing and unfortunately very much the truth.

If Network doesn’t make you feel any range of emotions – anger, despair, terror – then you’re not watching it right. It isn’t so much the film itself that carries these heavy meanings, but rather what it implies. The media landscape is so honestly portrayed here, it is beyond disconcerting, and when we consider that nothing much has changed, it only becomes more unsettling and certainly can trigger some form of existential crisis when this film makes the bold statement that even something supposedly as objective as the news could be constructed. Television has always been promoted as a direct portal between the viewer and the programming, with the concept of the existence of some intimacy between the two. Network looks at the ambigious grey area between them, the one that finds its homes in the boardrooms of large buildings and behind the scenes of familiar sets – this is where the truth is manufactured in a way that doesn’t hold the audience to any esteem, but rather serves to be a way of making money. The concept of ratings is at the core of the film, and during the very bleak ending, where Howard Beale is brutally gunned down on national television while commercials play around his dead body, all the narrator can say is that Howard Beale was “the first known instance of a man who was killed because he had lousy ratings” – and while this is obviously a heightened instance made for dramatic effect, it incites deep and often worrying thoughts about what other significant events that were perceived as factual were actually the product of scheming and planning by executives not looking to inform the audience, but rather to chase the elusive dollar through boosting their ratings. It’s anarchic, utterly brilliant filmmaking and the satire is so potent here, it almost becomes overwhelming.

Yet, even beyond its central message, Network is a remarkable film. Peter Finch occupies one of the four central roles, and he is terrific as Beale, a man who is having a very public breakdown, someone who is seeking help from the widest possible audience, but not receiving anything by apathetic applause and cheers from an audience who cannot harness enough self-awareness to even give a second thought to the fact that the man they perceive as some deranged jester may actually be in need of some assistance. Faye Dunaway has an opposing character, playing the vicious Diana Christensen, who is happy to exploit absolutely anyone for the sake of getting viewers – her ruthless, direct approach to programming may make her a profoundly influential figure, but is also demonstrates that she is someone who is only feeding the media epidemic, whereby nothing other than money matters. Robert Duvall has a similar role as the money-obsessed head of the network who is more than willing to go to any lengths to protect his reputation, that of his corporation and the sanctity of their financial gain from the insanity of their newest and most popular televisual attraction. Its William Holden as Max Schumacher that is one of the few people that possess some semblance of sympathy in this film – yet he is equally as guilty as everyone else, because even he is confronted by a very simple choice – help the man you ardently insist is your oldest and closest friend when he is clearly seeking help, or continue to aid and abet his exploitation for the sake of selfish gain. It becomes very clear that every character in this film is motivated by something far deeper – a carnal, lustful desire for money, fame and influence, and when that starts to impinge on the way we approach truth and objectivity, then we certainly have a problem.

Network is obviously not a film that has any shortage of literature written about it – this review certainly doesn’t say much that hasn’t been said already several times before. However, this is a film designed precisely to be discussed, and it would be so easy to launch into a much deeper analysis of this film. There is a certain intimidation that comes with reviewing a film like this that is so prominent and the subject of so much analysis – but at its core, this is a film that tells a story that resonates, but oddly should not: it isn’t right that this film is seen as being closer to fact than it is to fiction. It would be difficult to find anyone who watches this film to not feel the burden of reality weighing heavily on it, especially now in the age where “fake news” and “alternative facts” are not simply random words put together, but legitimate discourse spouted by influential people. Network is not a pleasant film – it is a dark comedy that uses its penchant for satirical humour in a way that is far more terrifying than it is amusing. It’s a drama that utilizes its tension to incite fear in the viewer and make us question everything we hold to be true. Paddy Chayefsky and Sidney Lumet were two artists who proved themselves to be significant voices in Hollywood during their respective careers, but Network remains arguably the magnum opus for both men, with their approach to this story being one that is profoundly honest, finding the truth in a landscape where we are made to believe every fact delivered with conviction and supported by alleged sources is supposed to be authentic. For this reason alone, Network should be exalted not only as a great satire but as a seminal piece of artistry that roots itself in our own world and provokes us to challenge everything, if we should dare and with utter caution, because the truth may not be particularly pleasant, and the realization that life is so inescapably corrupt, it may just make us mad as hell too – and are we going to take it anymore?

Darn good comparison to today’s media. This is the movie P.T. Anderson showed his cast before filming Magnolia. I think it was because of all the emotions Network stirs, as you observed. Great review. I need to see this again…

There is great bombast in this film. I was more taken with the quieter human moments.

I remember being terrified the first time I saw Beatrice Straight in Network. It has been nearly 40 years. I still remember gasping at the depth of pain a betrayal could inflict on a person with whom intimacy had been established for decades. I think her entire moment in the film is maybe five minutes and yet I wasn’t really able to concentrate after her appearance. I had to go back to see the film again.

Many films explore infidelity and the end of a marriage. Some do it better than others. During the 1970s, the feminist movement was changing our perspectives. Older women who remained committed to their marriages and their old fashioned sense of duty were pitied, even distained by many. I thought Paddy Chayefsky wrote a brilliant scene to give voice to those women who had devoted their lives to a belief in the sanctity of marriage and then had been silenced by a change in societal values. Straight’s rage was raw and clearly rose to the occasion.

This is an unforgettable performance.